Impacting a woman’s freedom to reproductive choices

Relevance

- GS Paper 2 Welfare schemes for vulnerable sections of the population by the Centre and States and the performance of these schemes.

- Mechanisms, laws, institutions and Bodies constituted for the protection and betterment of these vulnerable sections.

- Tags: #Foetus #Rights #WomanAutonomy #26weekPregnancy #MTPAct1971 #GS2 #UPSC

Why in the news?

- On October 16, the Supreme Court of India ruled on a case titled X vs Union of India.

- The case revolved around a woman seeking permission to terminate her 26-week-long pregnancy.

- The Court declined the woman’s plea to terminate her pregnancy, as it involved a “viable foetus.”

- The Supreme Court’s decision placed the rights of the foetus at a higher level than the rights of the pregnant woman to her privacy and dignity.

- This decision raised concerns about the balance between foetal rights and a woman’s autonomy over her body.

- The decision emphasized that the Court’s extraordinary powers should be reserved for cases falling within the specified scope of the Medical Termination of Pregnancy (MTP) Act of 1971.

Background to the Case

- The petitioner, identified as X, is a 27-year-old married woman with two children, the youngest being less than a year old.

- X sought termination of her pregnancy, which she discovered 20 weeks into her pregnancy due to lactational amenorrhea.

- The petitioner argued that when she finally had an ultrasound at 24 weeks, she was found to be pregnant.

- X’s Pleas: X made two key pleas in her case:

- Post-partum depression affecting her mental well-being

- Her family’s financial constraints as her husband was the sole earner.

Court’s Initial Hearings

- The Court, examining a medical board’s report from the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), initially ruled in favor of X.

- Justices Hima Kohli and B.V. Nagarathna held that continuing the pregnancy could have severe implications for X’s mental health.

- Union Government’s Challenge: Raised concerns about the viability of the foetus, leading to an impasse between the two judges.

- Disagreement Between Judges: Justice Kohli’s “judicial conscience” did not permit her to allow an abortion, while Justice Nagarathna emphasized the paramount importance of the woman’s choice.

- Justice Nagarathna argued that a foetus is dependent on the mother and cannot be recognized as an individual personality separate from the mother.

- Formation of a New Bench: Due to the impasse, a new Bench was constituted, presided over by the Chief Justice of India.

- New Medical Board Report:

- It confirmed the foetus’s viability and lack of abnormalities, as well as the safety of X’s medication during pregnancy.

- Since none of the MTP Act exemptions were met, the Court recalled its earlier order.

- Conflict with Privacy and Dignity Rights: The verdict contradicts the Court’s recent jurisprudence on the fundamental rights to privacy and dignity.

- In a previous case (X vs The Govt. of Delhi), the Court had emphasized the right to privacy and autonomy over one’s body and mind, including the freedom to make reproductive choices, particularly in cases of unwanted or incidental pregnancy.

- MTP Act as Enabling Legislation: When the statute’s provisions fall short, the Court should issue directions to further a woman’s right to choose, in line with the principle of human dignity.

- Inadequacies in the X vs Union of India Ruling: The ruling in X vs Union of India does not align with the idea of an enabling legislation or the protection of reproductive choices, as articulated in previous judgments.

- This ruling appears inconsistent with the Court’s previous decisions on privacy, dignity, and the right to make reproductive choices.

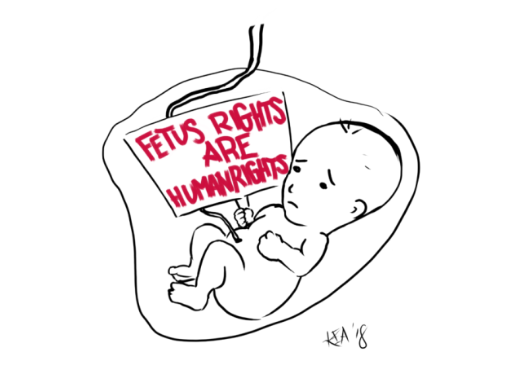

Foetuses and Rights

- Foetal Constitutional Rights: The X vs Union of India judgment implicitly suggests that foetuses possess constitutional rights. This contrasts with the established jurisprudence on abortion, which is founded on the premise that the Constitution does not confer personhood on foetuses.

- Constitutional Guarantees: Articles 14 and 21 of the Indian Constitution grant rights to equal protection and life to persons. The Constitution does not explicitly bestow personhood on foetuses.

- MTP Act and Personhood: The Act does not assert personhood for foetuses. If it did, it would contradict its own provisions that allow exceptions to the specified timelines when a pregnant woman’s life is directly and immediately threatened.

- Dependency of Foetus: Justice Nagarathna’s perspective emphasizes that, within the constitutional framework, a foetus is inherently dependent on the mother.

- Treating a foetus as a separate, distinct personality would entail granting it rights not conferred upon any other class of person under the Constitution.

- Primacy of a Woman’s Reproductive Choices: The X vs Union of India judgment potentially undermines a jurisprudence that prioritizes a woman’s freedom to make reproductive choices. This freedom is considered intrinsic to Articles 14 and 21 of the Constitution.

Viable foetus versus woman’s right

- The Supreme Court’s judgment in the X vs Union of India case implies that a woman’s right to choose is extinguished when a foetus becomes viable and capable of surviving outside the mother’s uterus, unless specific conditions under the MTP Act are met.

Criticism of court’s Judgement

- Failure to address fundamental questions related to the foetus:

- Does a foetus possess autonomous moral status.

- Does it have legal standing?

- Can it exercise constitutional rights?

- The judgment does not engage with these questions, which results in prioritizing foetal rights over a pregnant woman’s rights to privacy and dignity.

- Fails to examine whether the MTP Act is merely an enabling legislation or if it facilitates the exercise of a fundamental right.

- Fails to consider whether the Act’s exemptions represent a conferral of rights in themselves, leading to a lack of clarity regarding a woman’s ability to terminate her pregnancy outside the Act’s specified terms.

Potential Considerations

-

- The Court could have explored whether a woman’s right to make reproductive choices is fundamental and flows from the Constitution.

- By addressing this, the Court might have been more inclined to issue directions beyond the MTP Act’s boundaries.

|

Medical Termination of Pregnancy (MTP) Act, 1971 The Medical Termination of Pregnancy (MTP) Act, 1971 in India provides the legal framework for the termination of pregnancies in the country. The Act outlines the scope and conditions under which a pregnancy can be terminated. Pregnancy Termination Period

Grounds for Termination

Authorization

Consent

Confidentiality

The MTP Act was amended in 2021 to expand access to safe and legal abortion services. The key changes introduced by the amendment are as follows:

|

Source: The Hindu

Mains question

Discuss and analyze the implications of the X vs Union of India case on the intersection of reproductive rights, constitutional principles, and evolving jurisprudence in India.