MAURYAN EMPIRE

Introduction

The Maurya period commenced approximately in 321 BC and saw its decline by 185 BC. This era signified the inception of the first subcontinental empire and witnessed the formulation of innovative and enduring governance methodologies.

Sources to study Mauryan empire

- Archaeological Sources: Punch marked coins, Northern Black Polished Ware (NBPW), Wooden Palace of Chandragupta Maurya in Pataliputra, Ashokan inscriptions and Edicts, Junagarh Inscription of Rudradaman I.

- Literary Sources: “Indika” by Megasthenes, “Arthashastra” by Kautilya, Visakha Datta’s “Mudra Rakshasa“, Dharmashastra texts, Puranas, Buddhist Texts including Jataka Stories, Deepvamsa, Mahavamsa, Divyavadan.

IMPORTANT RULERS

Chandragupta Maurya

- He toppled the Nanda dynasty and established Maurya rule in 321 BC with the guidance of Chanakya (Kautilya).

- Greek historians refer to him as ‘Sandrakottus‘, a variant of Chandragupta.

- War and Conquest:

- He defeated the Greek prefects (military officials) left behind by Alexander.

- He also vanquished Seleucus, Alexander’s general, around 301 BC, expelling him from the Punjab region.

- In the peace treaty, Seleucus ceded eastern Afghanistan, Baluchistan, and territories west of the Indus to Chandragupta.

- Territorial Expansion:

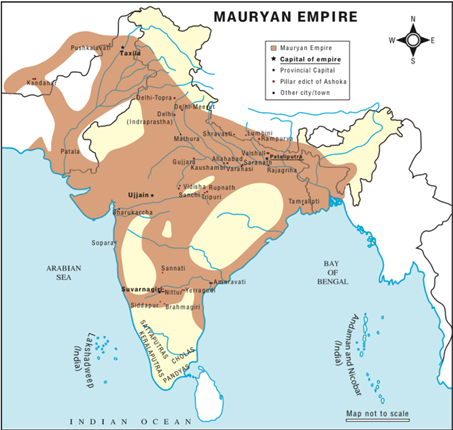

- He ruled over the entire subcontinent, including Bihar, parts of Orissa and Bengal, western and northwestern India, and the Deccan, excluding Kerala, Tamil Nadu, and parts of northeastern India.

- Greek writer Justin claimed Chandragupta conquered India with a vast army.

- Administration:

- Indica and the Arthashastra provide insights into the administration.

- The central government comprised about two dozen departments overseeing social and economic activities, especially near the capital.

- The empire was divided into provinces led by royal family members, further subdivided into smaller units.

- Army:

- The Mauryan military strength surpassed that of the Nandas.

- Pliny, a Roman writer, mentioned a massive army consisting of foot soldiers, cavalry, elephants, chariots, and a navy.

- The armed forces were managed by a board of 30 officers divided into six committees, each overseeing different military branches i.e. army, the cavalry, the elephants, the chariots, the navy, and transport.

- The Mauryan military strength surpassed that of the Nandas.

- Taxation:

- State-controlled agriculture on newly cultivated land involved cultivators and Sudra laborers, with taxes levied on the produce.

- Peasants were taxed from one-fourth to one-sixth of their produce, with additional charges for irrigation and tolls on commodities at town gates.

- The state monopolized mining, liquor sales, and arms manufacturing.

- Later Life:

- He likely renounced worldly life, spending his last years as an ascetic according to Jain tradition, in Chandragiri near Sravanabelagola, Karnataka.

| The Junagadh Inscription, carved during the reign of Rudradaman near Girnar in Gujarat and dating back to 130–150 CE, provides insights into:

● The extent of the Mauryan Empire, which had expanded as far west as Gujarat. ● It mentions Pushyagupta, the provincial governor (Rashtriya) serving under Emperor Chandragupta. ● It records the construction of Sudarshana Lake in the 4th century BC during the reign of Chandragupta Maurya. The lake’s completion occurred during the reign of Ashoka. ● Rudradaman I, a Shaka ruler, repaired the lake around 150 AD. |

Chanakya:

- Also known as Kautilya and Vishnugupta.

- Contemporary Jain and Buddhist texts do not mention him, but popular oral tradition attributes wisdom and genius to him.

- Authored the Arthashastra, a treatise on political strategy and governance.

- The play Mudrarakshasa by Visakhadatta, written during the Gupta period, narrates Chandragupta’s rise to power and the exploits of his chief advisor, Chanakya.

Megasthenes:

- Greek ambassador sent by Seleucus Nikator to the court of Chandragupta Maurya.

- Resided in the Mauryan capital of Pataliputra.

- Wrote Indica, detailing the physical, administrative, and cultural aspects of the subcontinent.

- He noted that famine was rare in India, and there was generally an abundance of nourishing food, even during wars.

- He mentioned seven castes in Mauryan society: artisans, farmers, warriors, philosophers, herders, magistrates, and council members.

Bindusara

- Succeeded his father, Chandragupta Maurya, in 297 BC.

- Continued his father’s tradition of close interaction with the Greek states of West Asia.

- Received counsel from Chanakya and other competent ministers.

- Died in 272 BC and was succeeded by his son Ashoka, despite Ashoka not being his chosen successor.

ASHOKA

- Ascended the throne four years later, in 268 BC, indicating a succession dispute between Bindusara’s sons.

- Converted to Hinayana Buddhism and adopted a pacifist policy.

- Referred to as Chakravartin in Buddhist texts.

- His reign marked political unification through one dharma, one language (Prakrit), and one script (Brahmi).

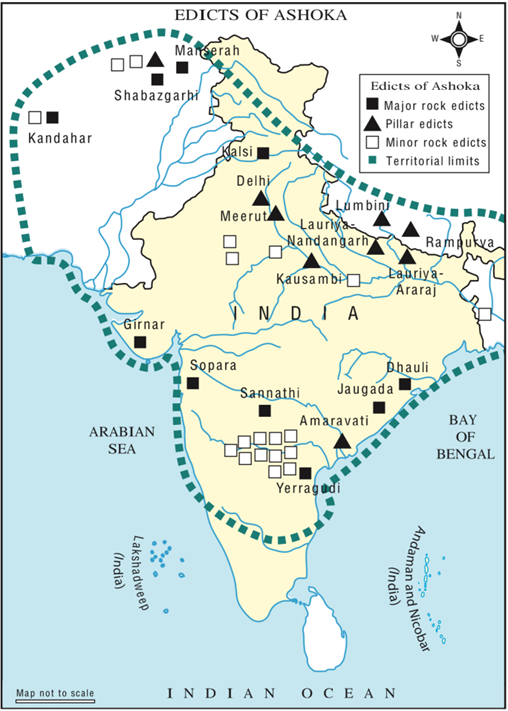

| Inscriptions: First Indian king to speak directly to the people through inscriptions.

● They were placed on ancient highways and provided details about the empire’s policies and extent, engraved on rocks, polished stone pillars, and caves across the Indian subcontinent and Kandahar in Afghanistan. ● Primarily written in Magadhi and Prakrit languages and Brahmi script, with Kandahar inscriptions in Greek and Aramaic and inscriptions in northwest Pakistan in Kharosthi script. ● Consist of 33 edicts, including 14 Major Rock Edicts, two Kalinga edicts, 7 Pillar Edicts, some Minor Rock Edicts, and a few Minor Pillar Inscriptions. ○ Major Rock Edicts extend from Kandahar in Afghanistan to Uttarakhand in the north, Gujarat and Maharashtra in the west, and Odisha in the east, and as far south as Karnataka and Kurnool district in Andhra Pradesh. ○ Minor pillar inscriptions found as far north as Nepal. ● A recurring theme in Ashoka’s edicts was the prevention of unnecessary slaughter of animals and the promotion of respect for all living beings. ● All edicts begin with a reference to the great king, Devanampiya (beloved of the gods) and Piyadassi (of pleasing looks), referring to Ashoka. ● James Prinsep deciphered Ashoka’s edicts in 1837, including Brahmi and Kharosthi scripts used in the earliest inscriptions and coins. Rumendei Pillar Inscription of Ashoka (Lumbini, Nepal): The inscription, written in the Brahmi script and Prakrit language, commemorates Ashoka’s visit to Lumbini, the birthplace of Shakyamuni Buddha, where he worshipped. |

Some Important Edicts

- Major Rock Edict 1: Prohibition of animal sacrifice and establishment of holidays during festive gatherings.

- Major Rock Edict 2: State responsibility for providing medical care; orders to set up hospitals for humans and animals.

- Major Rock Edict 3: Instructions for officials like Yuktas and Pradesikas to tour every five years to educate people about dhamma.

- Major Rock Edict 6: King’s desire to stay informed about the condition of the people.

- Major Rock Edicts 7 and 12: Advocacy for the coexistence of all religions and honoring ascetics of various faiths.

- Major Rock Edict 13: Mentions the war with Kalinga and promotes conquest through Dhamma instead of war.

- Kalinga Rock Edict 1: Officials urged to recognize their responsibilities and ensure impartiality and justice; periodic inspections to verify compliance.

- Maski Edict: Mentions Ashoka’s inscriptions being carved under the title ‘Devanampiya’.

- Major Rock Edict at Dhauli, Odisha

- Major Rock Edict at Jaugada, Odisha

- Major Rock Edict at Erragudi, Andhra Pradesh

- Major Rock Edict at Kalsi, Uttarakhand

Kalinga War

| The Kalinga War was a punitive campaign against Kalinga, which had seceded from the Magadha Empire. (Hathigumpha inscription speaks of Kalinga as a part of the Nanda Empire).

Effects of War on Ashoka: ● The brutality of the war deeply affected Ashoka, prompting a shift from physical conquest (Bherighosha) to cultural influence and the promotion of dharma (Dhammaghosha). ● He sought to ideologically conquer foreign territories through welfare measures for both humans and animals, refraining from further military campaigns. ○ Post-Kalinga war, despite ample resources, he abstained from engaging in further military conflicts. ○ He dispatched emissaries of peace to Greek kingdoms situated in Western Asia and Greece. ● Despite his pacifist approach, Ashoka retained the army and maintained control over the acquired territory of Kalinga. ● He pursued a policy of peace, non-aggression, and cultural conquest, unprecedented in Indian history at the time. |

Religious Policy

- Ashoka adopted a tolerant religious policy, refraining from imposing Buddhism on his subjects and making donations to non-Buddhist and anti-Buddhist sects, such as the Ajivika sects who received the Barabar caves.

- His visits to Buddhist shrines, termed Dharmayatras in inscriptions, underscored his commitment to Buddhism.

- He convened the Third Buddhist Sangha (council) in 250 BC in Pataliputra, aimed at expanding Buddhism’s reach through missionary activities.

- A fundamental result of the sangha was the extension of Buddhism’s influence to other regions through the dispatch of missionaries.

- Mauryan society saw harmonious coexistence among various religions, castes, and communities.

Missionary Activities:

- Ashoka dispatched missionaries to regions like Sri Lanka, Burma, and Central Asia.

- His children, Mahinda and Sanghamitta, were sent to Sri Lanka to propagate Buddhism, bringing along a branch of the original Bodhi tree.

- Brahmi inscriptions from the 2nd and 1st centuries BC attest to Ashoka’s missionary efforts in Sri Lanka.

Ashoka’s Administration:

- Ashoka adopted a paternalistic approach to kingship, viewing his subjects as his children.

- He propagated the principle of Dhamma and appointed officers (Rajukas) for administering justice and Dharma-mahamatras for promoting dharma among various social groups.

- He prohibited the killing of certain birds and animals and banned animal slaughter in the capital.

- His Dhamma aimed to maintain social order, emphasizing obedience to parents, respect for Brahmanas and Buddhist monks, and compassion towards slaves and servants.

- He maintained that people who behaved virtuously would attain heaven but did not explicitly mention nirvana, which constitutes the ultimate goal of Buddhist teachings.

- To prevent oppressive rule, Ashoka introduced the rotation of officers in regions like Tosali, Ujjain, and Taxila.

| Contemporary Rulers of Ashoka with whom he had Exchanged Missions

● Antiochus II Theos of Syria (260-246 BC), the grandson of Seleucus Nikator. ● Ptolemy III Philadelphus of Egypt (285–247 BC). ● Antigonus Gonatus of Macedonia (276–239 BC). ● Magas of Cyrene. ● Alexander of Epirus. |

After Ashoka’s death in 231 BC, the Mauryan Empire gradually declined and eventually collapsed. Pushyamitra Sunga, a Mauryan general, assassinated the last Mauryan king, Brihadratha, and seized the throne of Pataliputra, marking the end of the Mauryan dynasty.

Causes of Decline:

- Brahmanical Reaction: The anti-sacrifice stance of Ashoka and the rise of Buddhism resulted in a decline in patronage for Brahmins, who traditionally received gifts during sacrifices.

- Provincial Oppression: Misrule and oppressive governance in provinces, such as Taxila under Dushtamatyas during Bindusara’s reign, led to widespread discontent and revolts among the populace.

- Financial Strain: The maintenance of a vast army, bureaucratic apparatus, and generous grants to Buddhist monks imposed a significant financial burden on the empire.

- Neglect of Frontier Defense: Ashoka’s emphasis on missionary activities diverted attention away from protecting the northwest frontier, leaving the region vulnerable to external threats and invasions.

- Rise of New Kingdoms: Economic advancement and the spread of material culture facilitated the emergence of new kingdoms, challenging the centralized authority of the Mauryan Empire and contributing to its decline.

MAURYAN ADMINISTRATION

Brahmanical law Influences books and stresses that kings should adhere to Dharmasastras and local customs.

- Kautilya referred to the king as Dharmapravartaka (promulgator of social order), emphasizing the role of the king in promoting dharma during periods of social order disruption

- Ashoka affirmed the supremacy of royal orders in his inscriptions, underscoring the authority of the king’s decrees.

Central Administration

- The capital region of Pataliputra was under direct administration, while the rest of the empire was divided into four provinces situated at Suvarnagiri (near Kurnool in Andhra Pradesh), Ujjain (Avanti, Malwa), Taxila in the northwest, and Tosali in Odisha in the southeast.

- The administration featured an extensive bureaucracy, with each department employing a large staff of superintendents and subordinate officers connected to both central and local governments.

- The king led the administration, aided by a council of ministers, a priest (purohita), and secretaries known as mahamatriyas.

- An espionage system was established to gather intelligence and oversee officers;

- the Arthashastra recommends spies to work in disguise.

- Hierarchy and Salaries:

- Important officials known as ‘tirthas’ received salaries in cash.

- However, significant disparities existed in salaries, with high-ranking functionaries like ministers (Mantrin), high priests (Purohita), commanders-in-chief (Senapati), and crown princes (Yuvaraja) earning as much as 48,000 panas, while lower-ranking officers received as little as 60 panas or even 10 to 20 panas. (where Pana equals three-fourths of a tola.)

Provincial Administration:

- Provinces were overseen by governors, often members of the royal family, appointed by the central administration.

- Each province replicated the structure of the Mauryan state in terms of revenue collection, judicial administration, and bureaucracy, aiming to establish a uniform system of governance across the empire.

| Kautilya’s Saptanga Theory comprises seven essential elements

● Svamin (The King): The central figure and ruler of the state. ● Durg (Fortified Capital): The stronghold and administrative center of the kingdom. ● Janapada (Territory and Population): The land and its inhabitants, constituting the kingdom’s domain. ● Danda/Bala (Army or Force): The military strength and power of the state. ● Amatya (The Secretary): Officials responsible for advising and assisting the king in governance. ● Kosha (The Treasury): The state’s financial resources and wealth. ● Mitra (Ally): External alliances and diplomatic relationships with other states or powers. |

District and Village Administration

- District Administration: Each district was supervised by a Sthanika, while Gopas oversaw groups of five to ten villages.

- Village Autonomy: Villages enjoyed semi-autonomy and were governed by a Gramani appointed by the central government, along with a council of village elders.

- Urban Administration: Urban areas were managed by a

Judicial Administration

- Courts were established in major towns, with two types of courts:

- Dharmasthiya Courts: These dealt with civil law matters such as marriage and inheritance, presided over by three judges and three Amatyas (secretaries) knowledgeable in sacred laws.

- Kantakasodhana (removal of thorns) Courts: These were responsible for addressing anti-social elements and crimes, functioning akin to modern police. They were presided over by three judges and three Amatyas, with support from a network of spies.

- Punishments for crimes were often severe, reflecting the strict legal framework of the Mauryan administration.

Important Officers

| ● Sitadhyaksha: Overseer of agriculture.

● Bandhanagaradhyaksha: In charge of the jail. ● Pautavadhyaksha: Superintendent of weights and measures. ● Panyadhyaksha: Responsible for trade and commerce. ● Lohadhyaksha and Sauvarnika: Supervised goods manufactured in the centers. ● Dandapala: Head of the police force. ● Nava Adhyaksha: Superintendent of ships. ● Sulkaadhyaksha: Collector of tolls. ● Annapala: Head of the Food Grains Department. ● Durgapal: Head of the Royal Fort. ● Koshadhyaksha: Treasury officer. ● Akaradhyaksha: Mining officer. ● Nayaka: City security chief. ● Vyabharika: Chief judge. ● Karmantika: Head of industries and factories. ● Ayudhagaradhyaksha: Oversaw the production and maintenance of armaments. ● Swarn Adhyaksha: Officer of the Gold Department. ● Kupyadhyaksha: Officer of the forest department. |

Economy

The Mauryan economy had progressed beyond mere subsistence farming to a more sophisticated level characterized by commercial craft production.

- The state played a significant role in regulating economic activities through appointed superintendents (Adhyakshas), who oversaw agriculture, trade, crafts, mining, and other economic sectors.

Revenue Sources

- The state derived revenue from various sources:

- Control over agricultural production and trade.

- Imposition of additional taxes such as customs duties, tolls on commerce, land taxes (Bhaga), taxes on irrigation (if provided by the state), urban property taxes, and earnings from coinage.

- Monopoly over resources including crown lands (Sita-revenue), forests, mines, and salt production.

Taxation System

The Mauryan Empire introduced a sophisticated taxation system, focusing on revenue assessment and collection.

- A collector-general known as Samaharta oversaw revenue collection and supervised various revenue sources such as provinces, fortified towns, mines, forests, and trade routes.

- The Samaharta was responsible for assessing revenue across provinces and overseeing the state treasury and storehouses. Additionally, a chief custodian known as Sannidhata managed the state treasury.

- Taxes were collected both in cash and in kind.

- Rural storehouses functioned as famine relief during times of scarcity.

Currency and Market Exchange

- The Mauryan Empire adopted a uniform currency system, which facilitated market exchange across different regions of the empire.

- The imperial currency consisted of punch-marked silver coins known as Pana. These coins aided in tax collection and were used for payments to government officials.

- Silver coins, known as Karshpana, were also prevalent in Mauryan economy.

- However, they did not carry any specific symbols associated with Mauryan kings and were not issued by a central authority.

- Pana and its sub-divisions were the most commonly used currencies in the Mauryan Empire, facilitating economic transactions and trade exchanges.

Agriculture

- It accounted for the highest share in total state revenue and

- The fertile soil of India allowed for the cultivation of various crops.

- Megasthenes mentions the cultivation of food grains along with commercial crops like sugarcane and cotton. He also refers to unique crops such as a reed that produced honey (sugarcane) and a tree that yielded wool (cotton).

- The state played a crucial role in agriculture by providing irrigation facilities and managing water distribution.

- Officials, as mentioned by Megasthenes, monitored land measurement and inspected water channels to ensure efficient water distribution, similar to practices in Egypt.

- The Arthashastra documents the emergence of slave labor in agriculture during this era, with state-run farms employing slaves and hired workers.

- Additionally, war captives from the Kalinga War were utilized for agricultural labor.

- The labor force, consisting of slaves and hired workers, was provided by dasa-karmakaras.

- According to Arthashastra, if a child is born to a female slave by her master, both the child and its mother are to be immediately recognized as free.

- Furthermore, if a son born to a female slave was fathered by her master, the son would be entitled to the legal status of the master’s son.

- However, Megasthenes did not observe the existence of slaves in India.

Crafts and goods

- Spinning and weaving, particularly of cotton fabrics, emerged as the second most significant occupation after agriculture.

- The Arthashastra highlights regions known for producing distinctive and specialized fabric varieties, such as Kasi (Benares), Vanga (Bengal), Kamarupa (Assam), and Madurai, among others.

- Royalty and members of the royal court adorned clothes adorned with gold and silver embroidery, while silk, often referred to as Chinese silk, denoted extensive trade within the Mauryan Empire.

- Metalworking involved the utilization of iron, copper, and other metals.

- Iron smelting experienced notable technological advancements after around 500 BC, enabling smelting in high-temperature furnaces.

- Woodworking encompassed shipbuilding, cart and chariot construction, and house-building.

- Luxury goods production included gold and silver articles, jewelry, perfumes, and carved ivory.

- Craftsmanship constituted urban-based hereditary occupations, with sons typically following in their fathers’ footsteps. While craftsmen primarily operated independently, royal workshops also existed.

- Each craft was overseen by a head called Pamukha (pramukha or leader) and a Jettha (jyeshtha or elder) and organized into a Seni (sreni or guild) to ensure institutional identity, transcending individual craft production.

- Disputes between Srenis were settled by a Mahasetthi.

Trade

- Trade operated within a hierarchy of markets, including village markets, inter-village and town markets within districts, and across cities and kingdoms.

- Transportation of goods:

- In northern India, rivers in the Gangetic plains served as crucial transportation routes for goods.

- Overland roads facilitated the transport of goods further west and connected cities and markets in the southeast and southwest.

- These roads passed through towns such as Vidisha and Ujjain, linking various regions for trade and commerce.

- Merchant groups traveled in caravans for security, led by a caravan leader known as Mahasarthavaha, especially for long-distance overland trade.

- Urban markets and craftsmen were monitored and regulated to prevent fraud.

- Overseas trade with countries like Sri Lanka, Burma, and the Malay Archipelago involved relatively small ships, as evidenced by Buddhist Jataka tales recounting merchants’ long voyages.

- The Arthasastra catalogued agricultural and manufactured goods traded in both internal and foreign trade.

- Greek sources corroborate trade links with the west, particularly with Greek states like Egypt, exporting commodities such as indigo, ivory, tortoise shell, pearls, perfumes, and rare woods.

Spread of Material Culture

- The emergence of a new material culture was evident in the widespread adoption of iron, punch-marked coins, Northern Black Polished Ware pottery, burnt bricks, and ring wells, particularly in northeastern India.

- The utilization of soak pits and ring wells enabled settlements to move away from the river, a phenomenon initially observed under the Mauryas and later spreading to other regions within the empire.

- These developments fostered the proliferation of towns across various parts of the empire.

- Arrian, a Greek writer, documented the existence of multiple cities during this period, providing valuable insights into the urban landscape of the time.

- New settlements were founded with the assistance of cultivators (Vaisyas) and Sudra laborers, who were relocated from overpopulated regions to cultivate untamed land.

- These settlers received tax exemptions and were provided with cattle, seeds, and financial support to facilitate their agricultural endeavors.

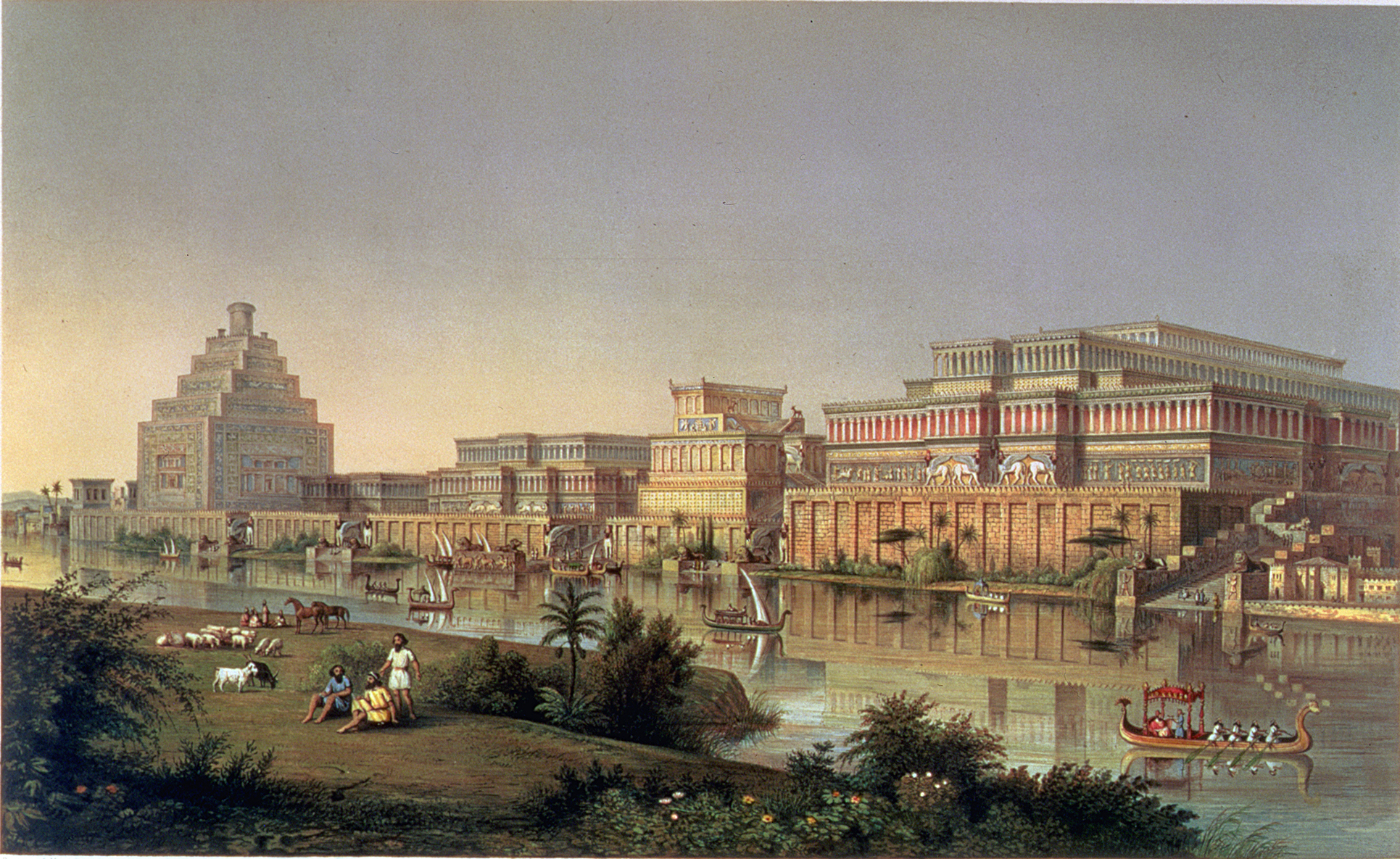

| Pataliputra, a sizable and affluent city, was situated at the confluence of the Ganga and Son rivers.

● The city boasted numerous grand palaces and supported a large population. ● City administration comprised six committees, each consisting of five members, responsible for tasks such as sanitation, care of foreigners, birth and death registration, and regulation of weights and measures. ● Monumental architecture adorned Pataliputra, including the construction of many-pillared halls commissioned under Ashoka’s reign. ● Megasthenes noted the presence of wooden structures in Pataliputra and likened its splendor to the capital of Iran. |

Art and Culture

- The Mauryas introduced extensive stone masonry, marking a significant development in architectural techniques.

- Stonework, including carving and polishing, became a highly refined craft, evident in stone sculptures found at the stupa in Sanchi and the use of finely polished Chunar stone for Ashoka’s Pillars.

- Discoveries such as fragments of stone pillars and stumps uncovered at Kumrhar (Patna) indicate the presence of an 80-pillared hall.

- The polished stone pillars exhibited a striking resemblance to Northern Black Polished Ware pottery. Each pillar was crafted from a single sandstone piece, with its capital seamlessly joined with the pillar on top.

Literature

- Much of the literature and art from this period have not endured through time.

- Buddhist and Jain texts were predominantly composed in

- Sanskrit language and literature saw enrichment through the works of Panini (circa 500 BC) and Katyayana (a contemporary of the Nandas who wrote a commentary on Panini’s work).

- The Arthashastra documents various performing arts of the era, encompassing music, bards, dance, and theatre.

- Sculptures found in Sanchi depict pictorial representations of cities, showcasing royal processions and urban landscapes.

UPSC PREVIOUS YEAR QUESTIONS

1. Who of the following had first deciphered the edicts of Emperor Ashoka? [UPSC CSE 2016]

1. Georg Bilhler

2. James Prinsep

3. Max Muller

4. William Jones

2. Consider the following pairs: [UPSC CSE 2022]

Site of major rock edicts Ashoka’s – Location in the State of

1) Dhauli – Odisha

2) Erragudi – Andhra Pradesh

3) Jaugada – Madhya Pradesh

4) Kalsi – Karnataka

How many pairs given above are correctly matched?

1. Only one pair

2. Only two pairs

3. Only three pairs

4. All four pairs

3. Who among the following rulers advised his subjects through this inscription? [UPSC CSE 2020]

“Whosoever praises his religious sect or blames other sects out of excessive devotion to his own sect, with the view of glorifying his own sect, he rather injures his own sect very severely.”

(a) Ashoka

(b) Samudragupta

(c) Harshavardhana

(d) Krishnadeva Raya

4. According to Kautilya’s Arthashastra, which of the following are correct? [UPSC CSE 2022]

1) A person could be a slave as a result of a judicial punishment.

2) If a female slave bore her master a son, she was legally free.

3) If a son born to a female slave was fathered by her master, the son was entitled to the legal status of the master’s son.

Which of the statements given above are correct?

(a) 1 and 2 only

(b) 2 and 3 only

(c) 1 and 3 only

(d) 1, 2 and 3

5. In which of the following relief sculpture inscriptions is ‘Ranyo Ashoka’ (King Ashoka) mentioned along with the stone portrait of Ashoka ? [UPSC CSE 2019]

1. Kanganahalli

2. Sanchi

3. Shahbazgarhi

4. Sohgaura

| IMPORTANT FACTS RELATED TO THE CHAPTER

● Mudrarakshasa, authored by Vishakhadatta, offers insights into the reign of Chandragupta Maurya. Dhundiraja wrote a commentary on this drama. Chandragupta is depicted as the son of Nandraja and referred to as “Vrishal” and “Kulheen” in the book. ● Arthashastra, written by Kautilya, is a treatise on polity during the Mauryan era. It introduces the Saptang theory of the state, which comprises seven elements: the King (Swami), Minister (Amatya), Territory (Janpada), Fort (Durg), Treasury (Kosa), Army (Danda), and Allies (Mitra). ○ The Ally (Mitra) is likened to the ear of the state. Allies assist the King in both peace and war. Kautilya distinguishes between idealistic and false allies, emphasizing the importance of natural alliances over artificial ones. ● Archaeological remains from the Mauryan period have been discovered in Bulandibagh and Kumrahar near Patna (ancient Pataliputra). ○ Chandragupta Maurya’s palace was reportedly made of wood. ○ D.B. Spooner conducted excavations in these areas, uncovering remains of the city wall in Bulandibagh and the palace in Kumhrar. ● Ashoka established the first hospital and herbal garden in India, along with public gardens and medicinal herb gardens. He also initiated projects like well-digging and tree planting for shade, and created a ministry for the welfare of indigenous and subject peoples. ● The term for a convoy of merchants in ancient India was “Sarthwah,” as described in Kautilya’s “Arthashastra.” ● Ashoka’s edicts mention several officials, including Yukta (district officials responsible for revenue collection), Rajjuka (rural officials with surveying and judicial duties), and Pradeshiya (top divisional officials comparable to modern-day commissioners). ● The name of Ashoka is mentioned in the Gujarra Minor Rock Edict, located in the Datia district of Madhya Pradesh, along the main road from Ujjain to Bharuch. ● Ashoka’s inscription in the Bhabru proves his adherence to Buddhism, where he refers to himself as “Piyadasi Raja” of Magadha. ● The Kanganahalli Buddha stupa in Karnataka features a stone portrait of Ashoka and his Queen, with the inscription “Ranya Ashoka” (King Ashoka). ● Ashoka’s Dhamma was centered on peace, non-violence, and religious tolerance, as mentioned in his 12th rock edict. ● The 13th inscription of Ashoka reveals his friendly relations with five Yavana (Greek) kings, including Antiochus II Theos, Ptolemy II Philadelphus, Antigonus Gonatas, the ruler of Cyrene, and Alexander Epirus. ● The earliest known copper plate, the Sohgaura, is a Mauryan record that contains the earliest royal order to preserve food-grains during famine. ● The Mahasthan inscription in the Bogra district, describes relief measures during a famine. ● Megasthenes categorized Mauryan society into seven groups, including philosophers, farmers, herdsmen, artisans, soldiers, overseers or spies, and assessors. He noted the absence of slavery and strict adherence to the caste system. ● Megasthenes’ “Indica” describes the administration of Pataliputra, including six committees of five members each. Town officials were referred to as “Astynomi.” ● Mauryan emperors significantly contributed to the development of culture, art, and literature. Chandragupta’s empire extended from Iran to North Karnataka. The Hindukush mountains served as India’s strategic frontier, and Ashoka’s inscriptions mention five provinces: Uttarapath, Avantiratha, Kalinga, Dakshinapath, and Prachyapatha. ● Sitadhyaksha was responsible for overseeing agricultural land and land revenue collection in the Mauryan empire, while Agronomoi served as district officers. ○ Shulkadhyaksha collected trade and service taxes, and Akradhyaksha managed mines. ● Revenue collection was supervised by Samaharta in the Mauryan ministerial council, while Antapal oversaw border forts and Pradeshtha administered commissionaries. ● Pautavadhyaksha was in charge of weights and measures, Panyadhyaksha managed the Commerce Department and Sunadhyaksha supervised the slaughterhouse. ● The penalty for causing dirt or siltation on roads in the Mauryan administration was known as “Pankodakasannirodhe.” ● The Arthashastra mentions two types of courts: Dharmasthiya, similar to modern civil courts, and Kantakshodhana, similar to modern criminal courts. ● Town administration during the Mauryan period was governed by municipalities, with the chief known as “Nagrak” or “Purmukhya.” |