VEDIC AGE

Introduction

- The Vedic Age spanned from 1500 to 600 BC, occurring in the late Bronze Age and early Iron Age of Indian history.

- It marked the period between the decline of the urban Indus Valley Civilization and the onset of the second urbanization phase, starting around 600 BC in the central Indo-Gangetic Plain.

- During this time, agricultural surplus, the development of crafts and trade, and population growth facilitated the emergence of towns in the Gangetic plains, known as the second urbanization in Indian history.

- Named after the Vedas, a collection of sacred texts composed during this period, the Vedic Age saw the self-identification of its composers as Aryans.

- The era is categorized into the Early Vedic Period (1500-1000 BC) and the Later Vedic Period (1000-600 BC).

Sources to Study Vedic Age

Literary Texts:

- Early Vedic Text: Rig Veda

- Later Vedic Texts: Samaveda, Yajurveda, Atharvaveda, and other texts

- Zend Avesta (Iranian text, 14th century BC):

- The Zend Avesta references the lands and deities of the Indo-Iranian speakers, mentioning regions in northern and northwestern India.

- Linguistic parallels between the Zend Avesta and the Vedas imply that the early Aryans may have originated from areas beyond the Indian subcontinent.

- Iliad and Odyssey, authored by Homer in the 8th century BC.

Inscriptions:

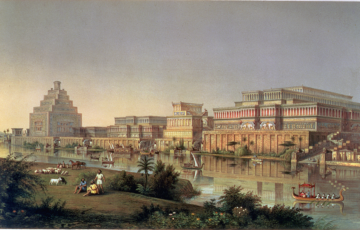

- Kassite inscriptions (1600 BC) and Mitanni inscriptions (1400 BC) in Iraq-Syria indicate a movement of a branch of Aryans from Iran westward into Iraq.

- The Boghazkoi Inscription, discovered in the Turkey-Syria (Bogazkoi) area and dated around 1400 BC, is the earliest inscription featuring names of Vedic Gods.

Archeological Sources:

- The Andronovo culture (2000–1150 BC) in Southern Siberia offers archaeological evidence of Aryan migrations, with their entry into India believed to have occurred from the Hindukush region (Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex).

- Excavations in Punjab, Uttar Pradesh, and northern Rajasthan, along the Indus and Ghaggar rivers, spanning from 1700 BC to 600 BC, provide archaeological insights into this period.

INDO-ARYANS

- A Linguistic term refers to speakers of a subgroup within the Indo-Iranian branch of the Indo-European language family.

- Arya: Cultural/ethnic term with an etymology from ‘ar‘ meaning to cultivate; literally translates to kinsmen, companion, or noble.

- Original home of Aryans: Subject to debate, with various theories proposed.

Theories related to Indo-Aryans

- Migration from Europe by William Jones and Morgan

- Semi-nomadic Aryans migrated to India from Eastern Europe, specifically from areas north of the Black Sea.

- Linguistic similarities: Indo-European languages such as Greek, Latin, German, and Sanskrit exhibit linguistic similarities.

- Example: Suryyas and Maruttash mentioned in Kassite inscriptions from Mesopotamia correspond to Vedic deities Surya and

- Central Asian Theory by Max Muller and E. Meyer Herzfeld

- They propose a theory suggesting a Central Asian origin for the Aryans.

- The ‘Avesta,’ an Iranian text, and the ‘Vedas’ demonstrate linguistic parallels. Both texts exhibit not only similarities in words but also shared concepts.

- Example: Words like Ahura (asura) and Haoma (soma) show interchangeable use of ‘h’ and ‘s’ indicating linguistic and conceptual similarities.

- Arctic Region Theory by Bal Gangadhar Tilak

- He proposed that the North Pole served as the original homeland of Aryans in the pre-glacial period, from which they migrated due to climate shifts.

- Evidence from Vedas: References within the Vedas mention phenomena such as six months of prolonged days and nights, which are characteristic of the Arctic region.

- Tibet Theory by Swami Dayanand Saraswati

- He suggested that Tibet was the original homeland of the Aryans.

- In Tibet, the worship of the sun and fire was prevalent due to the extreme cold climate. Saraswati noted that the flora and fauna described in the Rig-Veda were also present in Tibet, supporting his theory.

- Indian Theory by Dr. Sampurnanad and A.C. Das

- They proposed that India was the original homeland of the Aryans.

- The Vedas, especially the Rig Veda, highlight the Sapta Sindhu (Seven Rivers) region as their primary homeland.

- Linguistic evidence: Sanskrit, with its extensive repository of original Indo-European terms, indicates a closer linguistic relationship to the ancestral Aryan language compared to other European languages.

- The rituals detailed in the Vedic texts reflect practices rooted in Indian culture, supporting the theory of India as the original homeland of the Aryans.

EARLY VEDIC PERIOD (1500-1000 BC)

Geography

- Aryans primarily inhabited the Indus region, known as Saptasindhu or the land of seven rivers in the Rigveda.

- The seven rivers mentioned are Jhelum (Vatista), Beas (Vipasa), Chenab (Askini), Ravi (Purushni), Sutlej (Sutudri), Saraswati (Ghaggar or Hakra), and Indus (Sindhu).

- Their territory extended across present-day regions of Afghanistan, Punjab, and Haryana.

- Sindhu (Indus) river is the most frequently mentioned river, while Saraswati is regarded as the most revered (holy) river.

- The Saraswati Valley was referred to as Brhmavarta, the Himalayas as Himavant, and the Hindu Kush as Munjavant in the Rig Veda.

Political Structure

- Tribal kingdoms included the Bharatas, Matsyas, Yadus, and Purus.

- The Tribal Chief or Rajan served as the protector of the tribe, overseeing cattle, leading in warfare, and performing religious duties on behalf of the tribe.

- The Tribal Chief was alternatively known as Gopati or Gopa, signifying the protector of cows, while the queen was referred to as Mahisi.

- While the king’s position seemed hereditary, there were indications of election by the tribal assembly (samiti) to maintain a system of checks and balances.

- Tribal assemblies such as the Sabha, Samiti, Vidatha, and Gana played roles in deliberation, military affairs, and religious matters.

- Sabha: An assembly of elders or elites within the community.

- Samiti: Assembly consisting of the general populace.

- Vidatha: Assembly representing the entire tribe.

- Gana: Likely a clan-based organizational structure.

- Women had the opportunity to attend the sabha and vidatha assemblies.

Governance

- Absence of formal judicial system: There was no structured judicial system, and no specific officer was designated for administering justice.

- Use of spies: Spies were employed to prevent theft, especially of cattle, and burglary.

- Official titles: Although official titles didn’t directly indicate territorial administration, some roles were linked to specific territories.

- Purohita: Advised tribal chiefs and praised their actions in exchange for rewards like cows and slaves.

- Senani: Chief of the army, skilled in weaponry.

- Vrajapati: Responsible for pasture grounds and territorial control; they also led the Kulapas (family heads) or Gramanis (unit leaders) into battle.

- Evolution of roles: Over time, the roles of Gramani and Vrajapati became interchangeable.

Society

- Initially, society was divided based on “Varna” or color:

- Aryans, who were fair-skinned, and

- Non-Aryans, who were darker and spoke a different language.

- Non-Aryans, known as Dasyus, included Avrata (those who didn’t follow divine ordinances) and Akratu (those who didn’t perform sacrifices).

- Society was initially egalitarian, devoid of a caste-based system where occupations weren’t predetermined by birth, and a strict social hierarchy was absent.

- The Varna System emerged towards the end of the Rig Vedic age, mentioned only in the Purusashukta Hymn (Tenth Mandal of Rig Veda).

- Inequality began to emerge with tribal chiefs and priests gaining a larger share of resources, leading to the division of society into three groups: warriors, priests, and the common people, resembling the social structure in Iran.

- Slavery existed among Rig Vedic people, predominantly involving women slaves utilized for domestic purposes rather than agricultural labor.

- Cereal gifts were rarely documented, while evidence of land gifts was absent.

Family Structure

- Social structure was founded on brotherhood, with the primary unit being the ‘Kula‘ headed by a Kulapa and comprising members such as mother, father, son, and slaves.

- The fundamental societal unit was the family or Griha, led by the Grihapati, with his wife known as Sapatni, likely indicating a joint and patrilineal family setup.

- Multiple families formed a ‘vis’ or clan, while several ‘vis’ constituted a ‘Jana,’ representing the largest social unit.

- The term ‘Jana’ and ‘vis’ are found in the Rig Veda, but ‘Janapada’ is not mentioned.

- The ‘vis’ were subdivided into Grama or smaller tribal units primarily meant for military purposes. Conflict between Grama led to Samgrama or war.

- Marriages were predominantly monogamous, although instances of polygyny and polyandry were also present.

- In the Rig Veda, there is no expressed desire for daughters, although there is a recurrent theme of desire for children and cattle in the hymns.

Status of Women

- While society was predominantly patriarchal, women were afforded equal opportunities as men for their spiritual and intellectual growth.

- They could undergo rituals like Upanayana (Investiture ceremony), receive education, and participate in selecting life partners.

- Widow remarriage was also permitted.

- Noteworthy women poets such as Apala, Viswavara, Ghosa, and Lopamudra contributed to Vedic literature, indicating the recognition of women’s intellectual capabilities.

- Social practices like child marriage, sati, and purdah were absent during this period. The typical marriageable age appears to have been around 16 to 17 years old.

Military Structure

- The king did not maintain a standing army but relied on tribal units assembled during wartime. Military operations were carried out by tribal groups like Vrat, Gana, Grama, and Sardha.

- Aryans engaged in conflicts with pre-Aryan inhabitants and experienced internal tribal disputes, leading to the division of Aryans into five tribes or “Panchajana.”

- Dominant Aryan clans included the Bharatas and Tritsu, supported by the

- The Bharatas, led by Sudas, achieved victory over a coalition of ten rulers, comprising both Aryan and non-Aryan leaders, in the Battle of Ten Kings (Dashrajana) along the Parushni (Ravi) river.

- Subsequently, the Bharatas and Puru tribes merged to form the Kurus, with both the Pandavas and Kauravas belonging to this clan.

- Later, the Kurus allied with the Panchalas, establishing control over the Upper Ganga Valley.

- The conquered Dasas and Dasyus were treated as slaves and Sudras.

- Dasas, mentioned in ancient Iranian texts, were likely a branch of early Aryans, while Dasyus were likely the indigenous inhabitants of the region.

- Aryan chief Trasadayu subdued them.

- Aryan chiefs exhibited leniency towards Dasas but hostility towards Dasyus.

- Dasyus were possibly worshippers of the phallus and did not engage in cattle farming.

- Horse-drawn chariots

- It is said that the Indo-Aryans introduced horse-drawn chariots into both West Asia and India, along with improved weaponry such as coats of mail known as Varman.

- A coat of mail was typically an armored garment made of chain mail, interlinked rings, or overlapping metal plates, providing protection in battle.

- “Bharatavarsha” is thought to have derived its name from the Bharata tribe, a term first mentioned in the Rig Veda.

- It is said that the Indo-Aryans introduced horse-drawn chariots into both West Asia and India, along with improved weaponry such as coats of mail known as Varman.

Economy

Society was primarily pastoral, with cattle-rearing as the main occupation, and wealth was determined by the number of cows owned.

- Trade and commerce were limited, with the barter system prevailing, where the cow played a significant role as a key exchange item.

- Land ownership as private property was not established; instead, resources were shared collectively among clans. Individuals, including the Rajan (king), purohits (priests), and artisans, were integrated into clan networks.

- Primitive agricultural techniques involved fire-clearing methods and the use of wooden ploughs (langala and sura).

- The term “sita” referred to the furrow created by ploughing.

- Barley (yavam) and wheat (godhuma) were among the crops cultivated.

- Irrigation likely relied on wells, with water drawn using cattle-driven water-lifts equipped with pulleys.

- Various crafts were practiced, including carpentry, weaving, and chariot-making, with the latter holding prestige due to the popularity of chariot-racing.

- References in the Rig Veda indicate spinning, a task typically performed by women, and mention carpenters known as Takshan.

Taxation and Exchanges

- The economy relied on voluntary or compulsory contributions known as “Bali” from the people (vis) and war bounties.

- Social exchange was characterized by gift redistribution, extending courtesies, offering hospitality, and providing military aid.

- Iron technology was absent during this period, and there were limited metallurgical pursuits.

- The metal known as Ayas, likely either Copper or Bronze, was recognized.

- The Rig Veda mentions a smith, referred to as

- The term “Hiranya” is found in the Rig Veda, representing the oldest Sanskrit word for

Religion

- The Rig Vedic Aryans practiced worship of natural forces such as earth, fire, wind, rain, and thunder, primarily through rituals known as yajnas.

- A notable characteristic was Henotheism or Kathenotheism, where each hymn elevated a specific deity to supreme status temporarily.

- The Fire Cult was a distinct aspect associated with both Indo-Aryans and Indo-Iranians, emphasizing the importance of fire in religious rituals.

- Magic and omens were not prevalent in religious practices during this period.

- Meat consumption and sacrificial killing of animals were common, although cows deemed Aghnya (not to be killed) were exempt from sacrifice.

- Various deities, demigods, and spiritual entities were recognized and revered in religious observances during this period.

Important Deities

| Indra | ● Regarded as the greatest god among the Aryans, with approximately 250 hymns attributed to him.

● Known by epithets such as Purandhar (Breaker of forts), Urvarajit (Winner of fertile fields), Maghavan (Bounteous), and Vritrahan (Slayer of Vritra, chaos). |

| Agni | ● Second most important god, revered as the god of fire, with around 200 hymns dedicated to him.

● Serves as an intermediary between gods and humans, facilitating communication and offerings. |

| Varuna | ● Considered the third most important deity, Varuna is the god of water and is responsible for maintaining cosmic order (Rita). |

| Soma | ● Revered as the god of plants and often associated with the hallucinogenic Soma plant used in religious rituals.

● Viewed as the deity who inspires poets to compose hymns, with the entire 11th mandala of the Rig Veda dedicated to him. |

Other Gods:

- Rudra: Known as the god of destruction, later merged with Shiva in the later Vedic phase.

- Yama: Revered as the Lord of Death

- Pushan: Regarded as the god who looks after Sudras and cattle

- Surya: Identified as the son of Dyaus (the sky god)

- Vishnu: Revered as a benevolent and gentle god, later becoming a prominent deity in Hinduism associated with Dashavataras.

- Maruts: Worshiped as gods of storms, often depicted as young warriors riding chariots and wielding weapons.

- Ashvinis: Twin gods associated with war and fertility

Goddesses:

- Savitri: A solar deity, credited with the Gayatri Mantra in the 3rd mandala of the Rigveda.

- Aditi: Worshiped as the goddess of eternity and mother of the gods.

- Usha: Revered as the goddess of dawn.

- Sinivali: Worshiped as the goddess of fertility.

Demi-gods:

- Gandharvas: Divine musicians, often depicted as celestial singers and performers in the court of gods.

- Vishwadevas: Intermediate deities, representing various aspects of nature and the cosmos.

- Apasaras: Mistresses of the gods, associated with beauty, grace, and divine allure.

- Aryaman: Guardian of compacts and marriages, ensuring the fulfillment of agreements and the stability of relationships.

LATER VEDIC PERIOD (1000-600 BC)

The history of this age draws primarily from Vedic texts compiled post the Rig Vedic age. The Later Vedic culture, synonymous with the Painted Grey Ware (PGW) Culture, characterizes the Iron age.

- Tribes such as the Kurus, Panchalas, Vashas, and Ushinaras thrived during this period.

Geography

- Aryans expanded geographically towards eastern regions, extending up to Bengal, with a focal point in the Kuru-Panchala region encompassing the Indo-Gangetic divide and the upper Ganga Valley. Hastinapur emerged as their capital.

- Tribal kingdoms like Magadha, Anga, and Vanga thrived in the easternmost areas.

- The Kurus, formed from the amalgamation of Bharatas and Purus clans, initially resided between the Saraswati and Drishadvati rivers before migrating to occupy the upper Doab region, specifically Kurukshetra. References to these rivers are found in both Rig Veda and later Vedic texts.

- Later Vedic texts delineate India into three divisions:

- Aryavarta for Northern India with the Western Ganga Valley identified as ‘Aryavarta’.

- Madhyadesa for Central India

- Dakshinapatha for Southern India

Political Structure

State-level political organization began to emerge around 500 BCE, signifying the Later Vedic society’s transitional phase.

- Rig Vedic tribal assemblies waned in significance as royal authority strengthened, leading to the disappearance of Vidatha assemblies.

- Kin-based ‘Janas’ evolved into territory-based ‘Janapadas’, as evidenced in Brahmanas from around 800 BC.

- The term ‘Nagara’, denoting commercial quarters, is mentioned in later Vedic texts.

- However, large towns only started emerging towards the conclusion of the Vedic period. Hastinapura and Kausambi are regarded as proto-urban settlements, exhibiting urban-like characteristics.

- King: The authority of the Rajana, or king, became more pronounced, with titles such as Rajavisvajanan, Ahilabhuvanapathi (lord of all earth), Ekrat, and Samrat (sole ruler) being adopted.

- The concepts of Samrat/Samrajya began to develop.

- While hereditary kingship was on the rise, traces of elective monarchy emerged in Later Vedic Texts.

- Terms like rashtra (territory) and rajya (sovereign power) gained prominence.

- Key functionaries including the priest, commander, and chief queen aided the king in his duties.

- Village assemblies, under the authority of dominant clan chiefs, handled local affairs.

- Army: The king relied on mobilizing tribal units during wartime rather than maintaining a standing army.

- Wars: Warfare shifted from cattle raids to territorial conflicts as society transitioned to agriculture.

- Tribal chiefs accrued power at the expense of the peasantry, rewarding priests who helped maintain their authority through rituals like Rajasuya sacrifice, Ashvamedha, and Vajapeya, which emphasized territorial control.

- Ashvamedha: Asserting uncontested authority over a region where the royal horse roamed freely without interruption.

- Vajapeya: A chariot race ensuring the victory of the royal chariot over all kinsmen.

- Rajasuya: A royal consecration ceremony bestowing supreme power upon the king.

- Srauta sacrifices were conducted to regulate resources. These were sacrifices to achieve some benefits.

- Tribal chiefs accrued power at the expense of the peasantry, rewarding priests who helped maintain their authority through rituals like Rajasuya sacrifice, Ashvamedha, and Vajapeya, which emphasized territorial control.

Societal Status

- The varna system solidified social stratification into four main categories: Brahmanas, Kshatriyas, Vaishyas, and Shudras.

- Brahmanas were primarily associated with teaching, and their occupation held significant importance. Both the wives of Brahmanas and cows were accorded high status.

- Kshatriyas, referred to as Rajanyas, functioned as warriors and rulers, collecting ‘Bali’ as tax.

- Significant shifts occurred within the varna system, leading to increased privileges for both Brahmanas and Kshatriyas.

- The Panchavimsa Brahmana positioned Kshatriyas above Brahmanas, while the Satapatha Brahmana reversed the hierarchy, placing Brahmanas higher than Kshatriyas.

- The king asserted authority over all three varnas, with the Aitreya Brahmana noting the Brahmana as someone seeking support, subject to removal by the king.

- The emphasis on sacrificial rituals grew, amplifying the influence and power of the Brahmanas.

- Kshatriyas contested Brahmanical dominance and their exclusive right to enter the ashrams, which represented the regulated four-stage life of Brahmacharya, Grihastha, Vanaprastha, and Sanyasa.

- This challenge led to the emergence of alternative religious movements such as Jainism, Buddhism, and Ajivakam.

- The ashrama system, delineating various life stages, lacked full establishment during this period. While brahmacharya, grihastha, and vanaprastha were acknowledged, sannyasa had not yet evolved.

- The concept of Dvija (twice-born) emerged during this era.

- Upanayana (sacred thread ceremony) was restricted to the upper echelons of society, marking the initiation of education. Sudras and women were excluded from this privilege, unable to recite the Gayatri mantra.

- Certain artisan groups, like the Rathakaras (chariot makers), were granted elevated status, allowing them to wear the sacred thread.

- Vaisyas, initially involved in agriculture, cattle breeding, and crafts, later transitioned into trading roles, paying taxes to the kings.

- Some social groups were positioned below even Sudras, with the Chandala, a subset of the Panchamas (fifth varna), designated as untouchables and excluded from the varna hierarchy.

- Society was primarily rural, with urban elements beginning to emerge towards the period’s end, as evidenced by references to towns (nagar) in texts like the Taittiriya Aranyaka.

Family Structure

- The family served as a fundamental social unit, characterized by patriarchal structures and patrilineal descent, establishing hierarchical relationships within.

- Polygyny, the practice of taking multiple wives, was widespread.

- Household structures became more organized, with various rituals developed for family welfare, and the married man and his wife were regarded as the Yajamana.

- Joint families, encompassing three or four generations, lived together, as evidenced by archaeological findings in sites like Atranjikhera and Ahichchhtra in Western Uttar Pradesh, where communal food preparation was observed.

- The concept of gotra emerged during the later Vedic period, denoting a group of individuals tracing descent from a common ancestor.

- Marriage within the same gotra was prohibited, with individuals of the same gotra considered siblings, and intermarriage forbidden.

- Chandrayana prescribed as penance for men who violated this prohibition by marrying women of the same gotra.

- Numerous unilineal descent groups existed, sharing common ancestors, with related clans forming tribes.

- Marriage within the same gotra was prohibited, with individuals of the same gotra considered siblings, and intermarriage forbidden.

Women Status

- Women experienced a decline in societal status compared to the Rig Vedic age.

- Exclusion from assemblies and rituals marked a shift from their participation in the Rig Vedic period.

- Patriarchal family structures confined women’s roles to domestic duties.

- Practices such as Sati and Child Marriage were prevalent.

- Daughters were sometimes viewed negatively, labeled as a source of sorrow, as seen in the Aitreya Brahmana.

- Despite societal constraints, exceptional women like Gargi and Maitreyi distinguished themselves in knowledge domains, with Gargi notably engaging in philosophical discourse and outwitting Yajnavalkya.

Economy

| Agriculture | ● Agriculture emerged as the primary livelihood, employing methods like tree clearing through burning and plough-based cultivation elaborated in the Satapatha Brahmana.

● Iron agricultural tools were scarce, with wooden plough extensively used. ● Barley, rice, and wheat were cultivated, with wheat as the staple food in the Punjab region and rice gaining prominence in the Ganga-Yamuna doab. Rice was notably used in Vedic rituals. ○ Barley (Yava) production persisted, while rice (Vrihi) and wheat (Godhuma) became primary crops alongside lentils. ● Farming Practices: Mixed farming, combining cultivation and herding, was common. |

| Transportation | ● Oxen-drawn wagons were prevalent for transportation. |

| Land Ownership | ● Land was communally owned, with participatory rights held by the clan (vish), and the head of the household (Grahpati) was the landowner. |

| Trade and Exchange | ● Barter remained the primary mode of exchange, with ornaments like “Nishka” used in trade.

● Shreni, associations of traders, merchants, and artisans, were led by a Shreshthi. |

| Taxation | ● Taxes and tributes, primarily from the Vaishyas, were collected by Sangrihitri (the tax collector) contrasting with the Rig Vedic Age where taxation was not mandatory. |

| Development of Trade | ● Trade and exchange flourished, evidenced by archaeological findings indicating commodity movement and the existence of specialized caravan traders.

● Coins were not yet in circulation; barter remained the medium of exchange until the introduction of coins around 600 BCE. |

Metals Known

- Iron usage commenced around 1200 BC, referred to as Krishna Ayas/Shyama Ayas.

- By 1000 BC, it was utilized in regions like Gandhara, eastern Punjab, western Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, and Rajasthan.

- Excavations revealed Aryans employing iron weapons such as arrowheads and spearheads in western Uttar Pradesh around 800 BC.

- Iron axes were utilized for forest clearing in the upper Gangetic basin, with iron knowledge spreading to eastern Uttar Pradesh and the Videha (Mithila) region by the later Vedic period.

- Various metals including copper, tin, gold, bronze, and lead are mentioned.

- Copper objects were crafted for weapons used in warfare and hunting.

- Knowledge of glass manufacturing was present among them.

Arts and Crafts

- Pottery: Four main pottery types were prevalent: Painted Grey Ware, Black and Red Ware, Black-slipped Ware, and Red Ware.

- Burnt bricks were not commonly used.

- Craftsmanship: Weaving, leatherwork, pottery, and carpentry were well-established.

- Terms like Kulala for potters and Urna sutra for wool are mentioned.

- Specialized Professions:

- Various specialized professional groups existed, including bow makers, rope makers, arrow makers, hide dressers, stone breakers, physicians, goldsmiths, and

- Other professions mentioned include physicians, washermen, hunters, boatmen, astrologers, and cooks.

- Performers of Vedic sacrifices also served as service providers.

- Animal Related Crafts: References to elephants and elephant keepers are found in the Atharva Veda, indicating their significance in the society of the time.

Religion

The upper Ganga Doab, known as the land of Kuru-Panchalas, served as the hub of Aryan culture during the Later Vedic period.

- Emergence of Idolatry: Signs of idol worship began to emerge during this time.

- Shift in Reverence Towards Gods:

- Rig Vedic deities like Indra and Agni were gradually supplanted by Prajapati (the creator), Vishnu (the preserver and protector), and Rudra (the god of rituals).

- The Satapatha Brahmana enumerates Rudra’s names as Pasunampatih, Sarva, Bhava, and Bahikas, while Vishnu was perceived as the protector without mention of his incarnations.

- Importance of Sacrifices:

- Animal sacrifices gained prominence, overshadowing prayers in appeasing the gods.

- Emphasis was placed on the correct execution of rituals and the payment of Dakshina.

- Complexity of Rituals:

- Rituals became more intricate, demanding greater resources and time.

- The reliance on rituals and sacrifices as solutions to problems fostered the belief that material wealth could achieve anything, contrary to the teachings of the Upanishads, which stressed self-realization.

- Development of Heterodox Faiths:

- Dissension arose against priestly dominance and sacrificial practices, leading to the emergence of heterodox faiths like Buddhism and Jainism, which emphasized correct human behavior and discipline.

- Division of Deities by Varna: Each varna had its own deities, reflecting societal divisions.

- Pushan was revered as the god of the Shudras, responsible for safeguarding cattle.

- Sacrificial Gifts:

- Cows, gold, cloth, and horses were presented as sacrificial offerings.

- While priests occasionally claimed portions of territory as Dakshina, the practice of granting land as a sacrificial gift was not firmly established.

- Offerings in Rituals:

- Agricultural produce, including cooked rice (with wheat rarely used), became common offerings in rituals.

- Til, from which the first widely used vegetable oil was derived, found its way into rituals.

- Towards the Later Vedic age’s conclusion, resistance to priestly dominance, cults, and sacrificial practices emerged, particularly in regions like Panchala and

Education

- Development of Disciplines: The Later Vedic period saw the emergence and development of various disciplines such as philosophy, literature, and science.

- Branches of learning including literature, grammar, mathematics, ethics, and astronomy flourished during this time.

- Vedic System of Education: It emphasized the importance of pronunciation, grammar, and oral transmission, suggesting training in recitation and memorization as integral components of education.

- The composition of Upanishads, also known as Vedanta due to their attachment as the concluding part of Vedic texts, occurred during this period.

- Gender Limitations: Education was exclusively reserved for males during this era, with females excluded from formal learning opportunities.

- Teacher-Pupil Relationship: It was centered on personalized training, fostering close mentorship and guidance between the teacher and student.

Literature

- The term ‘Veda’ originates from the root ‘vid,’ meaning ‘to know,’ symbolizing ‘superior knowledge.’

- Vedic literature comprises of Four Vedas: Rigveda, Samaveda, Yajurveda, and Atharvaveda. Each of the Vedas is indeed divided into four parts or sections.

- Samhitas: These are collections of hymns and verses, forming the foundational texts of the Vedas.

- Brahmanas: These texts contain prose explanations and discussions of the rituals and ceremonies described in the Samhitas.

- Aranyakas: Literally translating to “forest books,” these texts provide philosophical and symbolic interpretations of the rituals described in the Brahmanas. They were often studied by hermits in forest retreats.

- Upanishads: These texts explore profound philosophical concepts, delving into the nature of reality, the self (Atman), and the ultimate truth (Brahman). They are considered the culmination of Vedic thought and form the basis of Hindu philosophy.

- The Samhitas and Brahmanas together constitute the Karma-Kanda segment of the Vedas, which primarily deals with rituals and sacrificial ceremonies.

- The Aranyakas and Upanishads are often referred to as Vedanta or the “end of the Veda,” and form the Gyan-Kanda segment, focusing explicitly on philosophy and spirituality.

- Despite their oral transmission tradition, the Vedas were eventually transcribed into written form, with the earliest surviving manuscript dating back to the 11th century.

| Shruti | ● These are texts considered “heard” or the product of divine revelation to great sages (Rishis) during meditation (Dhyaan).

● Shruti includes the four Vedas and their Samhitas. ● These texts are recollected by normal humans. |

| Smriti | ● Smriti refers to texts that are remembered or recollected by normal humans.

● It encompasses detailed commentaries and explanations on the Vedas, including Brahmanas, Aranyakas, and Upanishads. ● Additionally, Smriti includes the six Vedangas (limbs of the Vedas) and Upavedas (secondary Vedas). |

THE FOUR VEDAS

| Rig Veda | ● Oldest surviving text, addressing the concept of the Origin of the Universe.

● The Rigveda comprises 1028 hymns and 10552 mantras, making it an ancient collection of Vedic Sanskrit hymns. ● Divided into 10 Mandals (books): o Books II to VII constitute the earliest sections. o Books I and X were later additions, incorporating the Purusashukta explaining the concept of the four varnas. o Book VIII mainly relates to Kanva’s family, while Book IX is a compilation of Soma hymns. ● Collection of hymns and prayers dedicated to various deities and natural forces like Agni, Indra, Mitra, and Varuna, presented by different families of poets or sages (family books). ● The tradition of Vedic chanting was recognized by UNESCO as intangible heritage. ● Although composed in Sanskrit, it contains numerous Munda and Dravidian words, likely integrated through the languages of the Harappans. |

| Sama Veda | ● It consists of hymns consists of a total of 1875 verses, many of which are borrowed from the Rigveda, known for their lyrical and melodious nature.

● Earliest book on music (Sama means melody; ragas and raginis). ● Poetic texts derived from Rig Veda, including the famous Dhrupada raga, later sung by Tansen. |

| Yajur Veda | ● The term “Yajurveda” in Sanskrit translates to the “wisdom of sacrificial formulas.”

● This Veda, compiled approximately a century or two after the Rig-Veda, comprises prose and verse formulas intended to be recited by priests performing the manual aspects of rituals. ○ It provides detailed procedures for various rites and sacrifices, often utilizing hymns from the Rig-Veda. ● The Samhitas of the Yajur Veda are divided into two main parts: ○ The Shukla Yajur Veda / White Yajur Veda / Vajasaneya includes a distinct Brahmana text known as the Satapatha Brahmana. This part contains only the Mantras/Poetic foms, with the Madhyandina and Kanva recensions. ○ The Krishna Yajur Veda / Black Yajur Veda incorporates Brahmana texts comprises both poetic and prose elements, discussing various ritualistic and philosophical topics. |

| Atharva Veda | ● It contains knowledge of the physical world and spirituality, offering insights into various aspects of life.

● Contains content on magic, charms, omens, agriculture, industry/craft, cattle rearing, and cures for diseases. ● The Gopatha Brahmana stands as the sole Brahmana text affiliated with the Atharvaveda. It is linked with both the Shaunaka and the Paippalada recensions of the Atharvaveda. ● Ayurveda, the ‘Science of Life,’ first appeared in the Atharvaveda, serving as an Upaveda. It encompasses various aspects such as disease prevention, loyalty, marriage, and love poetry, reflecting the beliefs and practices of common people. |

Brahmanas:

- Describe rules for sacrificial ceremonies and explain Vedic hymns in an orthodox manner.

- Each Veda has several Brahmanas attached to it, with the Satpatha Brahmana (attached to the Yajur Veda) being the most important and exhaustive.

Aranyakas:

- Also known as the “forest books,” composed mainly by hermits living in forests for their pupils.

- Deal with mysticism, philosophy, and oppose sacrifice.

- Emphasize meditation and provide philosophical interpretations of rituals.

- Composed during the later Vedic period.

Upanishads:

- Literally means “sitting near someone,” records philosophical dialogues between teachers (Gurus) and students (Shishyas).

- There are 108 Upanishads, with 13 being the most prominent.

- Notable Upanishads include the Mandukyopanishad, which mentions “Satyamev Jayate,” and the Chhandogya Upanishad, which refers to the first three ashrams.

- Dara Shukoh, a Mughal prince, translated the Upanishads into Persian in 1657 under the title Sirr-e-Akbar.

- The Jabala Upanishad mentions a 4-fold ashram (stages) for 4 Purusharthas (goals), applicable to Brahmacharya (Celibate Student), Grihastha (Householder), Vanaprastha (Hermit in Retreat), and Sanyasa (Renunciation).

Vedanta:

- Philosophical and spiritual traditions evolved from the Upanishads, signifying the final objective of the Vedas.

- Criticizes sacrifices and rituals, representing the concluding phase of the Vedic era.

Vedanga:

- Translates to “limbs of the Vedas,” serving as supplementary texts aiding in proper recitation and comprehension of the Vedas.

- Not classified as Shruti, considered of human origin and presented in the form of Sutra (condensed statements).

- Includes six branches:

- Siksha: Pronunciation and education.

- Nirukta: Origin of words.

- Chhanda: Metrics in Sanskrit verses.

- Jyotish: Astrology.

- Vyakaran: Sanskrit grammar.

- Kalpa: Knowledge of rituals (Dharma sutras).

UPSC PREVIOUS YEAR QUESTIONS

1. With reference to the difference between the culture of Rig Vedic Aryans and Indus Valley people, which of the following statements is/are correct? [UPSC CSE 2017]

1). Rig Vedic Aryans used the cost of mail and helmet in warfare whereas the people of Indus Valley Civilization did not leave any evidence of using them.

2). Rig Vedic Aryans knew gold, silver, and copper whereas Indus Valley people knew only copper and iron.

3). Rig Vedic Aryans had domesticated the horse whereas there is no evidence of Indus Valley people having been aware of this animal.

Select the correct answer using the code given below:

a) 1 only

b) 2 and 3 only

c) 1 and 3 only

d) 1, 2 and 3

2. The religion of early vedic Aryans was primarily of : [UPSC CSE 2012]

a) Bhakti

b) Image Worship and Yajna

c) Worship of Nature and Yajna

d) Worship of Nature and Bhakti

3. The national motto of India, ‘Satyameva Jayate’ inscribed below the Emblem of India is taken from [UPSC CSE 2014]

a) Katha Upanishad

b) Chandogya Upanishad

c) Aitreya Upanishad

d) Mundaka Upanishad

Answers: 1. C , 2. C , 3. C

| IMPORTANT FACTS RELATED TO THE CHAPTER

● Atranjikhera is an archaeological site located on the bank of the Kali river, a tributary of the Ganga. ○ Initially identified by Sir Alexander Cunningham in 1862, it was later excavated by R.C. Gaur in 1962. The site provides evidence of iron usage dating back to 1150 B.C. ● The Upanishads mention Kshatriya kings who were renowned scholars and philosophers, imparting knowledge to Brahmins. ○ Notable among them were King Janak of Videha, King Pravahanjabali of Panchal, King Asvapati of Kekaya, and King Ajatshatru of Kashi. ● The concept of salvation or Moksha, meaning liberation, is introduced in the Upanishads, diverging from the idea of the continuous cycle of life and death as the ultimate aim of the human soul. ○ According to the Upanishads, the essence of the self lies not in the body or mind, but in the Atman (Soul). ● The Kathopanishad recounts the dialogue between Yama, the Lord of Death, and Nachiketa, a young boy of twelve who ventures in search of the meaning of death and existence beyond. This narrative constitutes the subject matter of the Katha Upanishad or Kathopanishad. ● During the Vedic period, the Sindhu (Indus) River held significant importance, being frequently mentioned in the Rig Veda. ○ Due to its economic significance, the Sindhu River was referred to as ‘Hiranyani,‘ and its point of termination was described as ‘Peravat,’ signifying the Arabian Sea. ● In contrast, the Saraswati River was revered as the most sacred river by the Rigvedic Aryans and was known as “Naditama.” ● In the Post-Vedic period, the Hindu tradition recognized four stages (ashramas) in human life: Brahmacharya, Grihastha, Vanaprastha, and Sanyasa, along with four purusharthas: Dharma, Artha, Kama, and Moksha. ● The concepts of Dharma and Rita appear in the Rig Veda, with Dharma referring to cosmic ordinance and Rita closely associated with universal harmony, portraying an impersonal law maintaining cosmic order. ● Brihaspati, also known as Deva-guru, serves as the teacher or priest of the Gods, acting as the guru of the Devas. ● Women known as Brahmavadini composed many hymns in the Rig Veda, including notable figures like Lopamudra, Vishwawara, Sikta, Nivavari, and Ghosa. Lopamudra was the wife of the sage Agastya. ● The Shatapatha Brahmana recounts the story of King Videgha Madhava, accompanied by his priest Rishi Gautama Rahugana, carrying the sacred fire to the east, preserving cultural traditions for the Kosalas and the Videhas. ● In the post-Vedic period, the region of Kuru and Panchala was regarded as the focal point of Aryan culture due to significant advancements in science, mathematics, astronomy, religion, and philosophy. ● The term “gotra” originated from the Rigvedic period, initially denoting “cow shelter” or “herd of cows,” later evolving to signify “family” or “lineage kin” during the post-Vedic period. ● Early Vedic Aryans primarily worshipped nature and performed Yajnas (sacrifices). They viewed life as a manifestation of nature and believed in the divine power behind natural elements like fire, water, and wind. ● Sacrifice, or Yajna, was central to Rigvedic religion, with domestic and community sacrifices being common practices believed to please the Gods. ● The Rig Veda mentions the Dasharajnya or ‘War of 10 Kings’ fought on the banks of the Parushni River. ○ Sudas, a descendant of King Bharata, achieved a significant victory in this war. ● Monarchy, particularly hereditary monarchy, was the prevailing system of governance during the Vedic era, although instances of election by the people were also observed. ● The Rigveda references several tribal or clan-based assemblies such as Sabha, Samiti, and Vidatha, with Sabha primarily associated with judicial functions. ● The Gayatri Mantra, first written in Sanskrit in the Rigveda by the Brahmarshi Vishwamitra, expresses the aspiration for divine enlightenment and guidance along the righteous path. ● The Puranas possess five characteristics, including Sarga (creation), Pratisarga (renovation), Vansa (genealogy of sages and gods), Manvantara (periods of Manus), and Vanshanucharita (genealogy of kings). They are considered sacred literature in Hinduism, there are 18 Puranas: Matsya Purana Markandeya Purana, Bhagavat Purana, Bhavishya Purana, Brahmanda Purana, Brahma Vaivrata Purana, Brahma Purana, Vamana Purana, Varaha Purana, Vishnu Purana, Vayu Purana, Agni Purana, Narada Purana, Padma Purana, Linga Purana, Garuda Purana, Skanda Purana, Kurma Purana. ○ Among these, Srimad Bhagavatam is esteemed as the ‘Crown Jewel’ of Vedic literature. ● Shrimad Bhagavad Gita, often referred to simply as the Gita, was originally written in Sanskrit and contains 700 verses. It is a part of the epic Mahabharata. ● The statement “Tamsoma Jyotirgamaya” originates from the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, meaning “lead us from darkness to light” or “lead us from ignorance to truth.” ● Satyakama Jabala, depicted as a boy and later a Vedic sage, challenges the stigma of an unmarried mother. His story is found in Chapter IV of the Chhandogya Upanishad. ● The concept of ‘Rit,’ representing the universal principle of natural order, has its origins in the Vedas. ○ ‘Rit’ forms the basis of Indian culture, legal theory, politics, and philosophy. ○ Varuna, the God, was believed to uphold ‘Rit’ or the natural order, earning him the title ‘Ritasyagopa.’ ● 16 Sanskars, or rites of passage, are described in Hinduism. ○ Three are performed before birth, twelve during life, and one after death. ○ Among them, the Upnayan Sanskar, wedding ceremony, and post-death rituals are the most significant and commonly performed. |