The senior advocate’s Conundrum

Context: The Central government is seeking to change guidelines for the designation of senior lawyers, issued by the Supreme Court in the aftermath of its 2017 ruling in the case of ‘Indira Jaising vs. Union of India’. An application for modification was filed before the Apex Court in ‘Amar Vivek Aggarwal & Others vs. High Court of Punjab and Haryana & Others. The Centre looked to revisit parameters for determining the designation of senior advocates, citing the 74th paragraph of the 2017 ruling (Para 36 in the main judgement) which had acknowledged that the guidelines are not exhaustive and left them “open for consideration by this Court at such point of time that the same becomes necessary.

What are these guidelines that the Centre seeks to modify?

- In October 2018, the Apex Court released a list of Guidelines to Regulate the Conferment of Designation of Senior Advocates.

- This came after its 2017 decision in a case filed by India’s first woman Senior Advocate Indira Jaising (‘Indira Jaising vs. Union of India’), for greater transparency in the process of designating.

- The guidelines discouraged the system of ‘voting by secret ballot”, except in cases where it was “unavoidable.”

- According to the 2018 guidelines, a “Committee for Designation of Senior Advocates” or a “permanent committee” was created and empowered with powers of conferment.

- The CJI-chaired committee was to consist of two senior-most SC judges, the Attorney General of India, and a “member of the Bar” nominated by the chair and other members. The Committee was to meet twice a year, at least.

- The CJI or any other judge could recommend the name of an advocate for designation.

- Alternatively, advocates could submit their applications to the “Permanent Secretariat”, which would evaluate them on criteria like 10-20 years of legal practice, be it as an advocate, district judge, or judicial member of an Indian tribunal where qualification for eligibility is not less than that prescribed for a district judge.

Situation before the 2017 ruling?

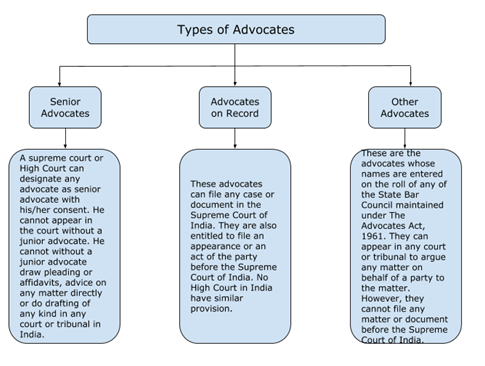

- Section 16 (1) of the Advocates Act, 1961 states “there shall be two classes of advocates, namely, senior advocates and other advocates.”

- However, Section 16 (2) allows an advocate to be designated as a senior advocate if he consents to it, and “if the Supreme Court or a High Court is of opinion that by virtue of his ability, he is deserving of such distinction.

- Further, it was the Chief Justice and the judges who designated an advocate as a ‘senior’ advocate.

What did the court decide in the ‘Indira Jaising’ case?

- In October 2017, a three-judge bench of the Apex Court headed by then Justice Ranjan Gogoi decided to lay down guidelines for itself and all High Courts on the process of designating senior advocates.

- Jaising challenged the existing process as “opaque”, “arbitrary” and “fraught with nepotism.”

- It was this judgement that decided the setting up of a “permanent committee” and a “permanent secretariat”, a body tasked with receiving and compiling all applications for designation with relevant data, information, and the number of reported and unreported judgments.

- After this, the proposal for designation is to be published by it on the official website of the concerned court, inviting suggestions and views, which shall then be forwarded to the permanent committee for scrutiny.

- The committee then interviews the candidate and makes an overall evaluation based on years of practice, pro-bono work undertaken, judgments, publications, and a personality test.

- Once a candidate’s name is approved, it will be forwarded to the Full Court to decide on the basis of the majority. The Full Court can also recall the designation of a senior advocate.

Why is the Centre trying to modify the guidelines now?

- The Central government is seeking to modify the 2017 order on the designation guidelines for lawyers based on a “point-based system”, which awarded 40% weightage to publications, personality, and suitability gauged through the interview.

- The Centre argued that this system is subjective, ineffective, and dilutes the “esteem and dignity of the honour being conferred traditionally.”

- The application points to the rampant circulation of “bogus” and “sham” journals where people can publish their articles without any academic evaluation of the contents and quality of the articles, simply by “paying a nominal amount”.

- Centre argues in its application that the titles ‘Senior counsel’, ‘Senior Advocate’ and ‘King’s Counsel’ are traditionally bestowed on distinguished lawyers practising in current or former Commonwealth countries or jurisdictions who the “court feels deserve such an “honour” and recognition” owing to their exceptional competence, contribution to the development of law, advocacy and several other factors.

- Further, the Centre argues that the current requirements for designation are irrelevant and have resulted in “ousting otherwise eligible candidates” based on factors that are “not germane to the issue of being designated as a Senior Advocate.

- Finally, the application seeks to reinstate the rule of a simple majority by a secret ballot, where the judges can express their views about the suitability of any candidate “without any embarrassment,” reasoning that the secret ballot will minimise campaigning for votes by lawyers.

| Practice Question

1. What are the guidelines for designation of Senior advocate in India? What changes it need? |