Supreme Court’s Landmark Ruling on Disability Rights and Educational Opportunities

Syllabus:

GS 3:

- Government Policies and Intervention for development of vulnerable sections of society.

- Development and management of Education

Why in the News?

The Supreme Court’s recent ruling on October 15 reaffirmed educational opportunities for persons with disabilities (PwD) and rejected rigid standards that could exclude candidates based solely on disability thresholds, promoting inclusive education.

Positive Obligations of the State

- Legal Obligation: The Supreme Court’s ruling emphasized the positive duty of the state and institutions to create an enabling environment for PwD, aligned with the RPwD Act, 2016.

- Nuanced Evaluation: The court directed disability-assessment boards to assess disabilities on an individual basis, considering how each disability impacts the ability to pursue education or a career.

- Beyond Percentages: A mere percentage threshold of disability is inadequate; the focus should be on how disability specifically affects an individual’s participation in education or profession.

- Rights-Based Approach: The ruling promotes a rights-based approach to education, ensuring institutions assess PwD candidates based on potential, not limitations.

- Inclusive Education: Institutions must provide a conducive environment that accommodates diverse learning needs to ensure PwD can fully participate in educational and professional arenas.

Reasonable Accommodation

- Conceptual Understanding: Reasonable accommodation refers to necessary adjustments that allow PwD to enjoy equal opportunities without undue burden on institutions or society.

- Legislative Support: The RPwD Act, 2016 mandates reasonable accommodation for PwD, covering modifications in education, employment, and public spaces to ensure inclusivity.

- Judicial Reference: The court referenced previous rulings, like Vikash Kumar Vs UPSC (2021), which established that reasonable accommodation is key to the state’s duty in supporting PwD.

- Beyond Physical Aids: The ruling stressed that reasonable accommodation isn’t limited to physical aids but also includes structural changes that enable meaningful participation.

- Holistic Approach: A flexible interpretation of reasonable accommodation is needed to uphold the inherent dignity of PwD, aligning with the RPwD Act and Article 41 of the Constitution.

Principle of Equality

- Equality Redefined: Equality for PwD goes beyond preventing discrimination; it includes positive actions that foster full participation in social and educational contexts.

- Anti-Discrimination Laws: The judgement emphasized that anti-discrimination laws are not enough; institutions must actively remove barriers and create conditions for PwD to thrive.

- Facial Equality Rejected: The Supreme Court rejected superficial equality, underscoring that true equality involves individualized assessment rather than applying blanket standards.

- Constitutional Mandate: The ruling draws on Article 14 of the Constitution, reinforcing the need for flexible approaches to ensure PwD are given equal opportunities in education.

- Legal Precedents: Key judgments like Ravinder Kumar Dhariwal (2023) and Jceja Ghosh Vs Union of India (2016) shaped the court’s stance on equality, advocating for contextual evaluations of disabilities.

Inclusive Education

- Legal Definition: Inclusive education, as defined in the RPwD Act, means that students with and without disabilities learn together, with necessary adjustments for diverse learning needs.

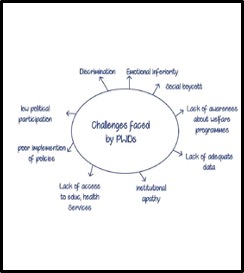

- Barriers to Inclusivity: The judgement acknowledged existing barriers like inadequate resources and infrastructure but stressed the moral imperative to remove them for an inclusive system.

- Shifting Paradigm: The ruling represents a shift from integration to inclusivity, where institutions adapt to individual abilities and challenges rather than impose uniform standards.

- Resource Allocation: Educational institutions must invest in assistive technologies, flexible curricula, and infrastructure to support inclusive education effectively.

- Moral Obligation: The court emphasized that the approach to PwD should focus on how best to accommodate them, not how to disqualify them from educational opportunities.

Individualized Assessments

- Disability as Unique: The ruling acknowledged that disabilities affect individuals differently, requiring a more tailored approach to support and accommodations in education and beyond.

- Regulatory Reforms: Regulatory bodies like NIMC were directed to revise rules that automatically exclude PwD based on rigid disability benchmarks, promoting more flexible standards.

- Sector-Wide Implications: The ruling’s impact extends beyond education, setting a precedent for sectors like employment and healthcare to adopt individualized assessments for PwD.

- Framework for Inclusivity: The judgement paves the way for policies that prioritize inclusivity over limitations, reshaping educational and professional standards across the country.

- Potential vs. Limitations: The emphasis on individual potential encourages institutions to assess candidates based on abilities, rather than disqualifying them for their disabilities.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court’s ruling marks a significant step towards inclusivity, reinforcing the importance of individualized support and flexible educational frameworks for PwD. This decision sets a foundation for a more inclusive society that respects the dignity and autonomy of every individual.

Source: The Hindu

Mains Practice Question

Discuss how the Supreme Court’s ruling on reasonable accommodation for persons with disabilities promotes inclusivity in educational and professional sectors. Analyze its broader implications for society.

Associated Article:

https://universalinstitutions.com/empowering-disability-inclusion-in-india/