REVISITING SUB-QUOTAS: SUPREME COURT’S STANCE ON SCHEDULED CASTES’ SUB-CLASSIFICATION

Syllabus:

- GS-2- Reservation system in India , Fundamental rights , Judicial review

Focus :

- The article explores the Supreme Court’s recent judgment allowing States to sub-classify Scheduled Castes (SC) for the purpose of creating sub-quotas within the broader reservation system. It examines the rationale behind overruling a previous judgment, the debate over the homogeneous nature of SCs, and the evolving discourse on creamy layer exclusion within SC communities.

Source-HT

Introduction: The Supreme Court’s Ruling on SC Sub-Quotas

- Recent Judgment: A seven-judge Bench of the Supreme Court has ruled that States have the authority to sub-classify Scheduled Castes (SCs) into smaller groups to create sub-quotas within the broader reservation framework. This decision overrules a 2004 judgment that had declared such sub-classification impermissible.

Background: The 2004 E.V. Chinnaiah Judgment

- Context: In 2004, a five-judge Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court ruled in the case of E.V. Chinnaiah vs State of Andhra Pradesh that sub-classification of Scheduled Castes was unconstitutional.

- Andhra Pradesh Law: The case arose from an Andhra Pradesh law that created four sub-groups (A, B, C, and D) within the SC community, each with its own reservation percentage, to address disparities in representation among SC communities.

- Supreme Court’s Rationale in 2004: The Bench held that under Article 341 of the Constitution, the President alone could notify and modify the list of Scheduled Castes. It declared that once notified, SCs should be treated as a homogeneous class, and sub-classification by State legislatures was deemed unconstitutional.

Emergence of a Larger Bench: Revisiting the 2004 Judgment

- New Challenges: The issue of sub-classification arose again in cases from Punjab, Haryana, and Tamil Nadu, where State laws had provided for sub-quotas among SC communities. These laws were challenged and initially struck down based on the 2004 Chinnaiah judgment.

- Supreme Court’s Doubts: A Constitution Bench in 2020 expressed doubts about the correctness of the Chinnaiah ruling, noting that the Indra Sawhney case (1992) had allowed for sub-classification within Other Backward Classes (OBCs). However, Chinnaiah had refused to extend this principle to SCs, leading to the formation of a larger Bench to revisit the issue.

The New Ruling: Sub-Classification of Scheduled Castes

- Overruling Chinnaiah (2004): The seven-judge Bench, led by Chief Justice D.Y. Chandrachud, ruled that the 2004 judgment was incorrect in its assertion that SCs form a homogeneous class. The Bench held that sub-classification is permissible under certain conditions.

Reasoning

- Heterogeneity Among SCs: The Bench noted that while all SCs share a common constitutional identity due to their experience of untouchability, there are significant differences in their socio-economic conditions. This heterogeneity justifies sub-classification.

- Empirical Evidence: Historical and empirical evidence shows disparities within the SC community, with some sections facing discrimination from others. The Court emphasized the need for an “intelligible differentia” (clear criteria) for sub-classification.

- No Violation of Article 341: The Court clarified that sub-classification does not amount to modifying the Presidential list of SCs under Article 341, which remains the exclusive domain of the President. Instead, it allows States to address varying degrees of backwardness within the SC community.

Implications for States: Earmarking Sub-Quotas

- Empowerment of States: The ruling empowers States to create sub-quotas within the SC reservation framework, potentially benefitting the most marginalized sections who have not fully enjoyed the benefits of reservation.

- Judicial Review: Any sub-classification by States will be subject to judicial review, ensuring that the criteria used are rational and based on empirical data.

Dissenting Opinion: Justice Bela Trivedi

- Opposition to Sub-Classification: Justice Bela Trivedi dissented, upholding the Chinnaiah doctrine that SCs should be treated as a homogeneous class. She argued that sub-classification amounts to tinkering with the Presidential list under Article 341, which she believes is impermissible.

The Debate on Creamy Layer Exclusion

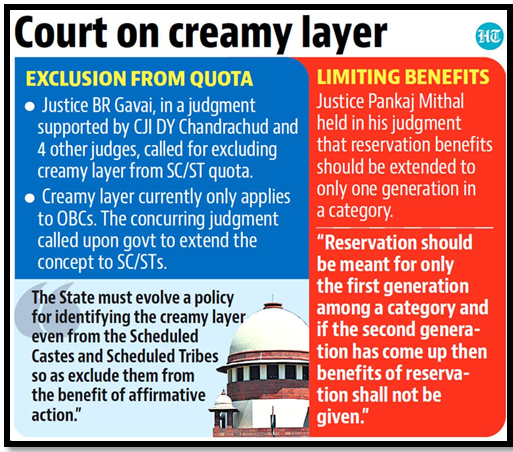

- Current Scope: The concept of creamy layer exclusion is currently applicable only to OBCs, preventing the more affluent among them from benefiting from reservations.

Justice B.R. Gavai’s Opinion:

- Advocacy for Creamy Layer: Justice Gavai, in a concurring opinion, suggested that a similar principle could be applied within the SC community to ensure that the benefits of reservation reach the most disadvantaged.

- Equality and Access: He highlighted the disparities within SCs, pointing out that children of affluent SC families in urban areas with access to elite education should not be treated the same as those in rural areas with limited resources.

- Custom Parameters: However, he also noted that the criteria for identifying the creamy layer within SCs should differ from those used for OBCs, acknowledging the unique socio-economic challenges faced by SCs.

Implications for Government Policy

- No Immediate Direction: While the opinions on creamy layer exclusion within the SC community reflect a significant judicial perspective, they do not constitute a directive to the government. The issue did not directly arise in this case, leaving it open for future policy decisions.

- Future Considerations: The discussion on creamy layer exclusion within SCs may influence future debates and policy-making, potentially leading to more nuanced approaches to affirmative action.

Conclusion: The Evolving Landscape of Reservation Policies

- Impact of the Ruling: The Supreme Court’s decision marks a significant shift in the interpretation of reservation policies, allowing for greater flexibility in addressing intra-group disparities within the SC community.

- Ongoing Debate: The debate over the homogeneity of SCs, the potential introduction of a creamy layer exclusion, and the appropriate criteria for sub-classification will likely continue to shape India’s reservation policies in the years to come.

- Balancing Equity and Representation: The challenge for the government and judiciary will be to balance the principles of equity and representation, ensuring that the benefits of reservation reach those who are most in need without diluting the overall objectives of social justice.

Associated Article

https://universalinstitutions.com/supreme-court-ruling-on-sc-st-quotas/

Mains UPSC Question

GS 2

Discuss the implications of the Supreme Court’s recent ruling that permits sub-classification of Scheduled Castes for reservation purposes. How does this decision relate to the debate on the homogeneity of SCs and the possible introduction of a creamy layer exclusion? (250 words)