Not just a case about improving investigation

Relevance

- GS Paper 2: Government Policies and Interventions for Development in various sectors and Issues arising out of their Design and Implementation.

- Tags: #Policereforms #SupremeCourt #UPSCMains2024 #TheHinduEditorial

Why in the News?

The recent Supreme Court ruling highlights the need for a consistent and dependable code of investigation to ensure that the guilty are not acquitted due to technicalities. The Court identified issues in the investigation process and echoed previous recommendations for police reforms.

Supreme Court Emphasizes the Need for a Reliable Investigation Framework

- In the recent case of Rajesh & Anr. vs The State of Madhya Pradesh, the Supreme Court of India underscored the importance of establishing a consistent and dependable code of investigation to prevent the escape of the guilty due to technicalities.

- While setting aside the convictions of three accused persons involved in murder and related offenses, the court exposed several illegalities in the investigation process.

- This decision aligns with the recommendations of the Justice Malimath Committee on Criminal Justice System Reforms and the Law Commission of India’s Report number 239.

Varied interpretations

Police Custody and the Indian Evidence Act

- The Supreme Court highlighted an issue concerning Section 27 of the Indian Evidence Act, which deals with when evidence obtained from a person in police custody is admissible.

- The Court suggested that a person isn’t considered in police custody until they’re formally arrested and accused in the First Information Report (FIR).

- However, this interpretation seems to be incorrect.

- Even before formal arrest, if a person is under the control or influence of the police, evidence obtained from them may still be admissible in court.

Re: Man Singh Case (1959)

- In the case of In Re: Man Singh (1959), the court clarified that ‘custody’ doesn’t always mean being locked up; it can also include being under the control or surveillance of the police.

- Even when suspects are not directly detained, if they are being watched or controlled by the police, it can be considered ‘police custody.’

- This interpretation was reaffirmed in cases like Chhoteylal vs State of U.P. (1954).

- So, in simple terms, ‘police custody’ can mean being closely monitored or controlled by the police, not just when you’re physically detained by them.

Understanding ‘Accused of Any Offence’ and ‘Custody’ in Indian Evidence Act

- In the case of State Of U.P. vs Deoman Upadhyaya (1960), the court clarified that the phrase “accused of any offence” describes the person against whom evidence, related to information given by them, can be used under this law.

- It doesn’t require the person to be formally accused when they provide the information; it’s enough if they become an accused person by the time this information is presented in court.

- In Dastagiri vs State (1960), the court emphasized that the person doesn’t have to be labeled as an accused in the First Information Report (FIR) when they share information.

- Sometimes, the information provided by a suspect (not initially accused in the FIR) might be the first piece of evidence that leads to their arrest.

- Therefore, ‘custody’ under Section 27 of the Indian Evidence Act doesn’t necessarily mean being formally arrested by the police.

- It can also include cases where information provided by someone eventually leads to their arrest.

Significance of Compliance with Sections 100(4) and 100(5) in Evidence Act

- The court placed significant importance on compliance with Sections 100(4) and 100(5) of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC) concerning the presence of independent witnesses during the search and seizure of certain items, like the body of a deceased person, their clothes, or the murder weapon.

- However, in the case of Musheer Khan@Badshah Khan & Anr vs State Of M.P. (2010), the court clarified that the value of evidence obtained under Section 27 of the Indian Evidence Act isn’t diminished solely due to non-compliance with Sections 100(4) or 100(5) of the CrPC.

- The reason behind this distinction is that Section 100 deals with procedures that compel the production of items through search, which is quite different from the voluntary information shared by an accused in custody that leads to a discovery.

- These two situations are separate, so the safeguards in search proceedings based on compulsion can’t be applied to voluntary discoveries.

- The court expressed similar views in State (NCT of Delhi) vs Sunil (2001).

- These witness statements, called panchnamas, are usually created by the police as a precaution, rather than due to a strict legal requirement.

- In simpler terms, while compliance with search and seizure procedures is important, it doesn’t necessarily affect the reliability of evidence obtained through voluntary information shared by a person in custody during a discovery process.

Separation of investigation

Reforming Police Investigations: A Balanced Perspective

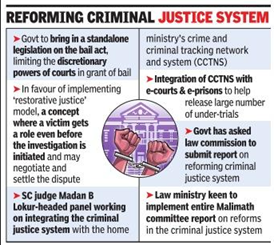

- The Court, while referencing the Justice Malimath Committee and Law Commission Reports, expressed concern about the subpar quality of police investigations, attributing low conviction rates partly to inadequate and unscientific police work.

- It’s clear that investigations must improve, and the police should adopt advanced scientific methods.

- However, the Court also emphasized the need to assess the progress made by the police following recommendations from various committees.

- The Malimath Committee suggested separating the investigation and law and order functions within the police, but this alone may not be a magic solution for better investigations.

- The Court urged a comprehensive review of the efforts made by states in implementing reforms before placing the entire blame on the police.

Improving Investigations in Cases against Influential Public Figures

- In Law Commission Report number 239, which stemmed from the case Virender Kumar Ohri vs Union of India, concerns were raised about the slow pace and effectiveness of investigations in cases involving influential public figures.

- The report highlighted issues like understaffed police stations, insufficient priority for crime investigation, and the lack of ongoing training for investigators.

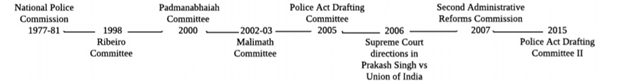

- It not only mentioned a previous recommendation for separating investigation from law-and-order duties but also emphasized the directions of the Supreme Court in the Prakash Singh & Ors. vs Union of India case in 2006.

Separating Police Duties for Quicker, More Expert Investigations

- Prakash Singh, former Director General of Police (DGP), Uttar Pradesh, former DGP, Assam and former Director General of the Border Security Force, reviewed recommendations from previous commissions and committees.

- One significant directive from the Court was to separate the tasks of investigation and maintaining law and order.

- This separation would lead to faster and more expert investigations and improved relations with the public.

- Initially, this separation was to be implemented in larger towns with populations of 10 lakh or more and then gradually extended to smaller towns.

- The idea is to divide police responsibilities to make investigations more efficient and effective, especially in bigger cities.

Progress in Implementing Police Reforms in India

- Prakash Singh’s book, “The Struggle for Police Reforms in India” (2022), reveals that 17 Indian states have taken steps to separate police functions related to investigation and law and order, as directed by the Court.

- The remaining states, while not opposing the directive, have yet to initiate the necessary steps for separation.

- However, the compliance with all 7 directives varies.

- 9 states are categorized as “good and satisfactory” in their efforts, while 20 states fall into the “average and poor” category.

- Most states have made provisions in their State Police Act or issued administrative orders to comply with the directives.

- A common challenge is the lack of additional manpower for separating these functions, except in major cities like Delhi and Mumbai.

- In some cases, like Madhya Pradesh, the directive to design a code of investigation hasn’t been fully implemented due to a lack of dedicated investigative staff.

Urgent Need for Effective Police Reforms

- Existing codes of investigation in Indian states undergo periodic revisions, including Supreme Court instructions where needed.

- However, a shortage of investigating officers hampers their skill development.

- Mere rule provisions won’t suffice for police reforms.

The Supreme Court should proactively require every state and union territory to fully comply with its directives on investigations and other matters. Additionally, the court must maintain consistency in its rulings, unless it has strong reasons to overturn earlier judgments. This would ensure a more comprehensive and effective approach to police reform.

Source: The Hindu

Mains Question

Evaluate the role of police investigation and the need for reforms in India’s criminal justice system. Discuss the recommendations made by the Justice Malimath Committee and the Law Commission of India regarding police investigations.