Neither the right to privacy nor the right to information.

Relevance:

GS Paper-3

Science and technology- Developments in Science and Technology, applications of scientific developments in everyday life, effects of scientific developments in everyday life.

Context:

The Digital Personal Data Protection Bill 2023 makes the government less transparent to the people and ends up making them transparent to both the government and private interests.

The Bill:

- Personal data bill will boost the digital economy, says Nasscom.’ This industry response to the Digital Personal Data Protection (DPDP) Bill 2023 which was introduced in Parliament reveals the real purpose of the Bill — legalising data mining rather than safeguarding the right to privacy.

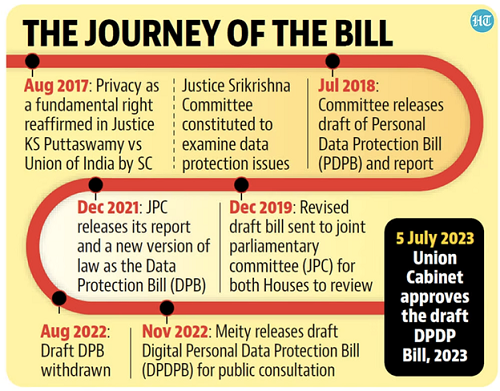

- The right to privacy was reaffirmed by a nine-judge Constitutional bench of the Supreme Court in 2017.

- The right to information provides us access to government documents to ensure transparency and accountability of the government.

- Enacted as a law, the Right to Information Act (RTI) 2005 has played a critical role in deepening democratic practices.

- The much-awaited DPDP Bill 2023 ends up undermining our right to information, without doing much to protect our right to privacy.

How does DPDP Bill 2023 Undermine the Right to Information and Right to Privacy?

- Section 8(1)(j) of the RTI Act 2005 grants exemption from disclosure if the information sought relates to personal information, unless a public information officer feels that larger public interest justifies disclosure.

- The DPDP Bill 2023 suggests replacing Section 8(1)(j) with just “information which relates to personal information”. It will undermine the RTI Act 2005. For example, the current requirement for public servants (including judges and IAS) to disclose their immovable assets will no longer apply.

- This is indeed “information related to personal information”, but it serves a larger public interest (for example, to identify public servants with disproportionate assets).

Tensions between RTI and Right to Privacy:

- Broadly, the two rights complement each other as the RTI seeks to make the government transparent to citizens, while the right to privacy is meant to protect them from government (and increasingly, private) intrusions into their lives.

- Yet, there are some tensions between the RTI and the right to privacy. For example, under the MGNREGA, mandatory disclosure provisions are meant to ensure that workers can monitor expenditure and also facilitate public scrutiny through social audits.

- Everyone has access to data about individuals registered under the Act, including when and how much was paid to each worker.

- The flip side of this, that has become apparent in recent times, is that unscrupulous operators can monitor, even scrape data systematically, depriving workers of their hard-earned wages. For example, showing up at their doorstep with offers of lucrative ‘savings or ‘insurance’.

Government and private entities can still access data citing ‘lawful purposes’-

- The Bill provides for the processing of digital personal data in a manner that recognises both the right of individuals to protect their personal data and the need to process such data for lawful purposes.

- The Bill defines “lawful purposes” in the broadest possible manner as “any purpose which is not expressly forbidden by the law”.

Undermining the Right to Information:

- The Right to Information Act 2005 anticipated some of these tensions and the consequent need to limit its own reach.

- Therefore, Section 8 of the RTI 2005 listed situations where “exemption from disclosure of information” would be granted.

- Section 8(1)(j) grants exemption from disclosure if the information which relates to personal information sought has no relationship to any public activity or interest, or which would cause unwarranted invasion of the privacy of the individual, unless a public information officer feels that larger public interest justifies disclosure.

- It set a high benchmark for exemption – information which cannot be denied to the Parliament or a State Legislature shall not be denied to any person.

- The DPDP Bill 2023 suggests replacing Section 8(1)(j) with just “information which relates to personal information”. This will undermine the RTI 2005.

Concerns Around the Bill:

- Exemption Powers to Centre: According to the Bill, the central government will have the right to exempt “any instrumentality of the state” from adverse consequences citing national security, relations with foreign governments, and maintenance of public order, etc.

- Fear of Online Censorship: The Bill also states that if an entity is penalised on more than two instances, the central government, after hearing the entity, can decide to block their platform in the country.

This is a new addition to the measure, which was not present in the 2022 draft. The proposal could add to the pre-existing online censorship regime already administered under Section 69 (A) of the Information Technology Act, 2000. The highest prescribed penalty has been capped at Rs 250 crore for not having enough safeguards against data breaches.

The Control of Central Government in Appointments-

The Chief Executive of the Data Protection Boardwill be appointed by the central government, which will also determine the terms and conditions of their service. This means the Board, an oversight body, will be under the boot of the government as the chairperson and members are to be appointed by the central government, making the watchdog less effective.

No Discussion Around Restricting Data Collection-

- In Europe, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) set a high standard for data protection.

- For instance, in France, the data protection regulator was able to fine Google €50 million for violation of policies related to consent.

- Still, there is a real danger of GDPR becoming a “paper tiger”, because the problem isn’t data protection, but data collection. Restricting data collection is not even being discussed in the new Bill.

Ignoring social, political and legal context-

- The DPDP 2023 suffers from other shortcomings. For instance, the Data Protection Board, an oversight body will be under the boot of the government as the chairperson and members are to be appointed by the central government. The DPDP Bill 2023 attempts to pass off a lame-duck as a watchdog.

- In Europe, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) set a high standard for data protection. It has a strong watchdog that operates in a society with universal literacy, and high digital and financial literacy. Restricting data collection is not even being discussed in India.

Conclusion:

A weak board combined with the lack of universal literacy and poor digital and financial literacy, as well as an overburdened legal system, mean that the chances that citizens will be able to seek legal recourse when privacy harms are inflicted on them are slim.