Meeting India’s carbon sink target

Context:

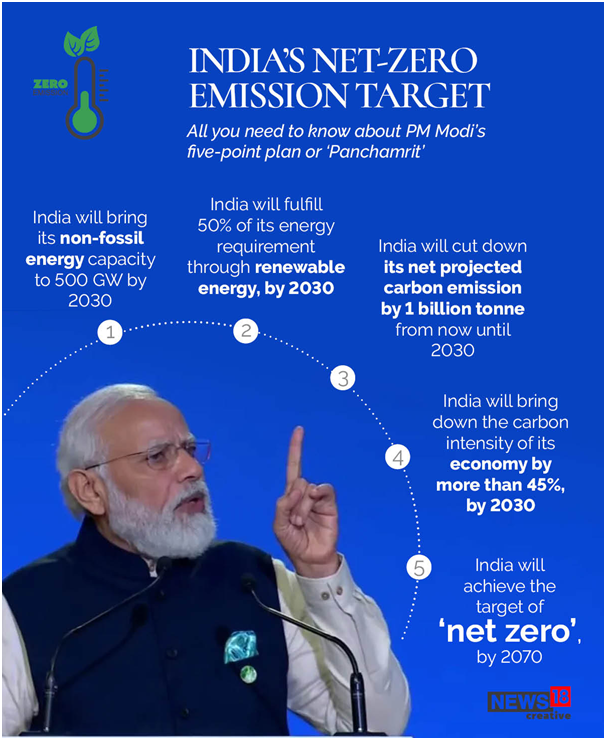

- In August last year, India updated its international climate commitments — first made in 2015 in the run-up to the Paris climate conference, it enhanced two of the three original targets it had promised to achieve by 2030.

- It said it would reduce the emissions intensity of its economy — emissions per unit of GDP — by 45 per cent from 2005 levels instead of the 33 to 35 per cent promised earlier.

- It would ensure that renewables formed at least 50 per cent — up from the original 40 per cent — of its total installed electricity generation capacity.

- The third target — a commitment to increase its carbon sink by 2.5 to 3 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent by 2030 through the creation of additional forest and tree cover — was left untouched.

- Government figures in 2022 showed that in the six years since 2015, the carbon sink in the country — which is the total amount of carbon dioxide absorbed by and residing in forests and trees — had increased by 703 million tonnes of CO2 equivalent, or roughly by 120 million tonnes every year. At this pace, the target of 2.5 to 3 billion tonnes of CO2 equivalent was unlikely to be met by 2030.

The Missing baseline year

- The carbon sink target had not been defined precisely in 2015. India had committed “to create an additional carbon sink of 2.5 to 3 billion tonnes of CO2 equivalent through additional forest and tree cover by 2030”, but it had made no mention of the baseline year.

- By distinction, India’s target on emissions intensity specified 2005 as the baseline year.

- And the commitment on renewable capacity did not require a baseline because it was an absolute target.

- The climate targets had been announced in a hurry ahead of the 2015 climate change conference because these were considered crucial to the finalisation of the Paris Agreement.

- India’s original targets on emissions intensity and renewable capacity were quite modest, and thus easy to define precisely.

- But the carbon sink target required a detailed study, which could not have happened in a short time.

- In an analysis published in 2019 Forest Survey of India (FSI) pointed out that even the word “additional” in the Indian commitment could be interpreted in different ways.

- It could mean:-

- (i) over and above the carbon sink that existed in the baseline year, or

- (ii) over and above what it would be in the target year of 2030 in the business-as-usual scenario.

- It could mean:-

- India’s forests and tree cover had a carbon sink of 29.38 billion tonnes of CO2 equivalent in 2015, and this was projected to increase in a business-as-usual scenario — that is, without the intervention of any fresh effort — to 31.87 billion tonnes in 2030, according to the FSI analysis.

- The first interpretation of “additional” (over and above the baseline year) would mean India’s target would be met if the carbon sink in 2030 was in the range of 31.88 to 32.38 billion tonnes of CO2 equivalent.

- In the second interpretation (over and above the target year), the target would be between 34.37 and 34.87 billion tonnes of CO2 equivalent.

Persisting ambiguity

- Last year, the government appeared to remove the ambiguity regarding the baseline year for the carbon sink target by committing itself to the baseline of 2005.

- In a written reply to a Parliament question Environment Minister said, “India had already achieved 1.97 billion tonnes of additional carbon sink as compared to the base year of 2005.”

- He added that “the remaining target can be achieved by increasing forest and tree cover of the country through implementation of various central and state sponsored schemes”.

- This announcement of 2005 as the baseline suddenly brought the carbon sink target within easy reach.

- India was well within its right to select 2005 as the baseline year. Under the Paris Agreement, countries themselves are supposed to set their climate targets, and this includes the choice of baseline year.

- Additionally, as mentioned earlier, India’s emissions intensity target also has 2005 as the base year. Several other countries, including the United States, use 2005 as the baseline year for their commitments.

- The statement in Parliament also seemed to settle the question of additionality flagged by the FSI analysis.

- The promised addition to carbon sink would have to be measured against what existed in the baseline year (2005) and not what it was projected to be in the target year (2030) in the business-as-usual scenario.

- This is not unusual. Additionality is measured in most cases from the baseline year.

- But just 10 days after the Parliament reply, when India formally made a submission of its updated international climate commitments to the UN climate body.There was no mention of the baseline year in India’s formal submission.

While statements in Parliament are considered the official government position, internationally, India can only be held accountable to what is contained in its official submission to the secretariat of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change.

As of now, this seems to be a minor inconsistency, and does not appear to reflect any desire to change the baseline year in future.

| Practice Question

1. What are Panchamrit goals? Critically Evaluate the current position of each goal |