INDIAN ARCHITECTURE

Introduction

The term ‘architecture’ has its roots in the Latin word ‘tekton,’ denoting a builder. The emergence of the architectural discipline aligned with early humans constructing shelters for their dwelling. In contrast, ‘sculpture’ originates from the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root ‘kel,’ signifying ‘to bend.’ Sculptures, whether fashioned by hand or with tools, constitute small works of art that emphasize aesthetics over engineering precision and measurements.

Indian Architecture

India’s architectural panorama weaves a complex tapestry, seamlessly integrating diverse styles and traditions that mirror the nation’s rich history, culture, and religion. Notable architectural styles include Hindu temple architecture, Indo-Islamic architecture, Rajput architecture, Mughal architecture, South Indian architecture, and Indo-Saracenic architecture. Remaining instances of early Indian architecture showcase the artistry of rock-cut structures, encompassing Buddhist, Hindu, and Jain temples.

The architecture of Hindu temples is marked by a distinct division between the Dravidian style prevalent in southern India and the Nagara style dominant in the north, complemented by various regional adaptations. The era of the Mughal Empire is venerated as the pinnacle of Indo-Islamic architecture, epitomized by the Taj Mahal, an iconic masterpiece symbolizing their architectural prowess. The British colonial period saw the infusion of European styles such as Neoclassical, Gothic Revival, and Baroque, leaving an enduring impact on India. The fusion of Indo-Islamic and European architectural elements gave rise to a distinctive style known as the Indo-Saracenic style.

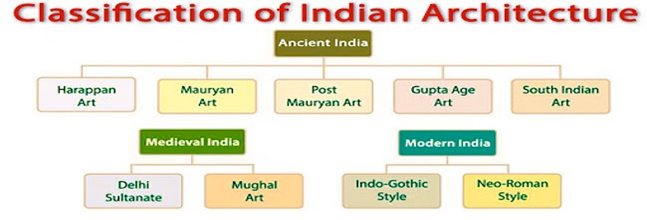

Classification of Indian Architecture

The evolution of INDIAN ARCHITECTURE has undergone diverse phases. Initially, constructions in India were crafted from wood, later transitioning to the use of bricks. A limited number of these ancient structures, particularly those made of wood, still endure today, mainly due to the challenging environmental conditions in India.

Subsequently, stone architecture emerged in the southern regions around the sixth century BC. Indian architects rapidly refined their expertise in the intricate craft of carving and constructing stone structures. By the seventh century AD, substantial and noteworthy edifices were commonly erected from stone, many of which endure in India to the present day.

Indus Valley Civilization

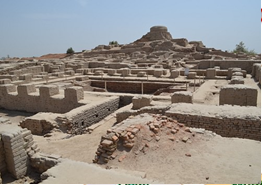

- The earliest cultural development in the Indian subcontinent, identified as the Indus Valley Civilization, can be traced back to the Chalcolithic period (3300-1300 BCE). Predominantly situated in present-day India and Pakistan, numerous archaeological sites from this historical era have come to light.

- Around 2600 BCE, the significant cities of Harappa and Mohenjodaro emerged along the banks of the Indus River in the Sindh and Punjab provinces of Pakistan. The excavations carried out in the 19th and 20th centuries provided crucial archaeological insights into various aspects of the civilization, encompassing its architecture, technology, art, trade, transportation, writing, and religion.

Features of the Indus Civilization

Distinctly Indigenous Architectural Style:

- The architectural style of the Indus Valley Civilization stood out as distinctly indigenous, free from any discernible influence from foreign sources.

Emphasis on Utilitarian Construction:

- The construction of buildings was primarily guided by utilitarian considerations, prioritizing functionality over aesthetic appeal.

Independent Evolution of Architecture:

- In contrast to prevalent trends where architecture and sculpture evolve together, the Indus Valley architecture took a unique path of independent evolution.

Deep Historical Roots in Local Cultures:

- Architectural practices were deeply embedded in local cultures, with historical ties extending over thousands of years to the earliest farming and pastoral communities.

- Notably, houses were erected on expansive platforms crafted from mud bricks.

Excellence in Urban Planning:

- The hallmark of Indus Valley architecture lay in its sophisticated approach to town planning, surpassing that of other contemporary civilizations.

Prominent Town Planning Features:

Utilitarian Focus in Urban Design:

- Harappans introduced an innovative concept of worker welfare by establishing separate quarters, a pioneering idea with lasting relevance in modern welfare states.

Strategic Fortifications:

- Fortifications were a common feature across Indus Valley sites, strategically designed to ensure the security of citizens against potential threats.

Varied Layouts of Harappan Cities:

- While the plans of Harappan cities exhibited diversity, a general pattern emerged, encompassing fortification walls, citadels, lower towns, streets, lanes, drainage systems, and water management.

Geometric Urban Planning:

- Architects utilized geometric tools to design city plans, resulting in a consistent pattern observed in numerous cities.

Arrangement of Citadel and Lower-Town:

- Harappan cities featured walled sectors, including a citadel situated on an elevated platform and a larger lower town below.

- Public structures, like the Great Bath, found their place in the citadel, while the lower town primarily housed residential buildings.

Grid-Pattern Urban Centers:

- By 2600 BCE, major cities such as Mohenjodaro and Harappa exhibited a grid of straight streets, running north–south and east–west.

Resilient Construction Strategies:

- To mitigate the risk of floods, the Harappan people constructed houses on elevated platforms, showcasing advanced disaster-proofing measures.

Drainage System:

- The Harappans demonstrated their hydraulic engineering expertise through the implementation of a highly efficient drainage system.

- These channels were designed with regularly spaced drops to facilitate self-cleaning. Private drains seamlessly interconnected with smaller conduits, guiding the city’s wastewater into larger drains that led to open areas or ponds.

- Some drains were meticulously covered with stones or large bricks, and additional features such as soakage jars and manhole cesspools were seamlessly integrated.

Reservoirs:

- The construction of reservoirs played a pivotal role in Harappan town planning, as exemplified notably in Dholavira. Prominent features included the Great Bath and wells at Mohenjodaro, numerous bath platforms and drains at Kalibangan, and rock-cut tanks and dams in Manhar and Mansar Nala at Dholavira, all designed with a focus on water conservation.

- Additionally, Banawali incorporated a moat for defense.

Water Management:

- Harappan proficiency in water management was evident in their agricultural practices. Despite relying on monsoons, they strategically constructed canals to enhance production and shield crops from adverse weather conditions.

- Various hydraulic structures, including dams, canals, and reservoirs, were uncovered at different sites. Remarkably, Lothal engineers devised an artificial dock for ship berthing.

Urban Planning Insights for Modern Challenges:

- Grid-like Patterns for Orderly Growth:

- IVC’s grid-like street patterns can serve as a model for modern urban planning, fostering systematic and planned growth to counter the disorderly construction observed in many Indian cities.

- Sanitation and Waste Management:

- Incorporating IVC’s emphasis on waste segregation and closed drainage systems could alleviate current challenges associated with inadequate sanitation networks and open drainage, thereby mitigating infectious disease risks.

- Clear Demarcation of Zones:

- Introducing IVC’s clear separation between residential and public areas into current city planning can alleviate traffic congestion.

- Efficient Use of Light and Wind:

- IVC’s architectural design, which prioritized effective use of light and wind, can inspire efforts to reduce the modern society’s carbon footprint.

- Street Planning for Dust Prevention:

- Embracing IVC’s practice of having doors open into lanes instead of roads can minimize dust and particle entry into houses due to road traffic.

- Water Conservation Strategies:

- Implementing IVC’s water conservation strategies, including tanks and ponds, in contemporary urban planning can address water scarcity issues witnessed in cities like Chennai.

Mauryan Architecture

Mauryan Architecture: A Cultural Revival

- Following the decline of the Indus Valley Civilization, India encountered a hiatus in architectural development, resorting to materials such as wood or repurposed brick. However, a renaissance in architecture blossomed during the Maurya Empire, spanning from 322 to 185 BCE. Over the ensuing centuries, Indian rock-cut architecture, primarily Buddhist, gained prominence, adorned with enlightening Buddhist sculptures.

Impact of Ashoka’s Transformation:

- Ashoka’s embrace of Buddhism marked a pivotal shift, propelling extensive Buddhist missionary activities that molded distinctive sculptural and architectural styles. This transformative period gave rise to architectural masterpieces in the forms of Stupas, Pillars, Caves, and Palaces.

Stupas Commemorating Buddha’s Triumphs:

- During the Mauryan era, particularly under Ashoka’s reign, numerous stupas adorned the Indian landscape. These solid-domed structures, crafted from brick or stone in various sizes, served as tributes to the accomplishments of Gautama Buddha.

Pillars of Dharma – Icons of Mauryan Art:

The Pillars of Dharma emerged as iconic monuments in Mauryan art, standing freely without a supportive role. Comprising two main components – the meticulously carved monolith shaft and the capital adorned with animal figures standing on stylized lotus-decorated abacuses – these pillars showcased exquisite craftsmanship.

Lion Capital – Symbolism and Mastery:

- Among the notable achievements is the Lion Capital found at Sarnath near Varanasi. Commissioned by Ashoka to commemorate Buddha’s first sermon, this masterpiece features four Asiatic lions seated back to back, symbolizing power, courage, pride, and confidence. The polished surface, embellished with chakras and symbolic animals, attests to its status as a pinnacle of Mauryan sculpture.

Cave Architecture – Subterranean Artistry:

- Complementing pillars, rock-cut caves stand as testaments to Ashoka’s artistic prowess. Examples, such as the caves at Barabar Hill and Nagarjuni Hill, including the Sudama Caves, showcase intricate designs. Ashoka’s benevolence is evident in the Barabar caves donated to Ajivika monks and the Nagarjuni caves contributed by Dasharatha. The Gopika Cave, with its mirror-like polished interior, reflects the sophistication of Mauryan cave architecture.

- Mauryan architecture, shaped by Ashoka’s Buddhist patronage, has left an indelible imprint on India’s cultural and artistic heritage. The monumental stupas, iconic pillars, and meticulously crafted cave structures stand as enduring symbols of this remarkable cultural resurgence.

Magnificence and Grandeur: Mauryan Palaces Unveiled

- In the era of the Mauryan Empire, palaces were distinguished by opulent features. Gilded pillars embellished with golden vines and silver birds adorned these structures. Surrounding the towns, meticulous fortifications comprised towering walls with battlements. The water ditches enveloping the palaces showcased artistic details, including depictions of lotuses and diverse plants.

Post Mauryan Architecture

Architectural Evolution: Post-Mauryan Era

- Following the decline of the Mauryan Empire, several smaller dynasties ascended to prominence, significantly influencing the architectural landscape. In the north, the Shungas, Kanvas, Kushanas, and Shakas wielded influence, while in the southern and western regions of India, the Satvahanas, Ikshavakus, Abhiras, and Vakatakas rose to prominence.

Continuity of Architectural Heritage:

- The enduring legacy of rock-cut caves and stupas persisted, with each dynasty contributing its unique characteristics. Concurrently, diverse schools of sculpture flourished, reaching their pinnacle during the post-Mauryan period.

Evolution of Rock Caves:

- The construction of rock caves, integral to Mauryan architecture, continued. However, the post-Mauryan era witnessed the emergence of two distinct types of rock caves – Chaitya and Viharas. Chaitya, featuring a rectangular prayer hall with a central stupa, served as a space for prayer, while Viharas functioned as residential quarters for monks.

Stupas: Magnificence and Transformation:

- Stupas underwent significant transformations in the post-Mauryan period, growing both larger and more ornate. This marked a departure from the prevalent use of wood and brick, with stone becoming the primary construction material.

Emergence of Sculptural Schools:

- During the post-Mauryan era, three prominent sculptural schools thrived in different regions of India – Gandhara, Mathura, and Amravati. These schools showcased distinctive styles and artistic expressions, contributing to the rich and diverse cultural tapestry of the period.

Rock-cut Architecture:

- Rock-cut architecture stands as a testament to human creativity, demonstrating the ability to carve structures, buildings, and sculptures from solid rock in its natural environment. This architectural form gained prominence across civilizations, particularly in the construction of temples, tombs, and cave dwellings. Among the earliest instances of rock-cut architecture is the Barabar Caves in Bihar, India, dating back to the 3rd Century BC.

Harmony with India’s Landscape:

- The abundant rocky mountains in India provided an ideal backdrop for the marvels of rock-cut architecture. Structures carved from stone exhibited remarkable durability, standing resilient against the tests of time.

Evolution of Rock-cut Architecture in India: The evolution of rock-cut architecture in India unfolds in distinctive phases:

Early Buddhist Architecture (2nd Century BC to 2nd Century AD):

- Attributed to Ashoka and his grandson Dasaratha, early Buddhist rock-cut caves featured chaityas and viharas, initially constructed with wood.

- Notable examples from this era include Karla, Kanheri, Nasik, Bhaja, and Bedsa, along with the iconic Ajanta caves.

Transition Phase (5th Century AD):

- The 5th century AD marked a pivotal transition, marked by the abandonment of timber and the incorporation of the Buddha’s image as a central element in architectural design.

- Viharas underwent a metamorphosis, with inner cells, once occupied solely by monks, now adorned with the image of the Buddha.

Dravidian Rock-cut Style (Later Periods):

- The Dravidian rock-cut style emerged as a dominant phase, featuring distinctive elements like mandapas and rathas.

- Mandapas, open pavilions carved from rocks, took the form of simple columned halls with cells at the back wall.

- Rathas, monolithic shrines carved from a single rock, showcased the pinnacle of craftsmanship in rock-cut architecture.

The evolution of rock-cut architecture in India narrates a story of adaptability and artistic prowess across centuries. From the early Buddhist period to the Dravidian rock-cut style, each phase adds a unique chapter to India’s architectural heritage, with tales etched in the enduring embrace of solid rock.

Significant Rock-cut Caves

Rock-cut caves hold immense historical and architectural significance, and some notable examples are crucial from an examination perspective:

Kanheri Caves:

- Located near Mumbai.

- Encompasses the period from the 2nd to the 9th century AD.

- Belongs to the Hinayana phase of Buddhist architecture, with later Mahayana additions.

- Approximately 100 caves, featuring a 5th-century image of Buddha.

Jogeshwari Caves:

- Situated within the Salsette Island.

- Represents the later stages of Mahayana Buddhism.

- Accommodates Brahmanical shrines.

- Constructed in the second half of the 8th century.

Montpezir (Mandapeswar Caves):

- Also known as Mandapeswar caves, near Mumbai.

- The only Brahmanical caves converted into a Christian shrine.

- Features three caves dating back to the 8th century.

Karla Caves:

- Located on Banaghta hills near Mumbai.

- Belongs to the Hinayana period of Buddhist architecture.

- Houses one of the largest and best-preserved chaityas in the country.

- Main cave, Great Chaitya cave, dates back to 120 CE.

Bhaja Caves:

- Situated near Pune.

- Excavated around the 2nd century BC.

- Associated with Hinayana Buddhism in Maharashtra.

- Noteworthy for indications of wooden architecture, featuring carvings of musical instruments.

Bedsa Caves:

- Located near Pune.

- Chaitya resembles the great hall at Karle but on a smaller scale.

- Features four pillars with carvings of horses, bulls, and elephants.

Ellora Caves:

- One of the largest rock-cut temple complexes globally, located in Maharashtra.

- Features Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain monuments dating from 600–1000 CE.

- Cave 16 showcases the Kailash temple, the largest monolithic rock excavation globally.

Ajanta Caves:

- Carved out of flood basalt rock in the Sahyadri ranges near Aurangabad.

- Comprises a total of 29 caves dedicated to Buddhism.

- Developed between 200 BCE to 650 CE.

- Features murals depicting Jataka stories and reflects two construction phases.

Elephanta Caves:

- Situated in Mumbai.

- Belongs to the 8th century AD.

- Ganesh Gumpha is an early example of Brahmanical temple architecture.

- Notable sculptures include Ravana shaking Kailasa and the Trimurti.

Udaygiri Caves:

- Located in Madhya Pradesh.

- Contains some of the oldest surviving Hindu temples and iconography in India.

- Associated with Gupta period monarchs from its inscriptions.

- Twenty caves with iconography of Vaishnavism, Shaktism, and Shaivism.

These rock-cut caves serve as invaluable treasures, preserving diverse architectural styles and religious iconography, providing a window into India’s rich cultural heritage.

Pallavas’ Impact on Rock-cut Architecture:

- The Pallavas, an influential ancient dynasty that reigned over a substantial part of Southern India from the 6th to the 9th centuries AD, left an enduring legacy with their profound contribution to rock-cut architecture. Kanchipuram, their capital, served as the nucleus of their rule, with the Pallavas gaining acclaim for introducing the distinctive Dravidian style of temple architecture.

- Within the realm of rock-cut architecture, the Pallavas showcased unparalleled artistic prowess, most notably reflected in the iconic monuments of Mahabalipuram. Designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, Mahabalipuram stands as a living testament to the evolving styles mastered by the Pallavas.

Key Contributions in Mahabalipuram:

Evolution from Cave Temples to Monolithic Shrines:

- The Pallava shrines embarked on their journey as rock-cut cave temples, gradually transitioning into monolithic shrines meticulously carved out of colossal rocks. This evolution reached its zenith with the creation of “structural temples,” meticulously constructed from the ground up.

- Distinctive Features in Rock-cut Shrines:

- Multiple rock-cut shrines featuring cave-like verandahs or mandapas adorned with rows of intricately carved pillars.

- Pillars, often embellished with carved lions at their bases, became a signature feature synonymous with Pallava architecture.

- Detailed Narrative Panels:

- Pillars and walls adorned with intricate panels narrating episodes from Hindu mythology, embodying the Pallavas’ commitment to storytelling through art.

- Niches inside the caves served as abodes for sculpted deities, contributing to the spiritual and aesthetic ambiance of the shrines.

- Varied Depictions:

- The Varaha Mandapa in Mahabalipuram stands out with stunning carvings depicting stories of Varaha, the boar incarnation of Lord Vishnu.

- The Mahishamardini Mandapa is a dedicated space for Mahishamardini, a form of Goddess Durga, while the Trimurti Mandapa honors the trinity of Lord Brahma, Lord Vishnu, and Lord Shiva.

- Magnificent Krishna Mandapa:

- The Krishna Mandapa, a pinnacle of Pallava rock-cut architecture, features a spectacular panel known as Govardhanadhari. This panel portrays Lord Krishna lifting the mythical Govardhana hill to shield his village from relentless rains.

The Pallavas’ legacy in rock-cut architecture not only reflects their aesthetic brilliance but also stands as a historical and cultural treasure, inviting admiration for its beauty and the exceptional skills demonstrated by the artists of that era.

| Comparison of Art Forms at Ellora and Mahabalipuram

Stylistic Similarities:

Distinct Features:

While sharing stylistic similarities rooted in Hindu mythology and rock-cut traditions, Ellora and Mahabalipuram also boast unique features, from geological distinctions to the diversity of religious representations and carving techniques, contributing to their individual artistic identities. |

Gupta Architecture

- In the epoch of the Gupta dynasty, temples emerged as the preeminent architectural wonders, showcasing intricate carvings depicting various Gods, particularly avatars of Vishnu and Lingams, alongside representations of Goddesses. In the initial stages of Gupta temple construction, the Shikhara did not take a central role but gradually gained prominence in the later Gupta era. Typically characterized by a single entrance, mandapa, or porch, these temples exuded a distinctive charm.

- The Gupta-style temple architecture drew inspiration from the norms of the Mathura school.

- Eminent examples include the Sanchi temple at Tigwa, featuring a flat roof, the Dasavatar Temple at Deogarh, the Bhitargaon temple, and the Mahadev Temple at Nachna Kuthar, all boasting a square tower of Shikhara. Another noteworthy structure is the circular Manyar Math at Rajgriha, offering a unique glimpse into Gupta-era temple design. The prevalent architectural style during the Gupta period was the Nagara style.

- Although often associated with Gupta style, the Ajanta, Elephanta, and Ellora caves were crafted under the influence of other dynasties in Central India. Nevertheless, they bear the hallmark of Gupta architectural finesse, characterized by monumentality and balance.

Ajanta Caves:

- The Ajanta Caves, hewn into a 75-meter rock wall, stand as ancient monasteries and worship halls embodying diverse Buddhist traditions. Adorned with paintings narrating the past lives and rebirths of the Buddha, along with pictorial tales from Aryasura’s Jatakamala, these caves also feature rock-cut sculptures portraying Buddhist deities.

Ellora Caves:

- Ellora, designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in Maharashtra, stands as one of the most expansive rock-cut monastery-temple cave complexes globally. Dating from the 600–1000 CE period, Ellora encompasses Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain monuments and artworks. Notably, Cave 16 hosts the Kailasha temple, the largest single monolithic rock excavation globally, designed in the shape of a chariot and dedicated to Lord Shiva.

Udayagiri Caves and Dashavatara Temple:

- The Udayagiri Caves offer insights into connections with the Gupta dynasty and its ministers. Meanwhile, the Dashavatara Temple at Deogarh, a venerable structure surviving from early times, showcases important sculptural works.

Temple Architecture

- As humanity cultivated a deep respect and awe for the forces of nature, the tradition of worshiping these forces took shape. The concept of ‘god’ manifested in human consciousness as people personified these natural forces. Gods, depicted in human forms, found their abode in structures known as temples. The development of temple architecture in India unfolded across diverse regions, with geographical, climatic, ethnic, racial, historical, and linguistic factors frequently influencing the unique styles of these temples.

Early Temples in India:

- In the initial phases of the Vedic era, explicit mentions of temples are scarce.

- Worship and rituals primarily revolved around the holy fire, known as ‘yajnas.’ However, in the later stages of the Vedas, alongside ceremonial fire rituals, the practice of idol worship emerged.

- These idols initially found a place in rudimentary structures, possibly beginning with basic earth mounds and later evolving into brick constructions with thatched roofs.

Early temples in India, predating the emergence of distinctive architectural styles, can be categorized into three types:

- Sandhara Type (without Pradikshinapatha)

- Nirandhara Type (with Pradakshinapatha)

- Sarvatobhadra (accessible from all sides)

Prominent temple sites from this period include Deogarh in Uttar Pradesh, Eran, Nachna-Kuthara, and Udaygiri near Vidisha in Madhya Pradesh. These temples exhibit simple structures comprising a veranda, a hall, and a shrine located at the rear.

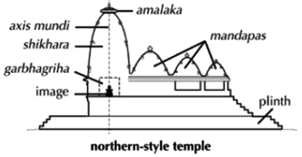

Structural Elements of Hindu Temples:

The foundational structure of a Hindu temple integrates the following components:

- Sanctum (Garbhagriha): Initially a compact cubicle with a single entrance, the Garbhagriha, or ‘womb-house,’ progressively evolved into a more expansive chamber. Its purpose is to house the central icon, serving as the focal point for various ritual activities.

- Entrance: Whether in the form of a portico or a colonnaded hall known as a mandapa, the temple entrance provides space for a diverse congregation of worshippers.

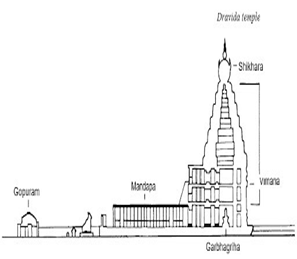

- Spire: Freestanding temples typically boast a spire resembling a mountain. In North India, it may take the form of a curving shikhar, while in South India, it manifests as a pyramidal tower known as a vimana.

- Vahana: Positioned strategically in line before the sanctum, the Vahana symbolizes the mount or vehicle of the temple’s primary deity. It is accompanied by a standard pillar or dhvaj. Two primary temple styles are recognized—Nagara in the north and Dravida in the south. Some experts acknowledge the Vesara style, emerging from the selective fusion of Nagara and Dravida elements, as a distinct architectural style.

Iconography of Indian Temples:

- The scrutiny of deity images falls within the realm of art history known as ‘iconography.’ This field involves identifying images based on specific symbols and associated mythologies. Each region and era has given rise to unique styles of images with regional variations in iconography.

- The placement of deity images within a temple is meticulously planned. For instance, river goddesses like Ganga and Yamuna are commonly positioned at the entrance of a Garbhagriha in a Nagara temple, while Dvarapalas (doorkeepers) are often situated on the gateways or gopurams of Dravida temples. Erotic images (mithunas), the nine auspicious planets (navagrahas), and yakshas are strategically placed at entrances for protective purposes.

- Subsidiary shrines encircling the main temple are dedicated to the family or incarnations of the principal deity. Additionally, various ornamental elements such as gavaksha, vyala/yali, kalpa-lata, amalaka, kalasha, etc., are employed in distinctive ways and locations throughout the temple.

Dravidian Temple Architecture

- The Pallavas, who exerted influence over regions in Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, and northern Tamil Nadu until the ninth century, were pioneers of the Dravidian style of temple architecture in South India. Although predominantly Shaivite, remnants of Vaishnava shrines from their era persist.

- Attributed primarily to the reign of Mahendravarman I, a contemporary of the Chalukyan king Pulakesin II of Karnataka, the early structures showcase significant architectural achievements. Narasimhavarman I, also known as Mamalla, who ascended the Pallava throne around 640 CE, is particularly celebrated for his architectural contributions.

- Key features of this style include:

- The Dravidian temple is enclosed within a compound wall.

- The front wall features an entrance gateway known as a Gopuram.

- The main temple tower, called vimana in Tamil Nadu, resembles a stepped pyramid, distinct from the curving shikhara of North India.

- In South Indian temples, the term ‘shikhara’ is reserved for the crowning element at the top, often shaped like a small stupika or an octagonal cupola—equivalent to the amalak and kalasha of North Indian temples.

- Fierce Dvarapalas (door-keepers) guard the entrance to the garbhagriha.

- Large water reservoirs or temple tanks are commonly found within the complex.

- Some of the oldest parts of sacred temples in South India feature smaller towers.

- Subsidiary shrines may either be incorporated within the main temple tower or situated separately beside the main temple.

Classification of Dravidian Temples:

- Similar to the various subdivisions of Nagara temples, Dravidian temples also have subdivisions based on different shapes: square (kuta or caturasra), rectangular (shala or ayatasra), elliptical (Gaja-Prishta or vrittayata), circular (vritta), and octagonal (ashtasra). These shapes may be combined to create unique styles in specific periods and places.

- Famous Dravidian Temples in India:

- The Brihadeshwara temple in Thanjavur, completed around 1009 by Rajaraja Chola, stands as the largest and tallest Dravidian-style temple in India.

- Other notable Dravidian temples include the Annamalaiyar Temple in Tiruvannamalai, Tamil Nadu, and the Meenakshi Temple, Tamil Nadu.

Contribution of Pallavas to Dravidian Architecture:

- In the 7th century CE, the Pallavas made a lasting impact on Dravidian architecture, creating magnificent monuments. Mahendravarman and Narasimhavarman, great patrons of art and architecture, significantly contributed to this era.

Contribution of Cholas to Dravidian Architecture:

- The Cholas further refined the Dravidian temple style inherited from the Pallavas. They transitioned from the early cave temples to using stone as the primary material, introducing elaborate Gopurams adorned with carvings representing various Puranas. The Vimanas reached greater grandeur, and sculptures gained prominence in temple construction during the Chola period. The Brihadeshwara temple’s tower, at 66 meters, exemplifies the height attained during this period.

Deccan Architecture

Diverse Influences in Karnataka:

- Temple architecture in Karnataka showcases a rich amalgamation of styles from both North and South Indian temples, resulting in a distinctive and diverse aesthetic.

Ellora’s Grand Projects:

- In the late 7th or early 8th century, Ellora’s ambitious projects evolved into grand structures, highlighting the prowess of Deccan architecture through impressive rock-cut monuments.

Rashtrakutas’ Control:

- Around 750 CE, the Rashtrakutas assumed control of the Deccan from the early western Chalukyas, marking a significant shift in regional power dynamics.

Kailashnath Temple at Ellora:

- The architectural zenith of the Rashtrakutas is the Kailashnath temple at Ellora. Carved entirely from living rock, this complete dravida structure dedicated to Shiva features a Nandi shrine, gopuram-like gateway, cloisters, subsidiary shrines, staircases, and an imposing vimana rising to thirty meters.

Vesara Architecture in Karnataka:

- Southern Deccan, especially Karnataka, witnessed the emergence of experimental hybrid vesara architecture, showcasing a fusion of various architectural elements.

Chalukyan Legacy:

- The western Chalukya kingdom, founded by Pulakesin I around 543, experienced early rock-cut caves and later structural temples. Notably, the Ravana Phadi cave at Aihole is an early example known for its distinctive sculptural style.

Pattadakal’s Elaborate Temples:

- Vikramaditya II’s reign (733-44) saw the construction of the Virupaksha temple in Pattadakal, an elaborate Chalukyan temple by chief queen Loka Mahadevi. The Papnath temple at the same site, dedicated to Lord Shiva, is also noteworthy.

Lad Khan Temple at Aihole:

- Lad Khan temple in Aihole, Karnataka, seemingly draws inspiration from hill temples with wooden roofs. However, it is uniquely constructed from stone, showcasing the inventive spirit of Deccan architecture.

Hoysaleswara Temple at Halebid:

- The Hoysaleswara temple at Halebid, built in dark schist stone in 1150 by the Hoysala king, is dedicated to Shiva as Nataraja. Featuring a double structure, it includes a spacious hall for mandapa, facilitating music and dance.

Vijayanagara Synthesis:

- Founded in 1336, Vijayanagara exemplifies the synthesis of centuries-old dravidian temple architecture with Islamic styles from neighboring sultanates. This architectural fusion stands as a testament to the cultural and artistic vibrancy of the Vijayanagara kingdom.

Nagara Style or North Indian Temple Architecture:

The Nagara style of temple architecture, revered in northern India, is characterized by distinctive features. In North India, the tradition is to construct entire temples on stone platforms with ascending steps, setting it apart from other architectural styles. Nagara temples typically avoid intricate boundary walls or gateways, and the garbhagriha (sanctum sanctorum) consistently occupies a position directly beneath the tallest tower.

Key Features of the Nagara Style:

- Stone Platform: Temples are commonly elevated on stone platforms with ascending steps.

- Absence of Elaborate Boundaries: Nagara temples usually lack intricate boundary walls or gateways.

- Garbhagriha Placement: The garbhagriha is invariably positioned directly beneath the tallest tower.

- Shikhara Shape: The shape of the shikhara (tower) varies, often supporting an Amalaka or Kalash on top.

- Examples: The Kandariya Mahadev Temple in Madhya Pradesh stands out as a prominent illustration of the Nagara style.

Classification of Nagara Style Based on Shikhara Shape:

Nagara temples are further categorized based on the shape of the shikhara:

- Rekha-Prasad or Latina: Characterized by a simple shikhara with a square base and inward-curving walls. Examples include the Sun Temple at Markhera and the Sri Jagannath Temple in Odisha.

- Shekari: A variation of the Latina style, featuring a main Rekha-Prasad shikhara with additional rows of smaller steeples on both sides. The Khajuraho Kandariya Mahadev Temple is an exemplar.

- Bhumija: Evolved from the Latina style, Bhumija temples have a flat, upward-tapering projection with a central Latina spire and miniature spires on the quadrant formed by the tapering tower. The Udayeshwar Temple in MP is constructed in this style.

- Valabhi: Rectangular temples with barrel-vaulted roofs, also known as wagon-vaulted buildings. The Teli Ka Mandir in Gwalior serves as an illustration.

- Phamsana: Shorter and broader structures with roofs rising gently like a pyramid. The Jagmohan of Konark Temple embodies the Phamsana mode.

Sub-schools of Nagara Style:

- Odisha School: Features a shikhara that rises vertically before curving inwards at the top, often with square lower reaches and circular upper portions. Notable examples include temples in Odisha.

- Chandel School: Temples are conceived as a single unit, with shikharas curving from bottom to top. Miniature shikaras rise from the central tower, as seen in Chandel temples.

- Solanki School: Similar to the Chandel School but with carved ceilings resembling a true dome. Intricate decorative motifs are a distinguishing feature.

Famous Nagara Temples in Various Regions of India:

Central India Temples

- Shared Characteristics in Construction:

- Temples across Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, and Rajasthan share a distinctive trait – they are constructed using sandstone.

- Madhya Pradesh stands as the host to some of the oldest surviving structural temples dating back to the Gupta Period.

- Distinctive Elements of Nagara Temples:

- The Gupta Period introduced unique crowning elements, the amalak and kalash, adorning the summits of all nagara temples.

- These temples, with a modest appearance, typically consist of four pillars supporting a small mandapa and a compact garbhagriha.

- Architectural Marvels: Udaigiri and Sanchi:

- Udaigiri, on the outskirts of Vidisha, and another at Sanchi near the stupa, contribute to a larger Hindu complex of cave shrines, showcasing architectural diversity.

- Deogarh: Late Gupta Period Temple:

- Deogarh in Lalitpur District, Uttar Pradesh, built in the early sixth century CE, exemplifies the late Gupta Period temple architecture.

- Following the panchayatana style, it features a rectangular plinth with four smaller subsidiary shrines, epitomizing the nagara style.

- Chausath Yogini Temple: Tantric Marvel:

- Predating the tenth century, the Chausath Yogini temple comprises small, square shrines dedicated to goddesses linked with the rise of Tantric worship.

- Built between the 7th and 10th centuries, several such yogini temples emerged across Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, and as far south as Tamil Nadu.

- Khajuraho’s Cultural Extravaganza:

- Khajuraho, known for temples devoted to Hindu and Jain deities, reflects Central India’s architectural prowess.

- The Lakshmana temple, dedicated to Vishnu, and the Kandariya Mahadeo temple in Khajuraho represent quintessential examples of temple architecture in the region.

Central India’s temples weave a captivating tapestry of sandstone splendor, blending unique Gupta Period elements, diverse architectural styles, and a cultural legacy that transcends time.

Western Indian temples

Abundance and Diversity of Temples:

- Temples in the northwestern regions of India, spanning Gujarat and Rajasthan and extending into western Madhya Pradesh, are numerous and exhibit a rich diversity in architectural styles.

Variety in Building Materials:

- The materials employed in the construction of these temples demonstrate a diverse range in color and type.

- While sandstone remains the predominant choice, certain temple sculptures from the 10th to 12th centuries showcase grey to black basalt.

Distinctive Use of Marble:

- Notably, there is a unique utilization of manipulatable soft white marble, a distinguishing feature evident in the splendid Jain temples of Mount Abu from the 10th to 12th centuries and the 15th-century temple at Ranakpur.

Significant Cultural and Historical Site – Samlaji:

- Samlaji in Gujarat emerges as a significant art-historical site in the region, making a substantial contribution to its cultural and historical tapestry.

Historical Sun Temple at Modhera:

- The Sun temple at Modhera, with its origins tracing back to the early 11th century, was commissioned by Raja Bhimdev I of the Solanki Dynasty in 1026.

Impressive Rectangular Stepped Tank – Surya Kund:

- The temple at Modhera boasts an impressive rectangular stepped tank known as the Surya Kund, acknowledged as one of the most grandiose temple tanks in India.

Celestial Alignment during Equinoxes:

- A distinctive feature of the Sun temple is its alignment with the sun during the equinoxes, establishing a celestial connection with the central shrine and enhancing the overall architectural marvel.

Eastern Indian Temples:

- Utilization of Terracotta in Bengal:

- Terracotta served as the primary construction medium in Bengal until the 7th century. It was employed to craft plaques depicting both Buddhist and Hindu deities, showcasing the rich artistic tradition of the region.

- Distinctive Ahom Architectural Style in Assam:

- Assam developed a distinctive regional architectural style known as the Ahom style. This unique approach was shaped by the migration of the Tais from Upper Burma and the influence of the Pala style of Bengal, resulting in a distinct visual identity.

- Pala Dynasty’s Impact on Bengal Temples:

- Temples in Bengal, dating back to the Pala dynasty, feature a unique architectural style influenced by the Pala rulers. This distinctive expression reflects both the historical influence of the Palas and the manifestation of the local Vanga style.

- Architectural Diversity in Odisha Temples:

- Odisha temples, categorized into rekhapida, pidhadeul, and khakra orders, exhibit vertical shikharas sharply curving inwards. Preceded by mandapas and surrounded by boundary walls, these structures contribute to the rich architectural diversity of the region.

- Ornate Carvings at Konark Sun Temple:

- The Sun temple in Konark, erected around 1240, is celebrated for its intricate ornamental carvings. Notably, the temple features twelve pairs of colossal wheels, symbolizing the chariot wheels of the Sun god and exemplifying the artistic grandeur of the era.

Hill Temples:

Distinctive Architectural Style:

- The hill regions of Kumaon, Garhwal, Himachal, and Kashmir have nurtured a unique architectural style in their temples, influenced by the rich heritage of Gandhara, Gupta, and post-Gupta traditions.

Cultural Interplay:

- This architectural synthesis reflects the historical and cultural interplay between Buddhist and Hindu traditions, fostered by the interactions of Brahmin pundits and Buddhist monks in these hilly terrains.

Blend of Design Elements:

- Temples in these regions showcase a captivating blend of design elements, harmoniously converging the rekha-prasada or latina style for the garbhagriha and shikhara. This blend is often complemented by the inclusion of pagoda-shaped structures, creating a diverse architectural landscape.

Fusion of Buddhist and Hindu Traditions:

- The structures of these temples palpably exhibit the fusion of Buddhist and Hindu traditions. The sanctity of the garbhagriha and the towering shikhara creatively integrates design motifs that resonate with both cultural influences.

Melting Pot of Diverse Practices:

- The hills, acting as a melting pot of diverse religious practices, have given rise to temple architecture that transcends individual traditions, embodying a shared heritage shaped by the coexistence of various beliefs.

Examples:

- Among the noteworthy examples is the Pandrethan temple in Kashmir, dating back to the 8th and 9th centuries. Situated on a plinth surrounded by a water tank, this temple exemplifies the distinctive architectural features of the region. Additionally, temples at Jageshwar and Champavat in Kumaon serve as significant illustrations of this unique hill temple style, preserving the rich cultural and religious history of their surroundings.

Buddhist Architectural Developments:

- Significance of Bodhgaya: Bodhgaya holds a paramount position as a Buddhist site, with profound reverence for the bodhi tree. The Mahabodhi Temple in Bodhgaya stands as a testament to the architectural achievements of that era.

- King Ashoka’s Contribution: King Ashoka’s dedication to Buddhist architecture is evident in the construction of the first shrine at Bodhgaya, located at the base of the Bodhi tree.

- Sculptural Richness in Mahabodhi Temple: The Mahabodhi Temple showcases a wealth of sculptures in its niches, dating back to the 8th century Pala Period. Although the present structure is a colonial-era reconstruction, it faithfully follows the original 7th-century design.

- Unusual Design of Mahabodhi Temple: The Mahabodhi Temple features a distinctive design, defying strict categorization as dravida or nagara. Its narrow, ascending form, reminiscent of a dravida design, sets it apart in architectural uniqueness.

- Nalanda’s Mahavihara: Nalanda, a renowned monastic university founded in the 5th century CE by Kumargupta I, comprises a complex of several monasteries. Successive monarchs contributed to the continuous expansion of this architectural marvel.

- Evolution of Nalanda Sculptures: Nalanda’s sculptural art, crafted in stucco, stone, and bronze, evolved under the influence of Buddhist Gupta art from Sarnath. Initial depictions focused on Mahayana pantheon deities, including standing Buddhas and bodhisattvas.

- Tantric Influence in Nalanda: In the late 11th and 12th centuries, Nalanda transformed into a significant tantric center. The sculpture repertoire shifted to highlight Vajrayana deities like Vajrasharada, Khasarpana, and Avalokiteshvara.

- Crowned Buddhas in Buddhist Art: The post-10th century period saw an increased prevalence of depictions featuring crowned Buddhas, marking an evolution in Buddhist artistic expressions.

- Buddhist Monasteries in Odisha: Odisha witnessed the emergence of major Buddhist monasteries, with Lalitagiri, Vajragiri, and Ratnagiri gaining prominence as noteworthy centers.

- Buddhist Presence in Nagapattinam: Nagapattinam, a significant port-town, retained its status as a major Buddhist center, continuing its influence even into the Chola Period.

Jain Architectural Achievements

- Enduring Legacy of Temple Construction: Similar to Hindus, Jains have cultivated a robust tradition of prolific temple construction, scattering their sacred shrines and pilgrimage destinations across India, with the notable exception of hilly regions.

- Ancient Pilgrimage Heritage in Bihar: The earliest Jain pilgrimage sites have deep roots in Bihar, marking the initial phases of Jain architectural endeavors.

- Architectural Marvels in Ellora and Aihole: Within the Deccan region, particularly in Ellora and Aihole, Jain builders have etched an indelible mark with some of the most architecturally significant sites, showcasing their artistic prowess.

- Central India’s Showcase of Jain Temples: Deogarh, Khajuraho, Chanderi, and Gwalior proudly exhibit excellent examples of Jain temples, contributing to the diverse tapestry of Indian architecture.

- Karnataka’s Abundance of Jain Heritage: Karnataka stands as an abundant repository of Jain heritage, hosting numerous shrines. One standout is Shravanabelagola, housing the renowned statue of Gomateshwara. This colossal granite structure, towering at eighteen meters, holds the distinction of being the world’s tallest monolithic free-standing statue. Commissioned by Camundaraya, the General-in-Chief and Prime Minister of the Ganga Kings of Mysore, this statue stands as an architectural marvel.

- Artistic Jain Temples in Mount Abu: Mount Abu’s Jain temples, credited to Vimal Shah, showcase distinctive patterns on every ceiling. The inclusion of graceful bracket figures along the domed ceilings enhances the overall artistic allure of these temples.

- Grand Pilgrimage Site in Shatrunjay Hills: Nestled in the Shatrunjay hills near Palitana in Kathiawar, Gujarat, is a grand Jain pilgrimage site boasting scores of temples clustered together, forming an imposing architectural ensemble.

Indo-Islamic Architecture

During Sulatanate Period

Architectural Varieties of the Sultanate Era:

- In the Sultanate period, architectural styles can be classified into three main categories. Firstly, there’s the Delhi or Imperial style, thriving under the patronage of Delhi Sultans and encompassing structures built by various rulers. The second category is the provincial style, fostered by regional ruling dynasties, mostly of Muslim origin. While influenced by the Imperial style, provincial architecture possessed distinctive characteristics. The third category is Hindu architecture, flourishing under the rule of Hindu kings in Rajasthan and the Vijayanagara Empire. Despite the influence of the Imperial style, Hindu architecture retained its unique features.

Turko-Iranian Influence and Provincial Architectural Styles:

- The Turks, influenced by Iranian architectural styles, preserved these characteristics upon settling in India. Muslim rulers in provinces erected palaces, tombs, forts, and mosques, drawing inspiration mainly from the Delhi style. The earliest examples of Indo-Islamic architecture, such as the Qutb Minar complex, emerged during this period, highlighting the influence of the Delhi Sultanates.

Mughal Architectural Marvels:

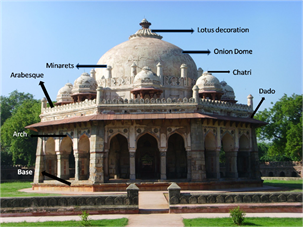

- Mughal architecture, a blend of Islamic, Persian, Turkish, and Indian styles, evolved from the 16th to the 18th centuries across the Mughal Empire. Characterized by large bulbous domes, slender minarets, massive halls, and delicate ornamentation, Mughal structures conveyed grandiosity and a sense of superiority. Noteworthy examples include the Qutb Minar, Tughlaqabad Fort, and Hauz Khas Complex.

Exquisite Mughal Inlay Art:

- Mughal architecture showcased remarkable inlay art, with Agra’s monuments illustrating its progressive development during the reigns of Akbar, Jahangir, and Shah Jahan. Marble inlay, known as ‘Pachchikari’ or ‘Parchinkari,’ emerged as a beautiful and popular form of Mughal art, featuring designs in precious or semi-precious stonework.

Mughal Gardens’ Tranquil Beauty:

- Mughal gardens, influenced by Persian garden design, were constructed in the char bagh structure, inspired by the quadrilateral garden layout mentioned in the Qur’an. These gardens aimed to depict an earthly utopia where humans coexisted harmoniously with nature. The layout included walkways, flowing water, pools, fountains, and canals, creating a serene and picturesque environment.

Enduring Impact on Subsequent Styles:

- Mughal architecture has significantly influenced later Indian architectural styles, including the Indo-Saracenic style of the British Raj, Rajput style, and Sikh style.

| Babur:

Babur, despite his lack of enthusiasm for Indian architecture, was extensively engaged in military campaigns during his five-year reign. Despite his military focus, he displayed a noteworthy interest in construction, with a few surviving structures attesting to his legacy. Notably, Babur’s enduring contributions include the construction of two mosques, one in Panipat and the other in Sambhal. Akbar: The Agra Fort, recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in Agra, Uttar Pradesh, stands as a testament to Akbar’s architectural prowess. Erected between 1565 and 1574, the fort’s architecture seamlessly blends Rajput planning with Mughal construction techniques. The Buland Darwaza, the world’s highest gateway, is a striking example of Mughal architecture within the fort, reflecting sophistication and technological advancements during Akbar’s reign. Jahangir: In the era of Mughal Emperor Jahangir, the Begum Shahi Mosque emerged as an architectural marvel. Built between 1611 and 1614 in the Walled City of Lahore, Pakistan, this mosque stands as a testament to the artistic and cultural richness of the early 17th century. Shah Jahan: Mughal architecture attained its zenith under Shah Jahan, who left an indelible mark with iconic constructions. Among his notable contributions are the Jama Masjid, Moti Masjid at Agra Fort, Shalimar Gardens in Lahore, the Wazir Khan Mosque, and the renowned Taj Mahal. The Taj Mahal, designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site, was erected between 1630 and 1649 in memory of Shah Jahan’s beloved wife Mumtaz Mahal. Characterized by white marble, intricate detailing, and a symmetrical layout, it stands as a timeless symbol of love and architectural brilliance. Aurangzeb: Commissioned by the sixth Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb, the Badshahi Mosque in Lahore, Pakistan, stands as a testament to his architectural patronage. Constructed between 1671 and 1673, it held the title of the world’s largest mosque at the time of its completion. Another noteworthy creation is the Bibi Ka Maqbara, located in Aurangabad, Maharashtra, India. Commissioned in 1660, this tomb dedicated to his first wife Dilras Banu Begum is a symbol of Aurangzeb’s conjugal fidelity and showcases the enduring beauty of Mughal architecture. |

Modern Architectural Synthesis in India:

The arrival of European influences in India heralded a transformative period in architectural evolution, where indigenous Indian traditions seamlessly merged with European styles, giving rise to the unique Indo-Saracenic architecture. This journey through the colonial period witnessed the creation of distinctive structures that define India’s rich architectural heritage.

- Colonial Architectural Footprint: The colonial imprint is most evident in institutional, civic, and utilitarian structures that shaped the urban landscape. Post offices, railway stations, rest houses, and government buildings emerged as prominent symbols of colonial architectural prowess.

- Portuguese Architectural Legacy: Portuguese influence, concentrated in Western India, left an enduring mark on churches, cathedrals, and schools. Exemplifying this fusion are iconic structures like the Basilica do Bom Jesus in Old Goa and the Cathedral de Santa Catarina, seamlessly blending Iberian and Renaissance architectural elements.

- French Aesthetics: French architectural aesthetics, prominently displayed in Puducherry, Bengal, Karaikal, and Mahe, embraced local materials. Noteworthy features include French shutter windows, intricately carved archways, and narrow street facades, reflecting a harmonious integration with the local environment.

- British Architectural Phases: The 18th-century introduction of the Palladian style, as witnessed in structures like Constantia in Lucknow, marked a pivotal phase. The 19th century witnessed a movement towards amalgamating Indian and Western architectural elements, leading to creations such as the museum in Jaipur and the Moor Market in Chennai. Iconic landmarks like the Gateway of India in Mumbai, designed by G. Wittet, exemplify seamless integration of Mughal architectural motifs.

The Victoria Terminus station in Mumbai stands as a masterpiece of Victorian Gothic revival architecture, a testament to the dynamic architectural expressions during this era.

- Indo-Saracenic Architecture: Emerging towards the end of the Victorian era, Indo-Saracenic architecture became a symbolic amalgamation of indigenous, Indo-Islamic, Gothic revival, and Neo-classical styles. Its distinctive features, including bulbous domes, overhanging eaves (Chhajja), vaulted roofs, chhatris, minarets, pavilions, and cusped arches, characterize iconic structures such as the Rashtrapati Bhavan, Egmore Railway Station, St. Matthias’ Church in Chennai, and the Chhatrapathi Shivaji Terminus.

This period of architectural evolution represents a dynamic fusion of diverse styles, symbolizing the cultural confluence facilitated by colonial interactions. It stands as a testament to the rich architectural heritage that defines India’s multifaceted journey through the ages.

| Architectural Legacy Forged by Sir Edwin Lutyens and Sir Herbert Baker:

In response to the burgeoning anti-imperialist sentiment in India, the British government marked a pivotal moment in the nation’s architectural trajectory by designating Delhi as its new capital in 1911. This historic juncture entrusted the monumental task of shaping New Delhi and its pivotal structures to the esteemed British architects, Sir Edwin Lutyens and Sir Herbert Baker. These visionary architects embarked on creating a grand urban street complex, a departure from the prevailing architectural norms in Indian cities. Their design philosophy seamlessly intertwined classical European and Indian elements, giving birth to a distinctive architectural style that would profoundly influence the city’s identity. Distinctive Architectural Features: The architectural masterpieces envisioned by Lutyens and Baker showcased a fusion of elements, including opulent colonnades, open verandas, tall and slender windows, chhajjas (wide roof overhangs), cornices, jaalis (circular stone apertures), and chhatris (free-standing pavilions). This amalgamation drew inspiration from both classical European architecture and the rich historical tapestry of Indian architectural heritage, resulting in a visually striking and unique aesthetic. Rashtrapati Bhavan: One of Sir Edwin Lutyens’s most iconic creations is the Rashtrapati Bhavan, formerly the Viceroy’s residence. Crafted from sandstone, this imposing structure seamlessly integrates design features such as canopies and jaali, drawing inspiration from the architectural splendor of Rajasthan. India Gate and Lutyens Delhi: Lutyens’s prolific contributions extend beyond Rashtrapati Bhavan, encompassing the design of India Gate and numerous other monuments in Delhi. In recognition of his enduring impact, New Delhi is often referred to as Lutyens Delhi, underscoring the city’s unique architectural legacy. Sir Herbert Baker’s Enduring Impact: Collaborating seamlessly with Lutyens, Sir Herbert Baker made substantial contributions to New Delhi’s architectural landscape. Noteworthy structures include the Central Secretariat building, Parliament House, and the residences of Members of Parliament. The architectural collaboration between Lutyens and Baker not only shaped the physical layout of New Delhi but also left an indelible imprint on the cultural and historical narrative of the city. Their ingenious fusion of diverse architectural elements stands as a testament to their visionary brilliance, creating a lasting legacy that continues to define the architectural identity of New Delhi. |

UPSC PREVIOUS YEAR QUESTIONS

1. With reference to ancient India, consider the following statements: (2023)

1. The concept of Stupa is Buddhist in origin.

2. Stupa was generally a repository of relics.

3. Stupa was a votive and commemorative structure in Buddhist tradition.

How many of the statements given above are correct?

(a) Only one

(b) Only two

(c) All three

(d) None

2. Consider the following pairs: (2023)

| Site | Well known for | |

| 1. | Besnagar | Shaivite cave shrine |

| 2. | Bhaja | Buddhist cave shrine |

| 3. | Sittanawasal | Jain cave shrine |

How many of the above pairs are correctly matched?

(a) Only one

(b) Only two

(c) All three

(d) None

3. Consider the following pairs: (2022)

| Site of Ashoka’s major rock edicts | Location in the State of |

| 1. Dhauli | Odisha |

| 2. Erragudi | Andhra Pradesh |

| 3. Jaugada | Madhya Pradesh |

| 4. Kalsi | Karnataka |

How many pairs given above are correctly matched?

(a) Only one pair

(b) Only two pairs

(c) Only three pairs

(d) All four pairs

4. The Prime Minister recently inaugurated the new Circuit House near Somnath Temple at Veraval. Which of the following statements are correct regarding Somnath Temple? (2022)

1. Somnath Temple is one of the Jyotirlinga shrines.

2. A description of Somnath Temple was given by Al-Biruni.

3. Pran Pratishtha of Somnath Temple (installation of the present day temple) was done by President S. Radhakrishnan.

Select the correct answer using the code given below:

(a) 1 and 2 only

(b) 2 and 3 only

(c) 1 and 3 only

(d) 1, 2 and 3

5. Which one of the following statements is correct? (2021)

(a) Ajanta Caves lie in the gorge of the Waghora river.

(b) Sanchi Stupa lies in the gorge of the Chambal river.

(c) Pandu-Lena Cave Shrines lie in the gorge of the Narmada river.

(d) Amaravati Stupa lies in the gorge of the Godavari river.

6. With reference to the cultural history of India, consider the following statements: (2018)

1. White marble was used in making Buland Darwaza and Khankah at Fatehpur Sikri.

2. Red sandstone and marble were used in making Bara Imambara and Rumi Darwaza at Lucknow.

Which of the statements given above is/are correct?

(a) 1 only

(b) 2 only

(c) Both 1 and 2

(d) Neither 1 nor 2

7. What is/are common to the two historical places known as Ajanta and Mahabalipuram? (2016)

1. Both were built in the same period.

2. Both belong to the same religious denomination.

3. Both have rock-cut monuments.

Select the correct answer using the code given below.

(a) 1 and 2 only

(b) 3 only

(c) 1 and 3 only

(d) None of the statements given above is correct

8. Discuss the significance of the lion and bull figures in Indian mythology, art and architecture. (2022)

9. The rock-cut architecture represents one of the most important sources of our knowledge of early Indian art and history. Discuss. (2020)