Cross the boulders in the Indus Waters Treaty.

Relevance:

GS Paper – 2, India and its Neighborhood, Groupings & Agreements Involving India and/or Affecting India’s Interests

About Indus Water Treaty

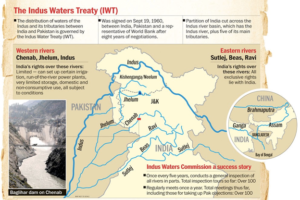

- The Indus Waters Treaty (IWT), brokered by the World Bank, which has again become a source of contention between India and Pakistan, considerably encapsulates the principle of equitable allocation rather than the principle of appreciable harm.

- Both India and Pakistan are granted exclusive rights to utilize the waters of the rivers allocated to them without harming others’ interests.

- Under the IWT, India has unrestricted use of the three eastern rivers (Ravi, Beas, and Sutlej), while Pakistan enjoys similar rights over the three western rivers (Indus, Jhelum, and Chenab). India is allowed to store 3.60 million-acre feet (MAF) (0.40 MAF on the Indus, 1.50 MAF on the Jhelum and 1.70 MAF on the Chenab) of water.

- The sector-wise allocation is 2.85 MAF for conservation storage (divided into 1.25 MAF for “general storage” and 1.60 for “power storage”) and an additional 0.75 MAF for “flood storage”.

About Indus River

- Indus River System is a Himalayan river system and is one of the largest river basins in the world.

- The Indus River, also known as Sindhu river, is a part of one of the most fertile regions of the Indian sub-continent and the world.

- The main tributaries of the Indus River form the Indus River System, which includes Indus, Jhelum, Chenab, Ravi, Beas, and Satluj.

History of the Indus Waters Treaty

- The Indus river basin has six rivers – Indus, Jhelum, Chenab, Ravi, Beas and Sutlej, originating from Tibet and flowing through the Himalayan ranges to enter Pakistan, ending in the south of Karachi.

- In 1947, the line of partition, aside from delineating geographical boundaries for India and Pakistan, also cut the Indus river system into two.

- Initially, the Inter-dominion accord of May, 1948 was adopted, where both countries, after meeting for a conference, decided that India would supply water to Pakistan in exchange for an annual payment made by the latter.

- This agreement however, soon disintegrated as both the countries could not agree upon its common interpretations.

- In 1951, in the backdrop of the water-sharing dispute, both the countries applied to the World Bank for funding of their respective irrigation projects on Indus and its tributaries, which is when the World Bank offered to mediate the conflict.

- Finally in 1960, the World Bank mediated agreement was reached between the two countries and the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) was signed by former Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and then President of Pakistan, Ayyub Khan.

Key provisions of the Indus Waters Treaty

Water Sharing Provisions

- The treaty prescribed how water from the six rivers of the Indus River System would be shared between India and Pakistan.

- The three western rivers—Indus, Chenab and Jhelum—were allotted to Pakistan for unrestricted use.

- The three Eastern rivers—Ravi, Beas and Sutlej—were allocated to India for unrestricted usage.

- Thus by provisions of treaty 80% of the share of water or about 135 Million Acre Feet (MAF) went to Pakistan while India left with the rest 33 MAF or 20% of water for its usage.

Administrative provisions

- It required both the countries to establish a Permanent Indus Commission constituted by permanent commissioners on both sides.

- The commission will serve as a forum for exchange of information on the rivers, for continued cooperation and as the first stop for the resolution of conflicts.

Dispute resolution mechanism

- First, “Questions” on both sides can be resolved at the Permanent Commission, or can also be taken up at the inter-government level.

- Disputes/differences unresolved on the first level can be taken to the World Bank who appoints a Neutral Expert (NE) to come to a decision.

- Eventually, if either party is not satisfied with the NE’s decision or in case of “disputes” in the interpretation and extent of the treaty, matters can be referred to a Court of Arbitration.

Annulment provisions

- The treaty does not provide a unilateral exit provision to either country. It is supposed to remain in force unless both the countries ratify another mutually agreed pact.

Criticisms

- Internationally, the Treaty is seen as one of the most successful cases of conflict resolution but between the two countries, it has seeded dissatisfaction and conflicts regarding its interpretation and implementation.

- The treaty is highly technical leading to far-ranging divergences between the two countries in terms of interpretations. For example, the treaty says that storage systems can be built but to a limited extent.

- However, the technical details make it difficult to conclude under what circumstances projects can be carried out. Another concern is the tense political relations between the two countries.

What is the History of the Dispute over the Hydel Projects?

- In 2015, Pakistan asked that a Neutral Expert should be appointed to examine its technical objections to the Kishanganga and Ratle HEPs. But the following year, Pakistan unilaterally retracted this request, and proposed that a Court of Arbitration should adjudicate on its objections.

- In August 2016, Pakistan had approached the World Bank seeking the constitution of a Court of Arbitration under the relevant dispute redressal provisions of the Treaty.

- Instead of responding to Pakistan’s request for a Court of Arbitration, India moved a separate application asking for the appointment of a Neutral Expert.

- India had argued that Pakistan’s request for a Court of Arbitration violated the graded mechanism of dispute resolution in the Treaty.

- In March 2022, the World Bank decided to resume the process of appointing a Neutral Expert and a Chairman for the Court of Arbitration.

From the Indian point of view

- The basic dissatisfaction is that the treaty prevents it from building any storage systems on the western rivers, even though it allows building storage systems under certain exceptional circumstances.

From Pakistan’s point of view

- Due to its suspicions, stays aware of every technical aspect of the project and deliberately tries to get it suspended.

- The matter is further aggravated by the fact that the western rivers lie in the disputed region of Jammu and Kashmir, a subject of a tussle between both since independence.

Recent developments

- Indian government in January 2023 notified Pakistan of its intent to modify the IWT. It says this extreme step is due to Pakistan’s intransigence over objections to two Indian hydropower projects in Jammu and Kashmir.

- The 330MW Kishanganga hydroelectric project (Jhelum) and the 850MW Ratle hydroelectric project (Chenab). India has argued since 2006, when the objections began, that the projects were within the treaty’s fair water use.

- However, Pakistan has refused to conclude negotiations with India in the bilateral mechanism — the Permanent Indus Commission (PIC) of experts that meets regularly — and has often sought to escalate it.

- As a result, the World Bank appointed a neutral expert, but Pakistan pushed for the case to be heard at The Hague.

- India has objected to this sequencing, as it believes that each step should be fully exhausted before moving on to the next.

- While India was able to prevail over the World Bank to pause the process in 2016, Pakistan persisted, and since March 2022, the World Bank has agreed to have both a neutral expert and a Court of Arbitration (CoA) hear the arguments.

- India attended the hearings with the neutral expert last year, but has decided to boycott the CoA at The Hague that began its hearing recently.

Way Forward

- In the last six decades the Indus Waters Treaty has been one of the most successful water-sharing endeavors in the world today. However, there is a need to update certain technical specifications and expand the scope of the agreement to address climate change.

- Therefore there is a need to renegotiate the treaty terms, update certain technical specifications and expand the scope of the agreement to address demands of the two countries amid the rising climate crisis.

Source: The Hindu