COURT ON CLIMATE RIGHT

Syllabus:

GS 2:

- Government Policies and Interventions for Development in various sectors

GS 3:

- Conservation, Environmental Pollution and Degradation, Environmental Impact Assessment.

Why in the News?

The recent Supreme Court judgment in M.K. Ranjitsinh and Ors. vs Union of India & Ors. has brought attention to climate change jurisprudence by recognizing a constitutional right to be free from the adverse effects of climate change, sparking discussions on the need for comprehensive climate legislation in India.

Source: Minneapolis

The Supreme Court Judgment

- Recent ruling: The Supreme Court of India, in M.K. Ranjitsinh and Ors. vs Union of India & Ors., has significantly impacted India’s climate change jurisprudence.

- Constitutional right: The Court identified the right to be free from the adverse effects of climate change as part of the Constitution.

- Core sources: This new climate right is rooted in the constitutionally guaranteed right to life (Article 21) and right to equality (Article 14).

- Government agenda: The judgment presents an opportunity for the new government to create systematic governance around climate change.

- Intriguing opportunity: This decision encourages thinking about enacting comprehensive climate legislation.

A New Right Around Climate

- Ongoing unpacking: Scholars and legal practitioners are still interpreting the implications of the judgment.

- Case specifics: The case involved building electricity transmission lines through the habitat of the critically endangered Great Indian Bustard.

- Government claim: The government argued that protecting the bird’s habitat affected renewable energy potential.

- Court’s modification: The Court modified the order to prioritize transmission infrastructure for renewable energy development.

- Seismic aspect: The recognition of a constitutional climate right opens the door to climate litigation, empowering citizens to demand government action.

About the Human Right to a Healthy Environment

|

Legislative Approach vs. Judicial Decisions

- Judicial patchwork: Court-based actions may lead to an incomplete and judiciary-led patchwork of protections.

- Policy contingency: Realizing climate rights through judicial orders depends on subsequent policy actions.

- Preferred legislation: Climate legislation might be a better approach to protect climate rights comprehensively.

- Framework legislation: The judgment acknowledges the absence of an ‘umbrella legislation’ for climate change in India.

- Global examples: Framework legislation can set the vision for engaging with climate change, create necessary institutions, and establish structured governance processes.

Tailoring Legislation to India

- Unique context: Indian climate legislation should be tailored to the local context, not copied from other countries.

- Low-carbon future: India needs to transition to a low-carbon energy future, as highlighted in the Ranjitsinh judgment.

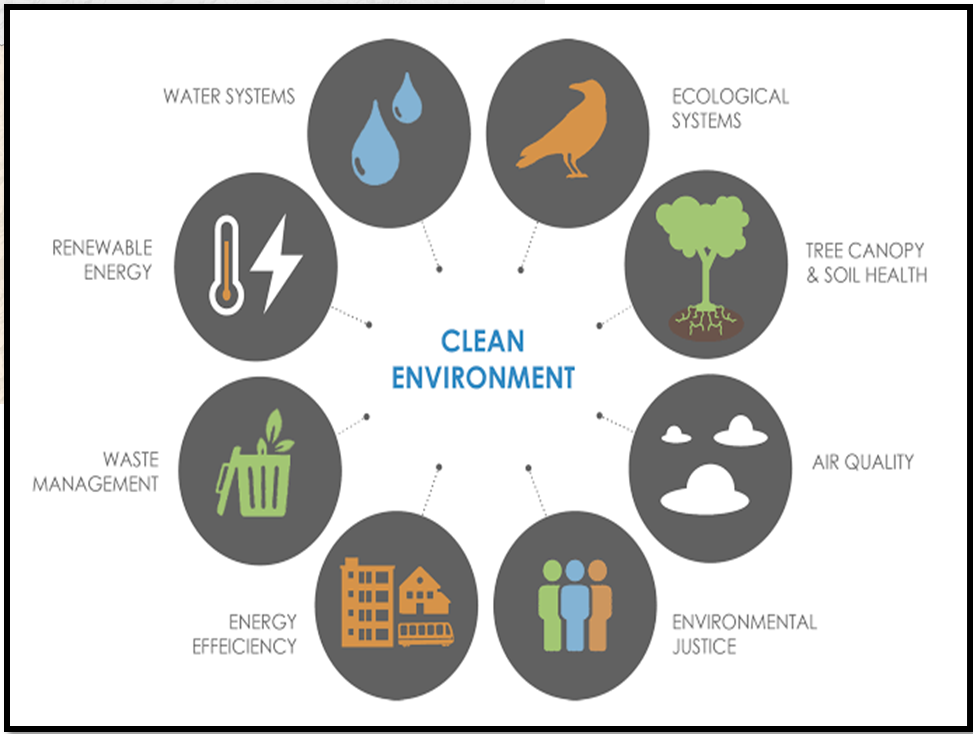

- Supportive regulation: Climate legislation should create a regulatory environment for sustainable cities, buildings, and transport networks.

- Local adaptation: The law should enable adaptation measures, such as heat action plans and climate-resilient crops.

- Social equity: Legislation should consider social equity in achieving climate resilience and mitigation.

Comprehensive Climate Law

- Omnibus challenges: A single, comprehensive law for all climate issues is not feasible due to existing legal frameworks.

- International lessons: Learn from other countries’ climate laws, avoiding narrow regulatory focus and emphasizing enabling development.

- Procedural orientation: An enabling law would create institutions, processes, and standards for mainstreaming climate change across sectors.

- Knowledge sharing: The law should support transparency, public participation, and expert consultation.

- Setting targets: It should include procedures for setting and revising targets, timelines, and reporting mechanisms.

The Factor of Federalism

- Effective federalism: Ensure the climate law works within India’s federal structure, empowering States and local governments.

- Sub-national roles: Many climate-relevant areas, such as urban policy and agriculture, fall under state or local authority.

- Coherent action: The law should set a national framework while decentralizing power to enable effective local action.

- Beyond government: The enabling role should extend to businesses, civil society, and communities, involving them in decision-making.

- Diverse participation: An effective climate law should provide opportunities for diverse segments of society to contribute their knowledge and solutions.

Challenges

- Judicial Patchwork: Relying on court-based actions can result in an incomplete and inconsistent patchwork of protections, making it difficult to create a cohesive climate policy.

- Policy Dependency: Judicial decisions alone are not sufficient; they require subsequent policy actions to be effective, leading to potential delays and inefficiencies.

- Lack of Comprehensive Law: India currently lacks an overarching, framework legislation to address climate change, hindering coordinated and systematic governance.

- Copying Foreign Models: Adopting climate laws from other countries without tailoring them to India’s unique context may lead to ineffective solutions that do not address local needs.

- Sector-Specific Gaps: Existing legal frameworks do not comprehensively cover all areas necessary for climate resilience, such as sustainable urban planning, transport, and agriculture.

- Federalism Complexity: Ensuring effective implementation of climate laws within India’s federal structure is challenging due to the division of authority between national, state, and local governments.

- Inclusivity and Participation: Engaging diverse stakeholders, including businesses, civil society, and communities, in the decision-making process is complex but essential for holistic solutions.

- Balancing Equity: Crafting climate legislation that adequately addresses social equity and ensures fair distribution of resources and opportunities is a significant challenge.

Way Forward

- Comprehensive Legislation: Develop a comprehensive climate law that sets a clear vision, creates necessary institutions, and establishes structured governance processes across sectors.

- Tailored Solutions: Ensure that climate legislation is specifically tailored to India’s context, addressing local environmental challenges, social equity, and economic conditions.

- Institutional Framework: Create a robust institutional framework to support knowledge-sharing, transparency, public participation, and expert consultation.

- Adaptive Mechanisms: Incorporate mechanisms for regular review and adaptation of policies to respond to evolving climate challenges and scientific advancements.

- Decentralized Empowerment: Empower state and local governments with the authority, information, and financial resources needed to implement effective climate actions within their jurisdictions.

- Inclusive Participation: Facilitate meaningful participation of all stakeholders, including marginalized communities, in climate decision-making processes to ensure diverse perspectives and knowledge are integrated.

- Integrated Approach: Develop an integrated approach that combines mitigation and adaptation strategies, ensuring that climate resilience is built into all sectors, including agriculture, water, and infrastructure.

- Equity Focus: Prioritize social equity in climate legislation, ensuring that vulnerable populations are protected and have access to resources and opportunities for sustainable development.

Conclusion:

The Supreme Court’s landmark judgment underscores the urgency for comprehensive climate legislation in India. Tailoring such laws to local contexts, empowering states, and ensuring inclusivity and equity are crucial steps forward to address the multifaceted challenges posed by climate change effectively.

Source: The Hindu

Mains Practice Question:

Discuss the significance of the Supreme Court’s recognition of a constitutional right to be free from the adverse effects of climate change. How can India develop a comprehensive legislative framework to address climate change while ensuring social equity and federal cooperation?