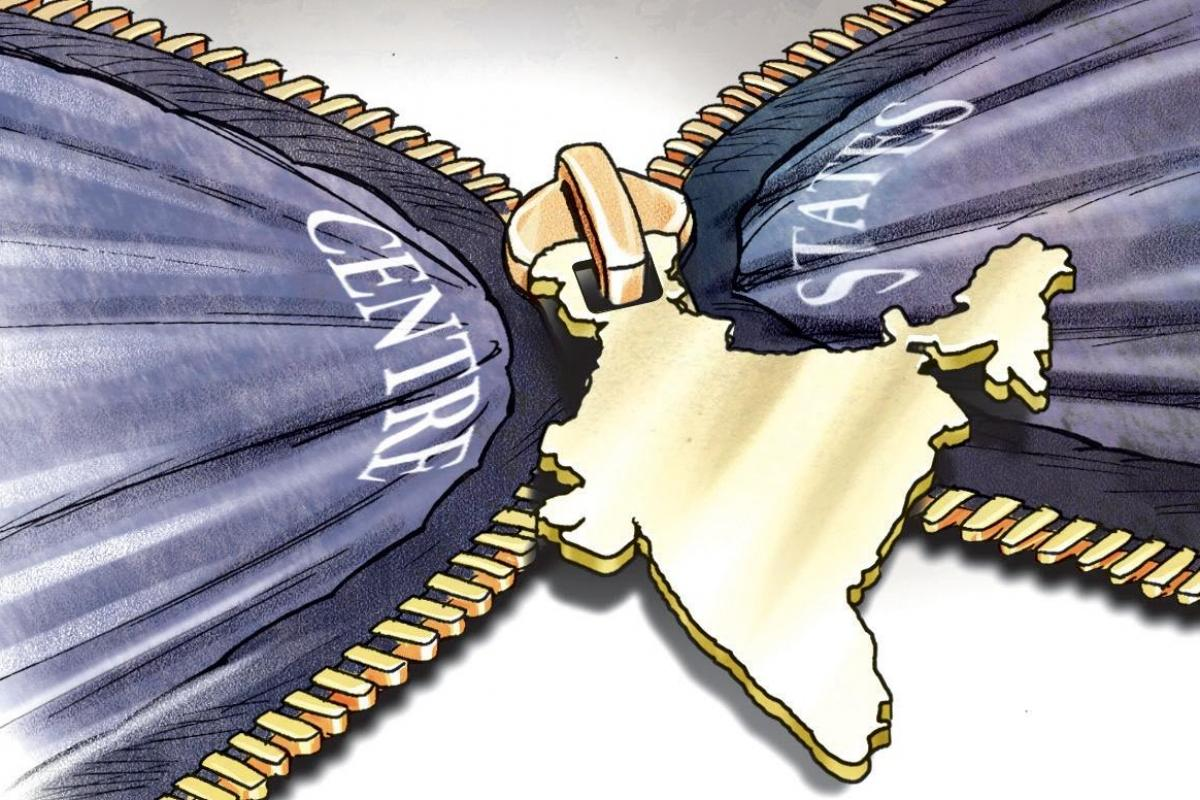

CENTRE-STATE RELATIONS

Introduction

- The Centre-State relationship in India pertains to the distribution of powers and responsibilities between the federal government (the Centre) and individual states. This delicate balance is a fundamental aspect of India’s federal system, as enshrined in the Constitution, and is crucial for effective governance and cooperation between the two tiers of government.

- The Constitution of India provides explicit provisions to guide Centre-State relations. These provisions are categorized into three key areas:

- Legislative Relations (Articles 245 to 255): These provisions outline the distribution of legislative authority between the Centre and the States. Legislative powers are divided into three lists: the Union List (with 100 subjects), the State List (with 61 subjects), and the Concurrent List (with 52 subjects). This division demarcates the areas in which each level of government can make laws, ensuring clarity and cooperation.

- Administrative Relations (Articles 256 to 263): The Constitution defines administrative jurisdiction for the Union and State Governments concerning subjects in the Union List and State List, respectively. This delineation clarifies the roles and responsibilities of each level of government in executing administrative functions within their designated domains.

- Financial Relations (Article 268 to 293): Provisions governing financial relations are detailed in these articles. A significant aspect of these provisions is the establishment of a Finance Commission every five years. This commission is tasked with making recommendations on the distribution of financial resources between the Centre and the States. These recommendations play a vital role in ensuring financial stability and equity in the federal structure.

- These constitutional provisions form the backbone of Centre-State relations in India, promoting cooperative federalism and balancing powers and responsibilities between the different tiers of government.

Legislative Relations

- The legislative relations between the Centre and the states are comprehensively addressed in Articles 245 to 255 of Part XI of the Indian Constitution. These articles establish the foundation for dividing legislative powers based on territory and subjects. Additionally, the Constitution accommodates parliamentary legislation in state matters during specific exceptional circumstances and provides for the Centre’s control over state legislation in certain cases. In summary, Centre-state legislative relations encompass four key aspects:

- Territorial Extent: Determining the territorial reach of Central and state legislation.

- Distribution of Legislative Subjects: Allocating legislative authority over various subjects.

- Parliamentary Legislation in State Field: Allowing for parliamentary laws in state matters under specific extraordinary situations.

- Centre’s Control Over State Legislation: Outlining circumstances where the Centre can influence or intervene in state legislation.

Territorial Extent

- Parliament’s Legislative Powers: Parliament has the authority to enact laws that apply to the entire territory of India, which includes the union territories, states, and union territories.

- State Legislative Powers: State legislatures can enact laws that apply to the entire state or specific portions of it. State laws generally do not have extraterritorial applicability unless there is a sufficient connection between the state and the subject matter of the law.

- Extraterritorial Legislation: Only Parliament has the authority to enact “extraterritorial” legislation, which means laws that can have an impact outside of a specific state’s jurisdiction.

- President’s Authority for Union Territories: For union territories like the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Daman and Diu, Dadra and Nagar Haveli, and Lakshadweep, the President can issue regulations that have the same legal effect as laws passed by Parliament. These regulations are used to govern these territories.

- Governor’s Authority in States: Governors have the authority to order that an act of Parliament does not apply to a designated territory within a state, or they can specify modifications and exceptions when applying such laws. This allows for some degree of flexibility in applying central laws at the state level.

- Special Provisions for Northeastern States: In Assam, Meghalaya, Tripura, and Mizoram, the President has similar authority to the Governor in other states. They can direct an act of Parliament not to apply or to apply with specific modifications.

Distribution of Legislative Subjects

- Union List: The Union List contains subjects on which only the Parliament of India has the authority to enact laws. States cannot legislate on matters listed in the Union List.

- State List: The State List includes subjects on which the state legislatures have exclusive authority to enact laws. Parliament cannot legislate on matters listed in the State List.

- Concurrent List: The Concurrent List comprises subjects on which both the state legislatures and the central government (Parliament) can pass legislation. If there’s a conflict between a central law and a state law on a concurrent list item, the central law takes precedence.

- Residuary Powers: Parliament has the authority to enact legislation on matters not specifically listed in any of the three lists. These are referred to as residuary powers.

- Hierarchy of Laws: In the case of a conflict between laws related to the same subject matter in different lists, there is a hierarchy:

- Union List takes priority over State List.

- Concurrent List takes priority over State List.

- Resolution of Disputes: In the event of a disagreement between a central law and a state law on a concurrent list item:

- The central law takes precedence, unless the state law has been reserved for the President’s consideration and has received his consent, in which case the state law takes precedence in that state.

- However, Parliament can override state laws by passing a law on the same subject.

Parliamentary Legislation in The State Field

- Rajya Sabha Resolution: If the Rajya Sabha (the upper house of Parliament) passes a resolution with the support of two-thirds of the members present and voting, allowing Parliament to legislate on a State List subject in the best interests of the country, Parliament can do so for a maximum period of one year. This resolution can be renewed, but not for more than one year at a time. After six months, the laws enacted under this resolution are no longer in effect. In case of a conflict between state and union laws on the same subject, the union law takes precedence.

- National Emergency: During a national emergency, Parliament has the authority to legislate on State List subjects. The laws enacted under this authority cease to be effective six months after the national emergency ends. However, state legislatures can pass laws on the same subject, but if there is a conflict between state and union laws, the union law prevails.

- State Request: If a state requests Parliament, passing a resolution to that effect, Parliament is granted the authority to legislate on the subjects specified in the resolution. Once this resolution is passed, the state relinquishes its legislative rights in that area.

- International Agreements: Parliament can enact laws on State List subjects to enforce international agreements.

- President’s Rule: During the period of President’s Rule, which is imposed when there is a breakdown of constitutional machinery in a state, Parliament can pass laws on state matters. The laws enacted during this period remain in effect even after the President’s Rule ends. Subsequently, the state legislature can pass legislation to modify or repeal the enacted laws as it sees fit.

Centre’s Control Over State Legislation

- Governor’s Power to Reserve Bills: The Governor of a state has the authority to reserve certain types of bills passed by the state legislature for the President’s consideration. This means that before such bills become law in the state, they must be approved by the President. The President has complete control over these reserved bills, and their enactment is subject to the President’s discretion.

- Prior Approval for Specific Topics in State List: Some subjects listed in the State List of the Constitution are of national importance. For bills related to these specific topics, such as inter-state trade and commerce, the state legislature can only introduce and pass such bills with the prior approval of the President. This means that the state government must seek and obtain the President’s consent before legislating on these subjects.

- Financial Emergency: In the event of a financial emergency in a state, the President may direct the state to set aside money bills and other financial bills for his consideration. During a financial emergency, the President’s approval is necessary for the state’s financial matters, including taxation and spending.

- These provisions serve as safeguards and mechanisms for the central government to oversee and control certain aspects of state legislation, especially in cases where the interests of the entire nation or the state’s financial stability are at stake. They are designed to ensure that state laws do not conflict with the broader national interests and that the President, as the head of state, has a role in these critical matters.

Administrative Relations

Allocation of Executive Powers:

- The executive power is shared between the central government and the states based on the subjects listed in the Union List, State List, and Concurrent List.

- The center’s executive power extends over subjects in the Union List and matters arising from treaties or agreements.

- The state’s executive jurisdiction covers topics listed in the State List.

- The executive power in matters listed in the Concurrent List is vested in the states.

- States have obligations to ensure the enforcement of central laws and not obstruct the exercise of their executive powers. Failure to comply can result in the application of Article 365, which may lead to the use of Article 356 (President’s Rule) in the state.

Guidance and Delegation of Functions:

- The central government can provide guidance to states in certain matters such as communication systems, railway safety, linguistic minority education, and welfare plans for Scheduled Tribes.

- Mutual delegation of executive functions is allowed. The President may assign union executive duties to state governments with the state’s consent, and governors can assign state executive functions to the central government with federal government approval. Such delegations may be conditional or unconditional.

- The constitution allows states to delegate executive powers to the union, but Parliament, not the President, makes such delegations.

Cooperation Mechanisms:

- Disputes regarding the use, distribution, and control of interstate rivers and river valleys can be adjudicated by Parliament.

- The President can establish an Inter-state Council to research and discuss matters of mutual interest between the center and the states.

- Public acts, records, and judicial processes of the center and each state are recognized and enforceable throughout India.

- Parliament can appoint appropriate authorities to carry out constitutional provisions related to interstate trade, commerce, and intercourse.

All India Services

- In India, the Indian Administrative Service (IAS), Indian Police Service (IPS), and Indian Forest Service (IFS) collectively form the All India Services. These services succeeded the colonial Indian Civil Service (ICS) and Indian Police (IP) in 1947. Article 312 of the Indian Constitution grants Parliament the authority to establish All India Services upon a resolution passed by the Rajya Sabha. The IAS, IPS, and IFS are unified services with consistent rights, status, and pay scales nationwide.

- The significance of these All India Services lies in their role in upholding high-quality administration at both the central and state levels, ensuring uniformity in the administrative system across the country, and promoting cooperation and coordination between the central and state governments on matters of mutual interest. These services are known for their selectivity, rigorous training, and their crucial role in shaping and implementing government policies and programs, contributing to the effective functioning of the Indian bureaucracy.

Public Service Commission

- Governor’s Appointment and Removal: The Governor of a state appoints the chairman and members of the State Public Service Commission. However, they can only be removed from their positions by the President.

- Combined Public Service Commission: If two or more states request it, Parliament can establish a combined Public Service Commission. In such cases, the President selects the chairman and members of the State Public Service Commissions that are part of the combined commission.

- Assistance from UPSC: Upon the request of the Governor, and with the President’s consent, the Union Public Service Commission (UPSC) can provide assistance to the State Public Service Commission in matters related to recruitment and other relevant areas.

- Joint Recruitment Strategies: The UPSC can collaborate with states to develop and implement joint recruitment strategies for services that require candidates with specific qualifications. This cooperation aims to streamline the recruitment process and ensure efficiency in filling positions.

Integrated Judicial System

- Integrated Judicial System: India has an integrated judicial system that is responsible for administering and enforcing both federal (central) and state laws. This system helps maintain uniformity in the application of laws across the country.

- Appointment of High Court Justices: The President of India, in consultation with the Chief Justice of India and the governor of the respective state, appoints the judges of a high court. These appointments are made to ensure the impartiality and independence of the judiciary. The President also has the authority to remove or transfer high court judges.

- Common High Courts: Parliament has the authority to establish common high courts for two or more states. This provision allows for the efficient administration of justice and judicial resources in regions that share a high court’s jurisdiction.

Relations During Emergency

- National Emergency: During a national emergency, the central government (the Union) can issue instructions to state governments on any subject, effectively taking control of state affairs to ensure the nation’s security and stability.

- State Emergency: The President has the authority to assume the functions of the state government, including the powers vested in the Governor or any other executive authority in the state, for the duration of the emergency.

- Financial Emergency: In the event of a financial emergency, the central government can direct states to follow financial propriety canons and take measures to restore financial stability. The President can issue essential directives during a financial emergency, which may include actions like reducing the wages of state employees and high court judges, aimed at addressing the financial crisis.

Financial Relations

Allocation of Taxing Powers

- Union List: Parliament has the exclusive authority to levy taxes on the subjects listed in the Union List. States cannot impose taxes on these subjects.

- State List: State legislatures have exclusive authority to levy taxes on the subjects listed in the State List. The central government cannot impose taxes on these subjects.

- Concurrent List: Both the central government and state governments have the authority to impose taxes on the subjects listed in the Concurrent List. This means that there can be overlapping taxation powers on these subjects, but any inconsistency is usually resolved through legislation and legal mechanisms.

- Residuary Power of Taxation: The Parliament holds the residuary power of taxation. This means that in the absence of specific provisions in the lists, Parliament has the authority to impose taxes on subjects not explicitly mentioned in the Union List, State List, or Concurrent List.

The restriction placed by the constitution on taxation power of the state

- Taxation of Professions, Trades, Callings, and Occupations: State legislatures have the authority to impose taxes on professions, trades, callings, and occupations. However, there is a restriction that no single individual’s total annual payment should exceed Rs 2,500.

- Sales Tax: States can levy taxes on the sale or purchase of goods, excluding newspapers. However, this power is subject to several conditions:

- No tax can be imposed on sales or purchases made outside of the state.

- No tax can be levied on sales or purchases made during the import or export process.

- No tax can be imposed on sales or purchases in the course of interstate trade and commerce.

- Taxes on the sale or purchase of commodities recognized by Parliament as being of special importance in interstate trade and commerce are subject to the limits and conditions set by Parliament.

- Electricity Tax: States cannot levy a tax on the sale of electricity if it is consumed by or sold to the central government or if it is consumed in the construction, maintenance, or operation of any railway by or sold to a railway company for the same purpose.

- Fee on Water or Power for Interstate River Authority: A state can levy a fee on water or power sold to an interstate river authority constituted by Parliament for the development of a river. Such imposition requires a statute that has acquired the President’s consent.

Distribution of Tax Revenues

- Centre Imposes, State Collects, and Retains Taxes (Article 268): Taxes imposed by the central government, such as stamp duty and certain excise duties, are collected and retained by the state governments. The proceeds from these taxes go into the state’s consolidated fund.

- Centre Levies and Collects, State Collects (Article 269): Taxes on the sale or purchase of goods in interstate commerce are levied and collected by the central government, but the responsibility for collection lies with the state governments. The proceeds from these taxes are deposited in the state’s consolidated fund.

- Centre Levies and Collects, Division of Taxes (Article 270): All taxes, excluding those mentioned above, surcharges, and cess, are imposed and collected by the central government. However, the proceeds are divided between the central government and the states. The distribution of these taxes is determined by the President based on recommendations from the Finance Commission.

- State-Imposed, Collected, and Retained Taxes: These are taxes solely under the jurisdiction of the state governments and are listed in the State List of the Constitution. Examples include taxes on agricultural income, excise duties on alcohol, taxes on professions, and property taxes.

- This tax distribution framework helps maintain a balance of fiscal powers between the central and state governments, allowing both levels of government to raise revenue independently and in accordance with their respective responsibilities.

Distribution of Non-tax Revenues

- Central Government’s Non-Tax Revenue Streams:

- Postal and telegraph services

- Railroads

- Banking

- Broadcasting

- Coinage and currency

- Central public sector enterprises

- Escheat and lapse (revenue from unclaimed property)

- State Governments’ Non-Tax Revenue Streams:

- Irrigation

- Forests

- Fisheries

- State public sector enterprises

- Escheat and lapse (revenue from unclaimed property)

- Grants-in-Aid to States:

- Statutory Grants: Article 275 of the Constitution authorizes the Parliament to provide grants to states in need of financial assistance. These grants are not uniformly provided to all states and may vary. The funds for these grants are charged to India’s Consolidated Fund and are distributed to states based on recommendations from the Finance Commission.

- Discretionary Grants: Under Article 282, both the central and state governments have the authority to issue grants for any public purpose, even if it falls outside their legislative jurisdiction. The central government is not obligated to provide these grants, and the decision is at its discretion.

- Other Grants: The Constitution allows for one-time grants for specific purposes. For example, grants were provided instead of export duties on jute and jute products for the states of Assam, Bihar, Odisha, and West Bengal. These grants were to be distributed for ten years from the beginning of the Constitution based on the Finance Commission’s recommendations.

| Trends in Centre-State Relations |

o The 44th Amendment Act repealed Article 357(A), which allowed the central government to deploy the military to address law and order issues in the states. In the 1980 midterm elections, the Congress party regained power and dismissed the Janata party governments in nine states. o This period also witnessed the emergence of regional parties demanding greater autonomy, with several states forming governments led by these regional parties. To address these autonomy demands, the southern states announced the formation of a regional council. o In response to these developments, the Sarkaria Commission was established to examine the center-state relationship. The Rajiv Gandhi government, for political reasons, sought alliances with regional parties, and attempted to centralize power by directly engaging with District Magistrates, bypassing state administrations. This centralization trend was evident in initiatives such as the Panchayati Raj Bill and the Jawahar Rojgar Yojana.

o With the Congress party’s defeat, this election marked the end of one-party rule at the center and the beginning of coalition administrations. Regional parties gained prominence in the federal cabinet and started asserting themselves more actively at the national level. o This shift toward greater federal principles can be classified into two main categories: Political Federalism and Economic Federalism. Political Federalism

|

Important Recommendations On Centre – State Relations

Administrative Reforms Commission

- Inter-State Council (Article 263): The Constitution of India mandates the formation of an Inter-State Council, which serves as a platform for cooperation and coordination among states and between the center and the states.

- Appointment of Governors: Governors are appointed with an emphasis on extensive public service experience and nonpartisan attitudes to ensure the impartial and effective functioning of states.

- Decentralization of Power: Efforts have been made to give states more power and autonomy in various policy areas to enhance their governance and decision-making abilities.

- Transfer of Financial Resources: There is a push to transfer more financial resources to states to reduce their reliance on the federal government. This includes the sharing of central taxes and the allocation of funds for state development.

- Deployment of Central Armed Forces: Central armed forces can be deployed in states at their request or on their initiative to address law and order situations and other security concerns.

- Committees and Commissions:

- The Rajamannar Committee, appointed by the Tamil Nadu government, offered recommendations to address the power imbalance between the center and the states.

- The Anandpur Sahib Resolution in Punjab and similar recommendations in West Bengal were proposed to address disparities in center-state relations.

- The Sarkaria Commission, established in 1983, and the Punchhi Commission, formed in 2007, were government-appointed bodies to assess and make recommendations regarding the dynamics of center-state relations in India.

Sarkaria Commission Recommendation

- Setting Up a Permanent Inter-State Council: The establishment of a permanent Inter-State Council could facilitate ongoing cooperation and coordination among states and between the central government and states.

- Limited Use of Article 356 (President’s Rule): Article 356, which allows for the imposition of President’s Rule in states, should only be employed when absolutely necessary to protect the autonomy of state governments.

- Strengthening the All-India Service: Enhancing the institution of All-India Services, such as the Indian Administrative Service (IAS) and Indian Police Service (IPS), can contribute to more effective governance across the country.

- Retaining Residuary Power with Parliament: The Parliament should continue to hold residuary powers, which means that it retains authority over subjects not explicitly allocated to the central or state governments.

- Transparency in Presidential Veto: When the President exercises veto power over state bills, the reasons for the veto should be disclosed to the states for greater transparency and accountability.

- Center’s Right to Deploy Armed Forces: While the central government should have the authority to deploy its armed forces in states without state approval, it is advisable that states are consulted in such matters to ensure cooperation and understanding.

- Consultation Procedure for Chief Minister Appointment: The procedure for consulting the Chief Minister when appointing the state government should be clearly outlined in the constitution to formalize the process.

- Governor Tenure: Governors should be allowed to complete their full five-year terms to ensure stability and continuity in state governance.

- Appointment of Commissioner for Linguistic Minorities: The position of Commissioner for Linguistic Minorities should be filled to address linguistic minority issues effectively.

Punchhi Commission

- Governor Tenure and Removal: Governors should have a fixed five-year tenure and can only be removed through the impeachment procedure, ensuring stability in state governance.

- Parliamentary Primacy in State Subjects: When dealing with subjects entrusted to the states, the central government should exercise caution and respect the primacy of the state legislatures.

- Governor Appointment Requirements:

- Governors should be well-known in certain fields.

- They should be non-residents of the state they are appointed to.

- They should be non-political figures not involved in local politics.

- They should not have been involved in recent political activities.

- Five-Year Term Limit for Governments: State governments should have a fixed five-year term limit to promote regular elections and political stability.

- Extension of Impeachment Procedure: The impeachment procedure applicable to the President could be extended to governors for their removal.

- Governor’s Role in Government Formation: Governors should play a role in ensuring that Chief Ministers demonstrate their majority on the floor of the House, setting a time restriction for this process.

- Bommai Case Rules: The principles established in the Bommai case, a landmark legal case regarding President’s rule in states, should be considered when dealing with such situations.

- Enhanced Use of the Inter-State Council: The Inter-State Council should be utilized more frequently to promote cooperation and coordination between the central government and states.

| Frictional Areas in Centre-state Relations |

These issues underscore the complex dynamics of center-state relations in India, reflecting the challenges and opportunities that come with a diverse and federal system of governance. Addressing these concerns requires careful consideration and adherence to constitutional principles. |

UPSC PREVIOUS YEAR QUESTIONS

1. Which one of the following suggested that the Governor should be an eminent person from outside the State and should be a detached figure without intense political links or should not have taken part in politics in the recent past? (2019)

1. First Administrative Reforms Commission (1966)

2. Rajamannar Committee (1969)

3. Sarkaria Commission (1983)

4. National Commission to Review the Working of the Constitution (2000)

2. The sales tax you pay while purchasing a toothpaste is a (2014)

1. Tax imposed by the Central Government

2. Tax imposed by the central Government but collected by the State Government.

3. Tax imposed by the State Government but collected by the Central Government.

4. Tax imposed and collected by the State Government.