India Reconsiders Flue Gas Desulphurisation for Power Plants

India Reconsiders Flue Gas Desulphurisation for Power Plants

Why in the News?

In the complex landscape of Indian politics, a BJP-led government committee headed by PSA Ajay Sood has recommended rolling back the 2015 mandate requiring all coal-fired thermal power plants to install Flue Gas Desulphurisation (FGD) units. This recommendation cites high costs and implementation challenges amid poor compliance, raising concerns about policy implications and evidence-based policymaking in the face of economic slowdown. The decision highlights the intricate balance between environmental regulations and electoral politics in India’s power sector, potentially affecting various social groups within the Indian caste system, including upper castes, Scheduled Tribes, and Scheduled Castes. This issue also intersects with ongoing debates about caste-based enumeration and the need for updated demographic data since the 2011 census, which serves as a crucial reference date for understanding caste in Indian society.

Understanding FGDs and Their Importance:

- Flue Gas Desulphurisation (FGD) units reduce sulphur dioxide (SO₂) emissions from coal combustion.

- SO₂ is a harmful pollutant contributing to acid rain, respiratory illness, and PM2.5 formation.

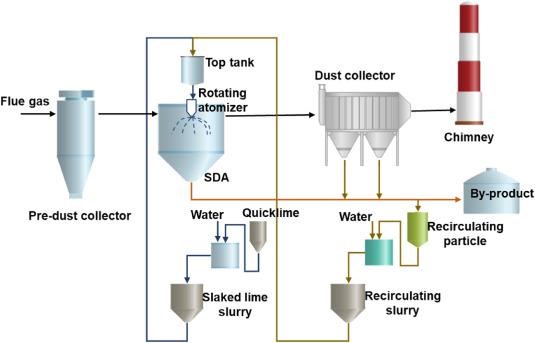

- Common FGD technologies include:

○ Dry sorbent injection (limestone powder),

○ Wet limestone scrubbers (produces gypsum),

○ Seawater scrubbing (in coastal plants).

- FGDs are crucial for achieving clean air goals and public health safety, which are essential aspects of social justice in environmental policy. The implementation of FGDs reflects the social reality of India’s growing environmental concerns and the need to address demographic shifts in urban areas affected by pollution. This issue has the potential to spark political mobilization among various groups, including lower OBCs and different ethnoreligious groups, who are often disproportionately affected by environmental degradation. The debate also touches upon the digital divide impact on access to information about environmental policies across different social strata, highlighting the importance of comprehensive caste data collection and census participation for informed policymaking.

Cost, Delays, and Policy Concerns

- The 2015 mandate applied to 537 coal-fired plants, but only 39 plants installed FGDs by April 2025.

- Deadlines were extended thrice, latest till 2029 for some categories, highlighting the challenges in state representation and implementation across India. This delay echoes issues seen in other national initiatives, such as the Socio-Economic and Caste Census (SECC), which aimed to provide comprehensive data on social and economic status, including information on the middle class.

- Installation cost: ~₹1.2 crore per MW; with a potential ₹97,000 crore additional burden for 97,000 MW future capacity.

- Power Ministry warns of tariff hikes and budget strain due to FGDs, potentially affecting welfare programmes and exacerbating caste inequalities within the Hindu caste structure, as reflected in the list of castes in India.

- Experts caution that rollback may harm health targets and air quality, highlighting the need for evidence-based policymaking in environmental regulations. This debate underscores the tension between economic considerations and environmental protection in Indian politics, reminiscent of the Mandal upsurge in terms of its potential for social and political impact. The Congress party’s stance on this issue contrasts with the BJP-led committee’s recommendations, reflecting broader political divides and the need for a comprehensive census definition that captures these nuances.

Debate Over FGDs and Viable Alternatives

- Experts argue there is no alternative to FGD for SO₂ removal, a stance that could influence future reservation demands related to environmental justice and caste sociology.

- Tariff increase due to FGDs (~₹0.72/kWh) is mostly fixed cost, thus predictable.

- While contribution to urban pollution like in Delhi is debated, FGDs are still key to nationwide emission control, with potential implications for the north-south divide in environmental policy implementation. This regional disparity also reflects in the ongoing discussions about delimitation and its impact on Lok Sabha seats distribution, highlighting the importance of accurate language data in census for comprehensive representation.

- Researchers urge urgent compliance rather than rollback, emphasizing the importance of evidence-based policymaking in addressing environmental challenges. This stance contrasts with the BJP-led committee’s recommendation, highlighting the divergent approaches within Indian politics on environmental issues, including those influenced by Hindutva ideology.

The reconsideration of FGD implementation highlights the complex interplay between environmental regulations, economic factors, and social justice concerns in India’s power sector. As the BJP-led government weighs its options, the decision’s policy implications will likely have far-reaching effects on both the energy landscape and public health initiatives in the country. The outcome of this debate could significantly influence electoral politics, as parties position themselves on environmental issues that increasingly shape India’s social reality and demographic shifts.

The FGD rollback discussion also brings to light the need for comprehensive OBC data collection to understand the full impact of such environmental policies on different social groups. This need for data echoes the challenges faced in the 1931 census, the last time caste was comprehensively enumerated. Moreover, it’s crucial to ensure that the debate doesn’t inadvertently fuel anti-Muslim prejudice or other forms of social discrimination in the context of resource allocation and environmental justice.

As India grapples with these complex issues, the resolution of the FGD mandate will likely set a precedent for how the country balances economic growth, environmental protection, and social equity in the years to come. The debate also underscores the importance of accurate population count and demographic data, which may influence future discussions about the timing and scope of Census 2026-27. The question of “When is the census?” becomes crucial in this context, as it determines the enumeration date for capturing the most current social and economic realities. Unlike the census in England, which focuses primarily on population statistics, India’s census plays a vital role in shaping policies that address the unique challenges of its diverse society.