INDIAN THEATRE

Introduction

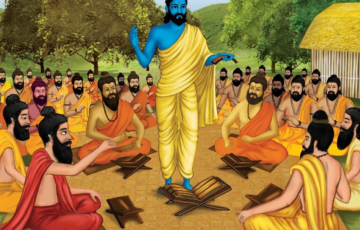

- The roots of Indian theatre extend over 5000 years, and its earliest documented treatise on dramaturgy originated in India. Authored by Bharat Muni, Natya Shastra is recognized as the foundational text or sacred scripture of theatre, dating its composition between 2000 BCE and the 4th Century CE.

- In India, theatre evolved from a narrative form, incorporating recitation, singing, and dancing as integral elements of the theatrical experience. This early emphasis on narrative elements inherently distinguished Indian theatre as inherently theatrical from its very beginning.

- Consequently, Indian theatre seamlessly weaves together a diverse array of literature and fine arts into its physical presentation. This amalgamation encompasses literature, mime, music, dance, movement, painting, sculpture, and architecture, collectively referred to as ‘Natya’ or Theatre in English.

Classical Sanskrit Theatre

The Sanskrit theatre stands as the earliest form of theatrical expression in India, emerging after the developments of Greek and Roman theatre but predating theatrical progress in other Asian regions. Its origins can be traced between the 2nd century BCE and the 1st century CE, flourishing from the 1st century CE to the 10th century—a period characterized by relative peace in India, marked by the creation of numerous plays.

In ancient India, plays typically fell into two categories:

- Lokadharmi: This involved realistic depictions of daily life and human behavior on stage, emphasizing the natural presentation of objects.

- Natyadharmi: This form employed conventional stylized gestures and symbolism, considered more artistic than realistic.

Famous Sanskrit Playwrights:

- Asvaghosa: Authored one of the earliest plays, “Sariputraprakarana,” a humorous yet profound work espousing Buddhist teachings.

- Bhasa: A playwright with thirteen surviving works, including the well-known “Swapanavasavadatta,” drawing themes from the Ramayana, Mahabharata, Puranas, and semi-historical tales.

- Sudraka: Renowned for “Mricchakatika,” which introduced an element of conflict uncommon in Sanskrit drama, featuring a hero, heroine, and a villain.

- Kalidasa: Widely known as one of the “nine jewels” in Vikramaditya’s court, left a lasting legacy with plays like “Malavikagnimitra,” “Vikramorvashi,” and “Shakuntalam.”

- Bhavabhuti: A later playwright from the classical period, known for “Uttaramcharitra,” considered the best dramatic play of its time.

- Others: Shudraka, Harsha, Visakhadatta, and Bhavabhuti were notable playwrights contributing significantly to Sanskrit drama.

Types of Sanskrit Plays:

In the classical Sanskrit tradition, plays were categorized into ten types, with “Nataka” and “Prakarna” being the most prominent. Notable works like “Swapanavasavadatta,” “Uttaramcharitra,” and “Shakuntala” belong to the Nataka category.

Elements of Sanskrit Play:

Sanskrit plays followed a ritualistic progression:

- Pre-Play Rituals (Purva-ranga): Included performances of music and dance behind the curtain.

- Worship (Puja): The Sutradhara and assistants worshiped the presiding deity to ensure success for the production and good luck for the actors.

- Prologue: The leading actress opened the play with a prologue, introducing the time, place, and playwright.

Decline of Sanskrit Theatre:

Several factors contributed to the decline of Sanskrit theatre:

- Shift to Poetry: Playwrights turning toward poetry diminished the popularity of dramatic works in favor of lyrical writings.

- Rigid Orthodoxy: Creative constraints, coupled with orthodoxy, limited the space for new playwrights, prompting them to explore alternative forms.

- Religious Confinement: The confinement of Sanskrit theatre to religious spheres also played a role in its decline.

- Muslim Invasions: The invasion of Muslim rulers further marginalized Sanskrit theatre, leading to its eventual decline.

Folk Theatre

Folk Theatre in India

- Folk theatre in India is a vibrant and diverse cultural tapestry, intricately weaving together elements from music, dance, pantomime, versification, epics, ballad recitation, and visual arts. Rooted deeply in native culture, it transcends formal constraints and serves as a potent medium for interpersonal, inter-group, and inter-village communication. This art form, entrenched in local identity and social values, plays a pivotal role in disseminating cultural messages and fostering awareness among diverse communities.

Emergence of Folk Theatre:

- The 15th-16th century witnessed the forceful emergence of folk theatre across various regions in India. Initially rooted in devotion and centered around religion, local legends, and mythology, it gradually evolved into a more secular form. Themes expanded to include folk stories of romance, valor, and biographical narratives of local heroes.

Classification of Folk Theatres:

- Indian folk theatre broadly falls into two categories—religious and secular—giving rise to Ritual Theatre and Theatre of Entertainment, respectively. These coexisting forms influence each other, showcasing diverse theatrical styles. From narrative and vocal performances like Ramlila, Rasleela, Nautanki, and Swang to dance dramas such as Kathakali and Krishnattam in the south, and song-centric styles like Khyal, Maach, Nautanki, and Swang in the north, each region contributes its unique customs, execution, staging, costume, makeup, and acting styles.

- For instance, the Jaatra of Bengal, Tamasha of Maharashtra, and Bhavai of Gujarat emphasize dialogues and comedy, while puppet theatres like Shadow, Glove, Doll, and String puppets exhibit distinct forms across states.

Influence in Classical and Folk Dance:

Dramatic elements are not confined to standalone theatre; they are intricately woven into solo forms of Indian classical dance, including Bharat Natyam, Kathak, Odissi, and Mohiniattam.

- Folk dances such as Gambhira, Purulia Chhau, Seraikella Chhau, and Mayurbhanj Chhau also integrate dramatic content. Moreover, ritual ceremonies, especially in Kerala, incorporate dramatic components in performances like Mudiyettu and Teyyam.

Famous Folk Theatres:

Theatres of Northern India

Bhand Pather,

A traditional theatre form from Kashmir, stands out among the notable folk theatres in India. It uniquely combines dance, music, and acting, accompanied by instruments like Surnai, Nagaara, and Dhol. Held in open spaces with no predetermined scripts, Bhand Pather celebrates the lives of rishis (Sufi sages), illustrating its secular character and innovative nature.

Saang/Swang:

- Saang/Swang, an enchanting folk dance-theatre form, unfolds its vibrant expression in the cultural landscapes of Rajasthan, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, and the Malwa region of Madhya Pradesh. Acknowledged as one of India’s oldest folk theatre traditions, Saang/Swang intricately weaves itself into the diverse cultural fabric of these regions.

- This captivating form of artistic expression is marked by two distinctive styles: Rohtak and Haathras, each contributing a unique essence to the rich tapestry of Saang/Swang. These styles showcase regional nuances and distinctive flavors, adding depth to this ancient tradition.

- Beyond being a mere performance, Saang/Swang is a cultural phenomenon that has profoundly influenced the evolution of other folk dance-theatre forms. Both Nautanki and Tamasha have drawn inspiration from its roots, evolving into distinctive art forms that spread their own unique charm while preserving the fundamental essence of this timeless folk dance-theatre tradition. The echoes of Saang/Swang resonate through the realm of folk arts, narrating stories of the past, celebrating the present, and securing its enduring legacy for generations to come.

Nautanki

- Nautanki, deeply ingrained in the cultural tapestry of Uttar Pradesh, flourishes as a traditional theatre form, showcasing its vibrant expression in prominent centers like Kanpur, Lucknow, and Haathras. The verses of Nautanki, crafted in meters such as Doha, Chaubola, Chhappai, and Behar-e-tabeel, embody a dynamic fusion of rhythm and expression.

- Initially exclusive to male performers, Nautanki has evolved, with active participation from women, injecting fresh perspectives and dimensions into this time-honored tradition. Notable figures like Gulab Bai of Kanpur have made significant contributions to the innovation and enrichment of Nautanki.

Raasleela

- Raasleela, an exclusive theatrical tradition of Uttar Pradesh, revolves around the timeless legends of Lord Krishna. Originating from the scripts of Nand Das, these plays intricately weave prose dialogues with melodious songs and vivid scenes, portraying the playful escapades of Krishna.

Maach

- Maach, a traditional theatre form in Madhya Pradesh, encompasses both the stage and the play itself. Songs take center stage in Maach, interwoven with dialogues known as “bol” and rhymed narrations termed “vanag.” The tunes, referred to as “rangat,” create a melodious backdrop, enhancing the captivating essence of this theatre tradition.

Ramman

- Ramman, an annual celebration in the Baisakh month (April) in Chamoli district, Uttarakhand, is a cultural extravaganza blending theatre, music, historical reenactments, and traditional tales. The mask dance, exclusively performed by the Bhandaris of the Ksatriya caste, adds a distinctive flair to this vibrant event. Recognized by UNESCO on the Representative List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, Ramman stands as a testament to the rich cultural heritage of Uttarakhand.

Ramlila

- Ramlila, a theatrical spectacle performed during the Dussehra festival in Uttar Pradesh, unfolds over ten days, culminating on Dussehra. Commemorating the triumph of Lord Rama over the forces of evil embodied by Ravana, Ramlila features continuous recitation of the Ramayana, complemented by dance, music, mime, Abhinaya, and poetry—a captivating blend that resonates with enthusiastic and religious audiences.

Kariyala

- Kariyala, an open-air folk theatre in Himachal Pradesh, particularly popular in Shimla, Solan, and Sirmour districts, is known for its entertaining and satirical nature. Addressing social issues and bureaucracy with sharp and pungent satire, Kariyala boldly depicts various shades of humor, making it a distinctive and engaging folk theatre tradition in Himachal Pradesh.

The Theatrical Traditions of Eastern India

Ankia Nat

- Ankia Naats, a genre of one-act plays, grace the stages of Assam. Revered as the brainchild of the medieval saint and reformer, Srimanta Sankardeva, these plays unfold in a particular presentation known as Bhaona. Bhaona productions, incorporating live instruments, singers, dance, and elaborate costumes, create a mesmerizing spectacle. The Sutradhara, a crucial figure, plays a multifaceted role, reciting slokas, singing, dancing, and providing explanations in prose for every act.

Oja-Pali

- Oja-Pali, a traditional folk dance drama originating from Assam, evolved from the Kathakata tradition. Performed in groups, it features an Oja leading the performance, accompanied by four or five palies who contribute to the continuous rhythm with cymbals. Some believe that Srimanta Sankardeva drew inspiration from Ojapali in creating his Ankiya Bhaona.

Jatra

- Jatra, musical plays performed at fairs in honor of gods, religious rituals, and ceremonies, took root and flourished in Bengal. Influenced by Chaitanya, the Krishna Jatra gained popularity, eventually encompassing worldly love stories. Initially musical, dialogues were later incorporated, with actors describing changes of scene and locations themselves.

Bidesia

- Bidesia, the folk theatre of Bihar, tells the poignant story of a man leaving his village and family in search of employment. Founded by Bhikhari Thakur, this primarily musical theatre uses existing Bhojpuri folk songs and tunes for exchanges. The enduring popularity of Bidesia in Bihari villages resonates with the reality of rural life, where men migrate to cities for livelihood, leaving their families behind.

Prahlad Natak

- Originating in Ganjam district of Odisha, Prahlad Natak is a folk theatre with a unique enactment called ‘Danda,’ posing a challenge for new learners. Focused on the myth of Narasimha, Vishnu’s man-lion avatar, Prahlad Nataka employs vocal and instrumental music to intensify its impact. Enriched by traditional Odissi music, the performance combines dialogue and music to convey emotive intent.

Suanga

- Suanga, a musical folk theatre, known as masque or farce, was prevalent in coastal Odisha until the early twentieth century. Its techniques have also influenced the spectacular Prahlada Nataka, showcasing the rich cultural tapestry of the region.

Theatre Traditions of Southern India

Dashavatar

- Dashavatar stands as the quintessence of theatrical expression in the Konkan and Goa regions. In this art form, performers embody the ten avatars of Lord Vishnu, the deity synonymous with preservation and creativity. Through meticulous stylized make-up and masks crafted from wood and papier-mache, these avatars—Matsya (fish), Kurma (tortoise), Varaha (boar), Narsimha (lion-man), Vaman (dwarf), Parashuram, Rama, Krishna (or Balram), Buddha, and Kalki—come to life on the stage.

Krishnattam

- Krishnattam, the folk theatre of Kerala, traces its roots back to the 17th century CE under the patronage of King Manavada of Calicut. Unfolding across eight plays performed on consecutive days, this theatrical narrative delves into various episodes from the life of Lord Krishna. The plays—Avataram, Kaliamandana, Rasa krida, Kamasavadha, Swayamvaram, Bana Yudham, Vivida Vadham, and Swargarohana—chronicle Lord Krishna’s birth, childhood pranks, and triumphant battles against evil.

Mudiyettu

- Mudiyettu, a traditional folk theatre form of Kerala, springs to life during the month of Vrischikam (November-December). Often performed in Kali temples, it serves as an offering to the Goddess, depicting the victory of goddess Bhadrakali over the asura Darika. The characters in Mudiyettu—Shiva, Narada, Darika, Danavendra, Bhadrakali, Kooli, and Koimbidar (Nandikeshvara)—adorn elaborate make-up.

Theyyam

- Theyyam, an immensely popular folk theatre form in Kerala, derives its name from the Sanskrit word ‘Daivam,’ signifying God. Conducted by various castes to appease and worship spirits of ancestors and folk heroes, Theyyam is known for its colorful costumes and awe-inspiring headgears (mudi), reaching heights of nearly 5 to 6 feet. Crafted from arecanut splices, bamboos, leaf sheaths of arecanut, and wooden planks, dyed in vivid colors using turmeric, wax, and arac, these headgears add to the spectacle.

Koodiyaattam/ Kuttiyaattam

- Koodiyaattam, one of Kerala’s oldest traditional theatre forms rooted in Sanskrit traditions, involves characters like Chakyaar (actor), Naambiyaar (instrumentalists), and Naangyaar (female roles). The protagonists, the Sutradhar or narrator and the Vidushak or jesters, are distinctive. Emphasizing hand gestures and eye movements, this dance and theatre form has earned UNESCO recognition as a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity.

Yakshagaana

- Yakshagaana, Karnataka’s traditional theatre form, draws inspiration from mythological stories and Puranas. Popular episodes from the Mahabharata and Ramayana come alive on stage, including Draupadi swayamvar, Subhadra vivah, Abhimanyu vadh, Karna-Arjun yuddh, Raajyaabhishek, Lav-kush Yuddh, Baali-Sugreeva yuddha, and Panchavati.

Therukoothu

- Therukoothu, literally translating to “street play,” stands as Tamil Nadu’s most popular form of folk drama. Frequently performed during annual temple festivals to ensure a rich harvest, it revolves around a cycle of eight plays based on the life of Draupadi. Kattiakaran, the Sutradhara of Therukoothu, conveys the play’s essence to the audience, while Komali entertains with buffoonery.

Burrakatha/ Harikatha

- Burrakatha, a storytelling technique prevalent in villages of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, and Tamil Nadu, involves one main performer and two co-performers. This narrative entertainment encompasses prayers, solo drama, dance, songs, poems, and jokes, covering topics ranging from Hindu mythological stories to contemporary social problems. A variant known as Harikatha or Katha Kalakshepa focuses on tales of Lord Krishna, other deities, and saints.

Veedhi Natakam

- Veedhi Natakam, translating to “street play,” stands as Andhra Pradesh’s most popular folk theatre form. These plays, performed in open spaces, were enacted by Bhagathas, devotees of Bhagwan, and were sometimes referred to as Veedhi Bhagavathams. This tradition celebrates devotion to Bhagwan, with plays bringing divine tales to life in the open air.

Theatrical Traditions of Western India

Bhavai

- Bhavai, a traditional theatre form originating from Gujarat, has its cultural roots deeply embedded in the regions of Kutch and Kathiawar. Accompanied by a diverse array of musical instruments, including bhungal, tabla, flute, pakhaawaj, rabaab, sarangi, anjeera, and more, Bhavai stands out for its unique synthesis of devotional and romantic sentiments. This rare blend creates a captivating performance that resonates with the audience.

Tamaasha

- Tamaasha, a traditional folk theatre form that originated in Maharashtra, has undergone an evolutionary journey from folk traditions like Gondhal, Jagran, and Kirtan. Setting itself apart from other theatrical forms, Tamaasha places the female actress, known as Murki, as the central exponent of dance movements in the play. With the incorporation of classical music, lightning-speed footwork, and vivid gestures, Tamaasha provides a dynamic canvas for portraying a spectrum of emotions through dance.

Modern Indian Theatre

- Modern Indian theatre effortlessly blends three distinct traditions: the Sanskrit theatre tradition, folk theatre tradition, and the influences of Western theatres. Notably, the infusion of Western theatrical elements stands out as a defining feature of modern Indian theatre.

Origin of Modern Indian Theatre

- The genesis of modern Indian theatre aligns with the British arrival in India. As the British established vital trade and administrative centers in Calcutta, Bombay, Surat in the east, and Madras in the south, they introduced theatres for entertainment.

- In 1765, Levdef, a gentleman of Russian origin, laid the groundwork for modern Indian theatre by establishing the Bengali Theatre.

- Early performances, featuring condensed versions of plays like “Disguise” and “Love is the Best Doctor,” marked the initiation of this theatrical movement over two centuries ago. Inspired by Levdef, affluent drama enthusiasts began organizing shows in their residences, lawns, and gardens, leading to the establishment of numerous theatres.

- With a growing interest in theatrical productions, the inevitability of commercial play viewing emerged. This resulted in the formation of theatrical companies, with Parsi theatrical companies taking the forefront. These companies not only toured various provinces, generating revenue but also played a pivotal role in popularizing plays by adapting them into Indian languages.

The Rise of Parsi Theatre

- The first Parsi Theatre company, “Pārsī Nāṭak Maṇḍali,” debuted with the play “Roostum Zabooli and Sohrab” in 1853, followed by productions like “King Afrasiab and Rustom Pehlvan” and “Pādśāh Faredun.” The popularity of Parsi theatre skyrocketed, and by 1860, Mumbai alone boasted over 20 Parsi theatre groups. These companies not only entertained audiences but also played a pivotal role in bridging cultural gaps by scripting plays in Indian languages, making significant contributions to the evolution of modern Indian theatre.

Salient Features of Modern Indian Theatre

Modern Indian theatre embodies several distinctive features:

Predominant Influence of Western Notions of Drama:

- The impact of Western notions of drama is prominently evident in modern Indian theatre, shaping presentation, storytelling techniques, and dramatic structures.

Shift from Happy Endings to Tragic Endings:

- Diverging from the ancient Indian tradition, which favored plays with happy conclusions, modern Indian theatre witnesses a shift toward tragic endings, aligning with Western dramatic traditions.

Impact of Indian Social Developments:

- Modern Indian theatre is a response to significant social developments in India, particularly the processes of modernization and the Renaissance. This dynamic interplay is reflected in the artistic expressions within the realm of theatre.

Evolution of Thematic Content:

- Initially anchored in historical and mythological themes, modern Indian plays undergo thematic evolution. Over time, social and political themes gain prominence, and the integration of elements from classical Sanskrit theatres and folk traditions contributes to a rich diversity of themes.

Incorporation of Traditional Elements:

- As modern Indian theatre progresses, it assimilates elements from classical Sanskrit theatres and folk traditions. For example, Parsi theatres emphasize music, songs, and dances, drawing inspiration from traditional folk plays. Post-independence theatre continues this integration while maintaining a realist foundation from Western traditions.

Experimentation in Theatrical Devices:

- Renowned playwrights, including Badal Sarkar, Shambhu Mitra, Vijay Tendulkar, B.V. Karant, Ibrahim Alkazi, Girish Karnad, and Utpal Dutt, lead experimentation with theatrical devices. Their innovations play a pivotal role in the dynamic evolution and diversification of modern Indian theatre.

Modern Indian Drama and Nationalism:

- In the realm of modern Indian drama, a compelling trend emerged as nationalism intertwined with contemporary social realities. A pioneering work in this genre is Dinabandhu Mitra’s “Neel Darpan,” composed in Bengali. Focused on the coerced cultivation of indigo imposed on native planters by British imperialism, this play not only vividly depicted prevailing social conditions but also symbolized a growing consciousness of nationalism.

- Similarly, Assamese playwrights, including Padmanath Gohai Barua (“Lochit Barfukan”), Lahshmikant Bejbarua (“Ckakradhwaj Singhj”), and Bimlanand Barua (“Sharai Ghat”), conveyed potent nationalist sentiments in their works. In Tamil, Pavler contributed nationalist plays like “Khadrin Verdri” and “Desheeya Koti.” Malayalam witnessed the continuation of the nationalist tradition through the works of V.T. Bhattiripad, K. Damodaran, Govindan, Ittasheri, and S.L. Puran, among others.

- In Hindi, Bharatendu Harishchandra pioneered nationalist satires with plays such as “Bharat Durdasha,” “Bharat Janani,” and “Andher Nagri.” Jai Shankar Prasad later carried this tradition forward to its culmination.

- During the 19th century, Indian intellectuals recognized that India’s decline was not solely attributed to foreign rulers but also rooted in prevalent social evils and superstitions. Plays from this era aptly reflected this understanding, with playwrights directing their criticism toward Indians blindly imitating Western ideals. The focus of these plays extended to societal issues such as the caste system, child marriage, dowry, false notions of pride and prestige, prostitution, untouchability, and various other social maladies. This theatrical exploration served as a poignant mirror, reflecting the multifaceted realities of Indian society during that period.

Post-Independence Plays:

- The post-independence era brought forth significant changes in both the style and content of Indian plays. The aftermath of the Second World War and the partition of the sub-continent profoundly impacted Indian society, challenging the optimism that accompanied the attainment of independence.

- The rapid changes induced by science and industrialization left an indelible mark on Indian plays, influencing the values of the people.

- A notable transformation was the increased accessibility of plays written in foreign languages other than English to India. Works by Brecht from Germany, Gogol and Chekhov from Russia, and Sartre from France became influential, shaping the writing and staging of new plays. This trend was evident in the works of Badal Sarkar in Bengali, Vijay Tendulkar in Marathi, and Girish Karnad in Kannada. The era was characterized by receptivity to new experiments, departing from the earlier practice of writing five-act plays with numerous scenes in one act. This evolved to three acts and eventually to a single act, enhancing viewer continuity and pleasure.

- Historical plays in the pre-independence period often focused on invoking national pride. However, post-independence historical plays sought to understand and analyze history from fresh perspectives. Notable examples include Uttam Barua’s “Varja Fuleshwari” in Assamese, P. Lankesh’s “Sankranti” in Kannada, Girish Karnad’s “Tughlaq” in Hindi, Vijay Kumar Mishra’s “Tat Niranjan” in Oriya, Mohan Rakesh’s “Ashadh Ka Ek Din” in Hindi, Jagdish Chandra Mathur’s “Pahla Rqja” in Hindi, and Sant Singh Sekhon’s “Mohu Sar Na Kai” in Punjabi.

- In the post-independence era, the mythological form was employed to portray complex human emotions and dilemmas. The focus on social plays persisted, expanding to encompass new social problems and themes.

- Themes such as increasing economic disparity, resulting frustrations, the plight of women in society, the despondency of the dalits and the depressed, Hindu-Muslim relations, the miseries of rural life, dehumanization of city life, hypocrisy of the middle class, and the clash between new and old values dominated the thematic content of the new social plays.