INDIAN PAINTING

Introduction

- The progression of Indian paintings not only underscores artistic excellence but also serves as a visual record of the unfolding socio-cultural dynamics over centuries. The scarcity of early instances, partially attributed to climatic conditions, accentuates the vulnerability of tangible artifacts, consequently enhancing the value of the surviving pieces.

- During ancient times, Indian paintings graced the walls of temples and caves, recounting stories from epics and scriptures. These visual narratives operated as a medium of communication, disseminating knowledge and inspiration within communities. The medieval era witnessed the flourishing of miniature paintings, distinguished by intricate detailing and vibrant colors, illustrating a diverse array of themes from courtly life to religious narratives.

- As India transitioned into the modern era, its paintings experienced a rebirth, influenced by both indigenous traditions and exposure to global art movements. Artists embraced novel mediums and styles, contributing to the diversification of the country’s artistic expression. Despite the challenges presented by evolving times and climates, the enduring resilience of Indian paintings solidifies their role as an indispensable element in the intricate tapestry of the nation’s cultural heritage.

- Indian paintings embody an ongoing dialogue between the past and present, seamlessly connecting historical epochs and serving as a visual testament to the enduring spirit of creativity despite environmental challenges.

Principle of Paintings

- Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism emerged as pivotal religious traditions in India, acting as deep wellsprings of inspiration for artists seeking to capture the profound essence of these spiritual ideologies. The trajectory of Indian paintings, intricately interwoven with the nation’s rich history and cultural tapestry, has been profoundly shaped by the diverse influences of these religions. Within the realm of esteemed Indian paintings, one encounters a dynamic portrayal of spiritual themes, noble ideals, and communal beliefs, embodying the intrinsic values inherent to these philosophical traditions.

- In the third century AD, Vatsyayana, through his seminal work Kamasutra, expounded upon the six foundational shadanga or principles of Indian painting, laying the groundwork for a methodical approach to artistic expression.

- These principles encapsulated the multifaceted aspects of artistic creation:

- Rupabheda – Various Forms: This principle championed the exploration and representation of diverse forms, urging artists to delve into a plethora of shapes and structures to convey a comprehensive visual narrative.

- Lavanyayoganam – Emotional Immersion: Emphasizing the significance of emotional depth, this principle implored artists to infuse their creations with profound sentiments, fostering a visceral connection between the artwork and the viewer.

- Varnikabhanga – Combining Colors for Modeling Effects: Addressing the technique of amalgamating colors to achieve three-dimensional effects and modeling, this principle underscored the mastery of color as a tool for instilling depth and realism in artistic representations.

- Pramanam – Proportion of Object or Subject: This principle centered on maintaining proportion and balance in the portrayal of objects or subjects, ensuring a harmonious composition that resonated with aesthetic sensibilities.

- Sadrisyan – Portrayal of Subject’s Likelihood: Encouraging the realistic depiction of subjects, this principle urged artists to capture the essence of portrayed individuals or scenes with authenticity and precision.

- Bhava – Use of Color to Create Lustre and Gleam: Highlighting the emotive power of color, this principle guided artists in using color to evoke specific moods, infusing their creations with vibrancy, and creating a sense of luminosity and brilliance.

- These six principles served as a sturdy foundation for Indian painters, providing not only a framework for mastering the technical aspects of art but also incorporating the profound spiritual and cultural elements that defined the artistic panorama of ancient India.

Pre-Historic Painting of India

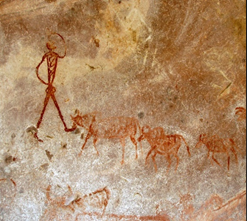

- Artistic creations from ancient times, harking back to prehistoric eras, found their canvas predominantly on rocks, and these rock engravings are commonly identified as Petroglyphs. An archaeological breakthrough transpired in the Bhimbetaka caves of Madhya Pradesh between 1957 and 1958, laying bare the inaugural set of prehistoric paintings.

- This discovery has significantly enriched our comprehension of ancient artistic expressions. The notable assembly, dubbed the ‘Zoo Rock Shelter,’ earns its moniker from the diverse array of fauna meticulously depicted. This extensive collection features a wide spectrum of creatures, including elephants, rhinoceroses, cattle, snakes, spotted deer, barasingha, and more.

Discovery of pre-historic rock paintings in India

The revelation of prehistoric rock paintings in India stands as a captivating testament to the artistic expressions of ancient civilizations, providing a mesmerizing window into the rich cultural heritage of the subcontinent. These extraordinary findings are dispersed across various regions, with each site contributing to our understanding of the diverse and creative aspects of early human societies.

- A particularly noteworthy discovery unfolded in the Bhimbetaka caves of Madhya Pradesh during 1957-58, famously dubbed the “Zoo Rock Shelter.” This site revealed a treasure trove of prehistoric paintings, featuring a remarkable array of fauna such as elephants, rhinoceroses, cattle, snakes, spotted deer, and more. The Bhimbetaka paintings offer a chronological panorama, illustrating the evolving artistic styles and themes across different historical periods.

- Maharashtra’s Ajanta and Ellora Caves are celebrated for their ancient rock art, particularly the murals within the Ajanta Caves dating back to the 2nd century BCE. These intricate paintings, embodying a synthesis of Buddhist, Hindu, and Jain influences, serve as a visual narrative of the religious and cultural practices prevalent during that era.

- In Tamil Nadu, the rock art site of Sittanavasal exposes cave paintings dating back to the 7th century. These artworks depict scenes of daily life, religious rituals, and cultural motifs, offering a valuable glimpse into the socio-religious milieu of ancient Tamil civilization.

- Venturing into Uttarakhand, the rock art site of Bhimbet in the Kumaon region has made significant contributions to the exploration of prehistoric art in India. The rock shelters in this area showcase paintings that highlight the creativity and symbolism prevalent in ancient societies.

these discoveries underscore the multifaceted cultural tapestry of ancient India, with prehistoric rock paintings serving as silent witnesses to the beliefs, lifestyles, and interactions of early human communities. These artworks not only showcase the artistic ingenuity of our ancestors but also contribute to unraveling the mysteries of their world and the intimate connection they maintained with the natural and spiritual realms.

Evolution of pre-historic paintings

Upper Paleolithic Period (40,000–10,000 BC):

- In this era, the rock shelter caves boasted walls composed of quartzite, inspiring the use of minerals as pigments in artistic endeavors. Foremost among these minerals was ochre, also known as geru, which was commonly mixed with lime and water to create a diverse range of pigments.

- The artistic palette of Upper Paleolithic artists featured colors derived from ochre, resulting in a spectrum that ranged from white to dark red and green. These pigments were artfully applied to depict large animals such as bison, elephants, rhinos, tigers, and more on the cave walls. The artists leveraged the natural variations in these pigments to convey the diversity and vitality of the depicted fauna, creating a vivid and dynamic representation of the prehistoric world.

- In the portrayal of human figurines, a nuanced approach was adopted. Red pigments took center stage in depicting hunters, infusing their images with a sense of dynamism and vitality reflective of their roles in the ancient community. Conversely, green pigments were often utilized in the representation of dancers, contributing a lively and vibrant element to the depictions of human activities within the cave art. This sophisticated use of colors and minerals not only showcased the artistic prowess of Upper Paleolithic artists but also offered insights into the symbolic and cultural dimensions of their creations, providing a unique glimpse into the ancient world.

Mesolithic Period (10,000-4000 BC):

- Marked by a discernible shift in artistic expression, the Mesolithic Period stands out for its prevalent use of red color in cave paintings, distinguishing it from the preceding Upper Paleolithic Period. During this era, there was a notable shift in artistic focus towards more compact compositions, resulting in a reduction in the size of the paintings compared to the grandeur of the Upper Paleolithic artworks.

- The canvas of Mesolithic cave art often depicted scenes of group hunting activities, providing a vibrant portrayal of the collaborative efforts of ancient communities in securing sustenance. These hunting scenes not only showcased the practical aspects of survival but also hinted at the intricate social dynamics and cooperation prevalent among Mesolithic societies, offering insights into their communal life.

- Beyond hunting scenes, Mesolithic cave paintings frequently captured pastoral activities, with grazing scenes depicting the pastoralist way of life. The depictions of herds and grazing animals served as visual narratives that reflected the symbiotic relationship between early human communities and the animal kingdom, underscoring the significance of domestication and coexistence.

- Riding scenes, a distinctive feature of Mesolithic cave art, shed light on the emergence of new skills and relationships between humans and animals. These scenes illustrated the domestication of animals for transportation, providing glimpses into the evolving nomadic lifestyles of Mesolithic communities and the expanding human-animal partnerships.

- The use of red color in these paintings not only functioned as a visual element but also carried symbolic significance. It potentially conveyed cultural meanings, ritual practices, or communal identity within Mesolithic societies, adding layers of depth to the artistic expressions of the time. The shift towards smaller compositions and the thematic emphasis on hunting, pastoralism, and riding scenes collectively offer a nuanced glimpse into the evolving dynamics of human civilization during this transitional period.

Chalcolithic Period:

- The Chalcolithic Period marked a significant evolution in cave paintings, characterized by an increased use of green and yellow colors. The primary focus shifted towards depicting battle scenes, offering visual narratives that hinted at the evolving dynamics within Chalcolithic societies.

- Prominent paintings from this era often portrayed men riding horses and elephants, some armed with bows and arrows, suggesting a state of preparedness for potential skirmishes. These artworks provide insights into the martial aspects of Chalcolithic communities, potentially reflecting social complexities, power structures, or defensive strategies employed by these ancient societies.

- The Jogimara Caves in the Ramgarh hills of Surguja district, Chhattisgarh, house paintings from the later Chalcolithic period, dated around 1000 BCE. These caves serve as a canvas for the artistry of the time and contribute to our understanding of the cultural and societal developments during this era.

- Narsinghgarh in Madhya Pradesh stands as another significant site with Chalcolithic cave paintings. The depictions of skins of spotted deer left for drying suggest mastery of tanning skills, highlighting the practical aspects of daily life, such as providing shelter and clothing. The paintings also showcase musical instruments like the harp, offering glimpses into the cultural and recreational dimensions of Chalcolithic communities.

- Chhattisgarh, particularly in the district of Kanker, features a variety of caves, including Udkuda, Garagodi, Khairkheda, Gotitola, Kulgaon, etc. These shelters depict human figurines, animals, palm prints, bullock carts, and more, providing insights into a higher and more sedentary type of living during the Chalcolithic period.

- Rock art sites like Ghodsar and Kohabaur in the district of Korea, Chitwa Dongri in Durg district, Limdariha in Bastar district, and Oogdi and Sitalekhni in Surguja district reveal diverse paintings. These sites portray a range of subjects, from Chinese figures riding donkeys to dragons and agricultural scenes, forming a rich tapestry of Chalcolithic artistic expressions.

- In Odisha, Gudahandi Rock Shelter and Yogimatha Rock Shelter stand as prominent examples of early cave paintings, contributing to the regional diversity of Chalcolithic art. These sites offer insights into the cultural nuances and lifestyles of ancient communities in different geographical locations, enriching our understanding of the Chalcolithic period.

| Bhimbetka Rock Paintings

The Bhimbetka Rock Shelters, situated south of Bhopal in the Vidhyan ranges of Madhya Pradesh, have garnered UNESCO World Heritage Site status since 2003, featuring an impressive array of over 500 rock paintings. The site’s antiquity is exemplified by paintings estimated to be 30,000 years old, preserved in the secluded depths of the caves. Encompassing the timeline from 100,000 BC to 1000 AD, the caves showcase layers of paintings from various historical periods, including Upper Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Chalcolithic, early historic, and medieval, with the Mesolithic age contributing the majority.

|

CLASSIFICATION OF INDIAN PAINTINGS

Mural Paintings in India

- A mural, characterized as a substantial image painted or directly affixed to a wall or ceiling, plays a significant role in India’s history, spanning from the 2nd century BC to the 8th-10th century AD. These captivating artworks are discovered in diverse locations such as Ajanta, Bagh, Sittanavasal, Armamalai Cave, Ravan Chhaya Rock Shelter, and the Kailashnath Temple in Ellora Caves. The prevailing themes of these murals primarily revolve around religious narratives, encompassing Buddhism, Jainism, and Hinduism.

Ajanta Caves

Carved in Time: Unveiling the Story of Ajanta Caves

- Deep within the volcanic cliffs of Maharashtra, India, whispers of a magnificent past echo through a symphony of ancient artistry. The Ajanta Caves, sculpted between the 2nd century BC and the 5th century AD, stand as a testament to a thriving civilization, their walls breathing with tales of faith, beauty, and profound wisdom. 29 caves, cradled in a horseshoe embrace, beckon like an invitation to embark on a journey through time.

A Visual Chronicle of Indian Heritage:

- Step into Caves 9 and 10, and you’ll be met by the vibrant tapestry of the Shunga period. Each brushstroke explodes with color, telling stories of everyday life and divine beings in a style both bold and expressive. Travel further, and the walls transform into a testament to the artistic zenith of the Gupta era. In the remaining caves, intricate details and nuanced expressions illuminate scenes from Buddhist lore, royal processions, and celestial dances. But within Caves 1 and 2, echoes of Ajanta’s later chapters resonate, showcasing a softer, more contemplative beauty.

A Canvas of Stories, Etched in Stone:

- These walls are not mere stone; they are canvases breathing life through a mesmerizing blend of murals and fresco paintings. Tempera technique dances with wet plaster, conjuring not only human values and social life but also the essence of each era – in fashions, adornments, and the very air that surrounds the figures. Intricate hand gestures whisper unspoken emotions, while every female figure boasts a unique hairstyle, a testament to the artist’s keen eye for detail. Even animals and birds come alive with emotive expressions, adding depth and intrigue to the narrative.

Jataka Tales and Celestial Beings:

- The canvas of Ajanta is painted with stories of Jataka, tales of Buddha’s past lives as a Bodhisattva. Each scene unfolds like a chapter in a cosmic epic, offering lessons on compassion, selflessness, and the interconnectedness of all beings. Journey through episodes from Buddha’s earthly existence, depicted with both realism and divine grace. Gaze in awe at the celestial dance of various Bodhisattvas, frozen in the graceful tribhanga pose within Cave 1. Vajrapani, Buddha’s embodiment of power, stands guard, his presence emanating from the painted stone. Manjusri, radiating wisdom, and Padmapani, extending a gentle hand of compassion, complete the celestial tableau.

Masterpieces that Whisper Through Time:

- In Cave 16, the Dying Princess mourns, her poignant posture and delicate features a stark reminder of impermanence. Witness King Shibi’s selfless sacrifice for a pigeon in the Shibi Jataka, or learn the perils of ingratitude in the Matri-Poshaka Jataka. Each scene is a masterpiece, a testament to the artistic might and narrative prowess of ancient India.

- Ajanta is not just a collection of caves; it’s a living tapestry woven from stories, emotions, and a deep connection to the divine. It’s an invitation to step into the past, to marvel at the human capacity for beauty, and to carry its whispers through the ages. So, let us embark on this journey together, guided by the brushstrokes of our ancestors and inspired by the echoes of their ancient wisdom.

Bagh and Badami Cave paintings

- The shared stylistic lineage observed in the paintings discovered in the Bagh caves of Madhya Pradesh and those in Ajanta, especially in caves No. I and II, suggests a cohesive artistic tradition. While both sets of paintings belong to the same artistic form, the figures in Bagh exhibit a distinct character, characterized by more tightly modeled features, robust outlines, and a heightened sense of earthly and human essence compared to their counterparts in Ajanta.

- A captivating chapter in the history of Brahmanical paintings unfolds with the discovery of fragments in the Badami caves, specifically in cave No. III, dating back to around the 6th century A.D. Among these fragments, a particularly well-preserved painting of Siva and Parvati has been identified. While adhering to the technical methods of Ajanta and Bagh, the Badami paintings showcase a more refined and sensitive approach to texture and expression in modeling, characterized by softer and more elastic outlines.

- The paintings of Ajanta, Bagh, and Badami collectively epitomize the classical tradition of the North and the Deccan at its zenith. This influential tradition extended its reach to southern regions, as evidenced by centers like Sittanavasal. The paintings found in Sittanavasal, intimately connected with Jain themes and symbolism, maintain fidelity to the same artistic norms and techniques observed in Ajanta. The contours in these paintings are distinctly delineated in dark hues against a light red ground.

- A particularly captivating scene graces the ceiling of the Verandah in Sittanavasal—a large decorative composition of immense beauty. This scene depicts a lotus pool populated with birds, elephants, buffaloes, and a young man engaged in the serene act of plucking flowers, adding an extra layer of aesthetic richness to the artistic legacy of these sites.

Ellora

- Ellora, situated approximately 100 kilometers from the Ajanta caves in the Sahyadri ranges of Maharashtra, stands as an extraordinary archaeological site that witnessed the meticulous excavation of numerous Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain temples directly from the living rock between the 8th and 10th centuries A.D. This expansive complex comprises a total of 34 caves, further categorized into 17 Brahmanical, 12 Buddhist, and 5 Jain caves. The development and evolution of Ellora’s complex unfolded over the period from the 5th to the 11th centuries CE, attributed to the collaborative efforts of various guilds from Vidarbha, Karnataka, and Tamil Nadu.

- A remarkable feature within Ellora is the Kailashnath Temple, a freestanding monolith celebrated for its grandeur. Constructed under the patronage of Rashtrakuta king Krishna I, this temple is dedicated to Lord Shiva and boasts several fragments of paintings adorning its ceiling across different sections.

- Among the noteworthy caves, Cave No. 10 stands out as a prominent Buddhist Chaitya cave, commonly known as Vishwakarma Cave or Carpenter’s Cave. Within this cave, Buddha is depicted seated in Vyakhyana Mudra, with a meticulously carved Bodhi tree positioned at his back.

- Cave No. 14 at Ellora follows the thematic portrayal of “Raavankikhai,” while Cave No. 15 is acknowledged as the Dashavatara Temple. Additionally, the Ellora complex is home to two famous Jain caves—Indra Sabha (Cave 32) and Jagannath Sabha (Cave 33). These caves contribute significantly to the diverse and rich cultural heritage embedded in Ellora’s ancient rock-cut marvels.

Badami

- Badami, once the flourishing capital of the early Chalukyan dynasty reigning from 543 to 598 CE, has left an enduring imprint on history. This significance transcends mere inscriptions, resonating vividly within the confines of Cave No. 4—a testament to the cultural and artistic brilliance of its era.

- The inscription within Cave No. 4, dating back to 578–579 CE, not only extols the cave’s sheer beauty but also bears witness to the dedication of the image of Vishnu within its sacred precincts. Serving as the epicenter of the Chalukyan dynasty, Badami thrived, and this inscription offers a glimpse into the aesthetic and religious sentiments prevailing during that period.

- Within the depths of this cave, a visual narrative unfolds through paintings that capture scenes from palatial life, providing a glimpse into the regal and societal milieu of that era. One tableau, in particular, immortalizes Kirtivarman, the son of Pulakesin I and the elder sibling of Mangalesha, seated majestically within the palace. Accompanying him is his wife, surrounded by feudal lords, all captivated by a mesmerizing dance performance. These paintings not only depict the splendor of the Chalukyan court but also exhibit the artistic finesse of the epoch.

- Stylistically, the paintings of Badami Cave No. 4 resonate with those discovered in Ajanta, echoing sinuously drawn lines, fluid forms, and compact compositions characteristic of the sixth century CE. The maturity and proficiency showcased by the artists of Badami during this era stand as a testament to the cultural renaissance and artistic brilliance that defined the reign of the Chalukyan dynasty.

| Evolution of Mural Painting Across Different Empires

Chola Kings In regions once ruled by the Chalukya kings, the Pallava kings emerged as significant patrons of the arts. Mahendravarman I, adorned with titles like Vichitrachitta (curious-minded), Chitrakarapuli (tiger among artists), and Chaityakari (temple builder), displayed a profound interest in artistic endeavors. Although only fragments of temple paintings initiated under his patronage remain, one notable creation is the gracefully drawn Panamalai figure of a female divinity. The paintings in the Kanchipuram temple, supported by Pallava king Rajasimha, exhibit round and large faces with rhythmic lines and increased ornamentation compared to earlier periods. The depiction of the torso, reminiscent of earlier sculptural traditions, maintains an elongated form. With the rise of the Pandyas, they too became patrons of the arts. Surviving examples include the Tirumalaipuram caves and Jaina caves at Sittanvasal, where veranda pillars showcase dancing figures of celestial nymphs. The firmly drawn contours, painted in vermilion red on a lighter background, present bodies in yellow with subtle modeling. The supple limbs and expressive faces of the dancers reflect the artists’ skill in creative imagination within the architectural context. Executed on the walls surrounding the shrine in the Brihadeshwara temple, these paintings narrate various aspects related to Lord Shiva, portraying him in Kailash, as Tripurantaka, Nataraja, and featuring a portrait of the patron Rajaraja along with his mentor Kuruvar and dancing figures. Kerala Murals During the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries, painters in Kerala developed a distinct pictorial language and technique, selectively adopting stylistic elements from Nayaka and Vijayanagara schools. Drawing inspiration from contemporary traditions like Kathakali and kalam ezhuthu (ritual floor painting of Kerala), they employed vibrant and luminous colors, representing human figures in three-dimensionality. The artists also drew from oral traditions and local versions of the Ramayana and Mahabharata for painted narrations. More than sixty sites, including three palaces—the Dutch Palace in Kochi, Krishnapuram Palace in Kayamkulam, and Padmanabhapuram Palace—feature mural paintings. Notable sites showcasing the mature phase of Kerala’s mural painting tradition include Pundareekapuram Krishna Temple, Panayanarkavu, Thirukodithanam, Triprayar Sri Rama Temple, and Thrissur Vadakkunathan Temple. Vijayanagara Murals The murals at Tiruparakunram, situated near Trichy and dating back to the fourteenth century, represent the early phase of the Vijayanagara style. In Hampi, particularly at the Virupaksha temple, the paintings on the ceiling of its mandapa vividly depict events from dynastic history and narratives from the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. Among the notable panels are representations of Vidyaranya, the spiritual teacher of Bukkaraya Harsha, being carried in a palanquin during a procession, and scenes illustrating the incarnations of Vishnu. Additionally, in Lepakshi, near Hindupur in present-day Andhra Pradesh, one can discover significant examples of Vijayanagara paintings adorning the walls of the Shiva temple. Remaining faithful to tradition, Vijayanagara painters crafted a distinct pictorial language, featuring faces in profile and rendering figures and objects in a two-dimensional manner. The lines in these murals strike a balance between stillness and fluidity, while compositions unfold gracefully within rectilinear compartments. |

Miniature Paintings:

A Brief Overview

- The term ‘miniature’ has its roots in the Latin word ‘Minium,’ referring to red lead paint extensively used in illuminated manuscripts during the Renaissance. Frequently confused with ‘minimum,’ implying small size, miniature paintings boast a rich tradition on the Indian subcontinent. They encompass distinct schools with variations in composition and perspective, distinguished by intricate detailing.

- Miniature paintings adhere to specific size constraints, limiting the canvas to 25 square inches, with the subject occupying no more than 1/6th of the actual size. Notable features include bulging eyes, pointed noses, and slim waists.

Early Miniature Paintings:

In their nascent stage, early miniature paintings were less refined, featuring minimal adornments. Over time, they evolved, incorporating detailed embellishments and reflecting characteristics akin to contemporary miniature art. Dating from the 8th to the 12th centuries, these paintings were often crafted for books or albums, utilizing perishable materials like paper, palm leaves, and cloth.

Prominent Schools of Early Miniature Paintings:

- Pala School of Art: Flourishing during 750-1150 AD, this school made significant contributions to Buddhist manuscripts. Executed on palm leaves or vellum paper, Pala School paintings are identified by sinuous lines and subdued background tones. They typically showcase solitary figures and were favored by adherents of the Vajrayana school of Buddhism.

- Apabhramsa School of Art: Originating in Gujarat and the Mewar region in Rajasthan, this school dominated western India from the 11th to the 15th century. Themes in Apabhramsa paintings often centered around Jainism, later adopted by the Vaishnavism School.

These distinctive schools collectively trace the evolution of miniature paintings, embodying a fusion of cultural influences and artistic refinement across the ages.

Transition Period Miniature

- The arrival of Muslims in the Indian subcontinent during the 14th century marked a transformative period that ushered in a cultural renaissance. Contrary to the notion that Islamic styles completely supplanted traditional painting forms, the Western Indian courts preserved and sustained these traditional styles, resulting in a cultural synthesis.

- In the Southern States of Vijayanagara, a distinctive painting style began to emerge, closely aligning with the Deccan style. This particular style featured a flat application of colors, with dress and human outlines distinctly outlined in black. Facial depictions adopted a three-quarter angle, creating a sense of detachment. The landscapes in these paintings were characterized by abundant trees, rocks, and other elements, consciously avoiding an attempt to faithfully replicate the natural appearance of the subjects.

Miniature Art during Delhi Sultanate: An Artistic Fusion

- The Delhi Sultanate fostered an Indo-Persian style of painting, deeply influenced by Iranian and Jain artistic traditions. Predominantly originating from Mandu in central India and Jaunpur in the east, with additional contributions from the Delhi region and Gujarat in the west, most Sultanate paintings between 1450 and 1550 showcased a unique blend of cultural influences.

- Characteristic features of Delhi Sultanate paintings, rooted in Indian traditions, included depictions of groups in identical poses, narrow decorative bands spanning the width of the paintings, and the use of bright and unconventional colors. The Nimat Nama, a remarkable manuscript from Mandu during Nasir Shah’s reign, stands out among these artworks. This book of recipes portrays the sultan surrounded by attendants preparing various items, reflecting a fusion of Indian painters drawing inspiration from Shirazi models. The paintings within feature thick green swards, pastel background colors, and provincial Persian figural types.

- During this period, another prevalent style known as Lodi Khuladar was followed in many Sultanate-dominated regions between Delhi and Jaunpur. Subsequently, three major styles—Mughal, Rajput, and Deccan—emerged, each borrowing from Sultanate precedents while developing its own distinct identity.

- The paintings of the Delhi Sultanate signify a period of innovation that laid the foundation for the evolution of the Mughal and Rajput schools of art, flourishing from the 16th to the 19th centuries.

Mughal Era Miniature Painting

- During the Mughal era, a distinctive style of miniature painting emerged, blending Persian influences with unique themes, colors, and forms introduced by the Mughal emperors. Court scenes were portrayed with grandeur, often against hilly landscapes, placing a notable emphasis on depicting flowers and animals.

- The focus of Mughal paintings shifted from portraying deities to glorifying the ruler and illustrating aspects of his life. Prominent themes included hunting scenes, historical events, and court-related depictions.

- Renowned for their subtlety and naturalism, Mughal paintings were characterized by their brilliant use of colors. Mughal artists also introduced the technique of foreshortening to Indian painting, allowing objects to be drawn in a way that creates the illusion of proximity and reduced size.

Early Mughal Painters:

- Babur, the founder of the Mughal dynasty, established his reign after a series of wars. Despite having limited time to commission paintings, he is believed to have supported the Persian artist Bihzad, who created illustrations of the Mughal family tree.

- Humayun, a passionate patron of the arts, ascended the throne at a young age. Although interested in paintings and constructing beautiful monuments, his artistic endeavors were interrupted when he lost the throne to Sher Shah Suri and faced exile in Persia.

- During his stay at Shah Tahmasp’s court in Persia, Humayun enlisted the services of two prominent painters, Abdus Samad and Mir Sayyid Ali. Upon reclaiming his throne and establishing the Mughal dynasty in India, he brought these artists back with him. They played a crucial role in infusing Persian influence into Mughal paintings, producing numerous successful illustrated albums.

- Under Akbar’s reign, these artists collaborated on the creation of an illustrated manuscript known as the Tutinama (Tales of a Parrot).

Akbar

- Akbar played a crucial role in establishing a specialized department dedicated to the creation of paintings and the transcription of his documents. This initiative resulted in the formation of a formal artistic studio known as Tasvir Khana, where artists were employed on a salary basis and granted the autonomy to develop their unique styles.

- Regarding paintings as a versatile medium for both education and entertainment, Akbar believed in their capacity to accurately convey the demeanor of subjects. He consistently rewarded painters who excelled in producing lifelike images. Recognizing the talent of Indian artists who had previously served other rulers, Akbar extended invitations for them to contribute to Tasvir Khana, marking the initiation of the ‘Indian influence’ in Mughal paintings.

- Distinctive features of Akbar’s era included paintings featuring three-dimensional figures and a consistent use of foreshortening. Additionally, artists during this period actively advocated for the integration of calligraphy into their works. A notable transformation occurred as popular art evolved into court art, with artists directing their focus toward depicting scenes from court life rather than the lives of the general populace.

- Prominent painters of this period included Daswanth, Basawan, and Kesu. Some of the distinguished illustrated manuscripts created during Akbar’s reign encompassed Tutinama, Hamzanama, Anvar-i-Suhaili, and Gulistan of Sadi.

Jahangir

- The pinnacle of Mughal paintings was attained during the reign of Jahangir. With a naturalist inclination, he favored portraits depicting flora and fauna, creating timeless world classics, particularly in the depiction of birds and animals.

- Jahangir transitioned from illustrated manuscripts to albums, placing a strong emphasis on infusing naturalism into individual portrait painting. A distinctive trend that emerged during this era was the incorporation of ornate margins around the paintings, at times rivaling the intricacy of the paintings themselves.

- Despite being acknowledged as a proficient artist, Jahangir’s major works have not survived, and he maintained his private workshop. The workshop primarily focused on producing miniature paintings, with the most renowned pieces being naturalistic depictions of the Zebra, the turkey, and the cock.

- A prominent artist from Jahangir’s era was Ustad Mansoor, celebrated for his skill in rendering the features of intricately detailed faces. The period also saw the illustration of the animal fable “Ayar-i-Danish” (Touchstone of Knowledge).

Shah Jahan

- Shah Jahan initiated a swift transformation in the nature of Mughal paintings, departing from the naturalistic tendencies of his father and grandfather. Instead, he gravitated towards incorporating artificial elements into the artwork, drawing inspiration from European influences and introducing an artificial sense of tranquility.

- Deviating from the conventional use of charcoal, Shah Jahan discouraged its application, urging artists to opt for pencils in their drawing and sketching pursuits. Additionally, he mandated an increased integration of gold and silver in the paintings, coupled with a preference for brighter color palettes in contrast to the artistic preferences of his predecessors. As a result, the Mughal atelier expanded during his reign, undergoing significant changes in both style and technique.

- Defined by a romantic disposition, Shah Jahan exhibited a aversion to violence and unattractiveness. The subject matter of the paintings shifted towards portraits and a variety of themes such as durbar scenes, processions, festivals, and outings.

Aurangzeb

- Aurangzeb did not actively support the progression of Mughal paintings.

- Artists from the Mughal court relocated to regions like Rajasthan and other kingdoms, carrying the Mughal art-style with them. This artistic style blended with the tastes of their new patrons and local influences, giving rise to a distinct art-style recognized as Provincial Mughal.

- Awadh emerged as a significant center for Provincial Mughal art, where the amalgamation of artistic traditions flourished.

Regional Art Schools

- Even as the Mughal painting style dominated the medieval era, sub-imperial schools cultivated their individuality by nurturing distinctive artistic styles. These schools maintained ties to their Indian heritage and leaned towards vibrant paintings, diverging from the Mughal style’s more naturalistic approach. The array of schools and styles that surfaced during this period included:

Rajasthani School of Painting

- Originating in the Rajputana region, the Rajasthani painting tradition extends from Bikaner to the Gujarat border and from Jodhpur to Gwalior and Ujjain. These artworks primarily explore themes rooted in religion and love, often depicting narratives associated with Lord Rama and Lord Krishna. Common subjects within this tradition include court scenes and royal portraits.

- Marked by bold outlines and vibrant colors, Rajasthani paintings showcase distinctive characteristics. The narrative of Padmavati, as narrated by the poet Malik Muhammad Jaisi, recurrently served as inspiration for Rajput paintings. Additionally, illustrations from the Mahabharata, Bana Bhatta’s Kadambari, and the Panchatantra found artistic expression within this rich tradition.

- The Rajput painting style underwent a unique evolution in various regions, including Bundi, Kota, Jaipur, Mewar, and Kishangarh.

Mewar School of Painting

- The Mewar School of Painting, renowned for its resistance against Mughal dominance, eventually succumbed to Mughal authority during the reign of Shah Jahan. Despite navigating political upheavals, the Rajput kings of Mewar persisted as patrons of the arts, contributing to the development of a distinctive artistic style.

- The refined era of Mewar painting began in 1571 CE, supplanting the earlier ‘Apabhransa.’ This shift was fueled, in part, by the migration of numerous artists from Mandu to Mewar after the Mughals defeated Baj Bahadur, the ruler of Mandu, in 1570.

- The early Mewar paintings bore a significant imprint of Sahibdin, an exceptional 17th-century painter. During this period, Sahibdin devoted his focus to illustrating literary texts such as the Ragamala, the Ramayana, and the Bhagavata Purana. The painting of Ragamala in 1605 A.D. stands as the earliest instance of a series of Mewar paintings.

- Ragamala paintings, distinctive to Rajput miniature art, portray Indian Ragas and Raginis, capturing the mood and time of each Raga through vibrant colors and elegantly attired Nayak and Nayikas, often adorned in contemporary royal attire.

- Following Sahibdin’s passing, the style of Mewari paintings underwent a transformation, shifting towards depictions of life at the Mewar court. Notably, this period featured remarkable ‘tamasha’ paintings, providing unprecedented detail of court ceremonies and city views.

Kishangarh School of Painting

- The Kishangarh School of Painting, nurtured under the patronage of Raja Savant Singh (1748-1757 CE), is celebrated for its distinctive artistic contributions, with the creation of Bani Thani painting standing out prominently.

- Regrettably, only a limited number of Kishangarh miniatures have persevered over time. Many of these extant works are credited to the master painter Nihal Chand, who skillfully translated his master’s lyrical compositions into captivating visual images. Nihal Chand’s artistic creations are characterized by delicately drawn human figures featuring slender bodies and enchanting, uplifted eyes.

- A prevailing notion suggests that the female subjects depicted in ‘Bani Thani’ bear a remarkable resemblance to the character of Radha. These depictions showcase a distinct profile, accentuating lotus-like elongated eyes, thin lips, and a pointed chin. The unique ‘odhni’ or headgear worn by the female figures defines their side profile, becoming an iconic element associated with the Kishangarh School. The school also produced a myriad of paintings illustrating the devotional and amorous connections between Radha and Krishna.

Amber-Jaipur School of Painting

- The Amber-Jaipur School of Painting, intricately linked to the Amber rulers who maintained strong affiliations with the Mughals, emerges as a dynasty known for significant patronage and a profound interest in art collection. Despite their noteworthy contributions, the recognition of the “Amber School” lags behind that of other artistic schools in our collective awareness. A substantial portion of their art collection remains in private hands, largely undisclosed.

- Also acknowledged as the ‘Dhundar’ school, the earliest manifestations of Amber School’s art can be traced back to the wall paintings at Bairat in Rajasthan. Additional instances are visible on the palace walls and mausoleum of Amer Palace in Rajasthan. While some male figures are depicted wearing Mughal-style attire and headgear, the overall visual appeal of the paintings radiates a folk style, lending a distinctive character to the artworks.

- Reaching its zenith in the 18th century under the guidance of Sawai Pratap Singh, this artistic school flourished. Sawai Pratap Singh, marked by profound religious convictions and a fervent advocacy for the arts, played a pivotal role in fostering the prosperity of his suratkhana, the painting department. Within this department, miniatures were meticulously created to depict the Bhagwata Purana, Ramayana, Ragamala, and an array of portraits, seamlessly blending the dual influences of religious devotion and artistic patronage.

Bundi School of Painting

- The Bundi School of Painting, closely associated with the Mewar style, emerged in the regions of Bundi and Kota, with its artistic origins dating back to around 1625 CE. An early and notable example of Bundi Paintings is the Chunar Ragamala, crafted in 1561.

- The rulers of Bundi and Kota were devoted Krishna enthusiasts. In the 18th century, they declared themselves as mere regents, governing on behalf of the god, acknowledged as the true king—a practice also observed in various other centers, including Udaipur and Jaipur. The intriguing relationship between Krishna bhakti and painting in Bundi prompts reflection on the reciprocal influence between the two.

- Bundi paintings depicted a diverse range of themes, encompassing hunting, court scenes, festivals, processions, the lives of nobles, romantic encounters, animals, birds, and episodes from Lord Krishna’s life. The distinctive features of the Bundi school include a preference for lush vegetation, dramatic night skies, a unique portrayal of water with light swirls against a dark background, and vibrant depictions of movement.

- A hallmark of the Bundi style is the depiction of round human faces with pointed noses. The representation of the sky incorporates various colors, often featuring a prominent red ribbon against the backdrop.

Pahari School of Painting

- The Pahari School of Painting is situated in the Pahari region, covering the present state of Himachal Pradesh, adjoining areas of Punjab, Jammu in the Jammu and Kashmir State, and Garhwal in Uttarakhand. This region comprised small states governed by Rajput princes, becoming centers of significant artistic activity from the latter half of the 17th to nearly the middle of the 19th century.

- Within this region, approximately 22 princely states hosted ateliers in their courts, giving rise to the Pahari School of Painting, which can be broadly categorized into two major groups:

- Basholi School

- Kangra School

- Pahari paintings explored themes ranging from mythology to literature, introducing innovative techniques. A distinctive feature of Pahari paintings is their dynamic composition, often featuring numerous figures on the canvas, each characterized by unique movement, composition, color, and pigmentation.

- Notable painters from the Pahari School include Nainsukh, Manaku, and Sansar Chand, who made significant contributions to the artistic legacy of the region.

Basholi School

- Basholi represents the earliest development of painting in the Pahari region, showcasing miniatures from the Rasamanjari series. During its inception, the art form featured expressive faces with a receding hairline and large eyes shaped like lotus petals.

- The Basholi style of painting is characterized by dynamic and bold lines, along with vibrant and intense colors. Primary colors such as red, yellow, and green play a prominent role in these artworks. While borrowing the Mughal technique of painting on clothing, artists in Basholi developed their own distinctive styles and techniques.

- The influence of the Basohli style extended to neighboring states and persisted until the middle of the 18th century. Raja Kirpal Pal, the first patron of this school, commissioned the illustration of Bhanudatta’s Rasamanjari, Gita Govinda, and drawings of the Ramayana.

- Prominent among the artists of this school, Devi Das stands out for his renowned depictions of Radha Krishna and portraits of kings adorned in their livery and white garments.

| Guler School

The Guler school succeeded the final phase of the Basohli style, introducing a new naturalistic and delicate style that departed from the earlier traditions of Basohli art. The paintings from this school exhibit soft and cool colors, and the female figures depicted are notably delicate, with well-modeled faces, small and slightly upturned noses, and intricately detailed hair. |

Kangra School

- The decline of the Mughal Empire, numerous artists trained in the Mughal style migrated to the Kangra region of Himachal Pradesh, attracted by the patronage offered by Rajput Kingdoms. This migration led to the establishment of the Guler-Kangra School of paintings, initially evolving in Guler before reaching Kangra.

- Reaching its pinnacle under the patronage of Raja Sansar Chand, the Kangra School distinguished itself with paintings characterized by sensuality and intelligence, setting it apart from other schools. It represents the third phase of Pahari painting in the last quarter of the 18th century, following the Guler style and retaining its main characteristics, such as delicacy of drawing and quality of naturalism.

- In Kangra paintings, women’s faces in profile feature noses almost in line with the forehead, long and narrow eyes, and a sharp chin. Popular themes included the Gita Govinda, Bhagwata Purana, Satsai of Biharilal, and Nal Damayanti. Love scenes of Krishna were particularly prominent, and the paintings exuded an otherworldly feel.

- An illustrious group of paintings from the Kangra School depicts the ‘Twelve months,’ where artists aimed to convey the impact of each month on human emotions. This emotive style remained popular until the 19th century. The Kangra School served as the parent school to other ateliers that developed in the regions of Kullu, Chamba, and Mandi.

- In Kangra, the Sansar Chand Museum offers a glimpse of prominent Kangra School paintings and serves as a testament to the artistic legacy of the region.

Kullu-Mandi School

- The Kullu-Mandi School is a folk-style painting school located in the Kulu-Mandi area, primarily influenced by local traditions. It is characterized by bold drawing and the use of dark, subdued colors, maintaining a distinct folkish character with occasional influences from the Kangra style. This school has produced a significant number of portraits depicting the rulers of Kulu and Mandi, along with miniatures featuring various themes.

Ragamala Paintings

- Ragamala Paintings constitute a series of illustrative artworks from medieval India based on Ragamala, or the ‘Garland of Ragas,’ portraying different Indian musical Ragas. They serve as a classical example of the integration of art, poetry, and classical music in medieval India.

- Emerging in the 16th and 17th centuries, Ragamala paintings were created in various Indian painting schools, categorized today as Pahari Ragamala, Rajasthan or Rajput Ragamala, Deccan Ragamala, and Mughal Ragamala. Each painting personifies a raga through a specific color, narrating the story of a hero and heroine (nayaka and nayika) in a particular mood.

- Additionally, the paintings elucidate the season and the time of day and night associated with each raga.

- Many paintings in the Ragamala series also identify Hindu deities linked to the respective ragas, such as Bhairava or Bhairavi to Shiva and Sri to Devi. The six principal ragas featured in Ragamala are Bhairava, Deepak, Sri, Malkaush, Megha, and Hindola.

Miniatures in South India

The tradition of creating miniature paintings was already prevalent in South India and developed during the early medieval period. These South Indian miniatures differed from their North Indian counterparts due to the extensive use of gold. Moreover, they focused more on depicting divine creatures rather than the rulers who provided patronage. Some notable schools include:

Tanjore Paintings (renowned for gold coating)

- This style of painting, characterized by bold drawing, shading techniques, and the use of pure and vibrant colors, flourished in Tanjore in South India during the late 18th and 19th centuries.

- Noteworthy for their embellishments with semi-precious stones, pearls, glass pieces, and gold, these paintings are known for their rich, vibrant colors and intricate artistic work.

- The subjects of these paintings predominantly feature Gods and Goddesses, as this art form prospered during a period when magnificent temples were being constructed by rulers of various dynasties.

- The figures in Tanjore paintings are often large, with round and divine faces. Many paintings depict a smiling Krishna in various poses and showcase significant events in his life.

- Under the patronage of Maharaja Serfoji II of the Maratha dynasty, this school reached its zenith, as he was a great supporter of the arts.

While the Tanjore school is still operational, it has diversified its subjects to include birds, animals, buildings, and more in its artistic repertoire.

Mysore Paintings

- The distinctive school of Mysore painting evolved from the artistic traditions of the Vijayanagar period during the reign of the Vijayanagar Kings (1336-1565 CE). Known for their elegance, muted colors, and meticulous attention to detail, Mysore paintings predominantly depict themes related to Hindu gods, goddesses, and scenes from Hindu mythology.

- A noteworthy aspect of Mysore paintings is the inclusion of two or more figures in each artwork, with one figure dominating the composition in terms of size and color. These paintings are characterized by delicate lines, intricate brush strokes, graceful delineation of figures, and the subtle use of vibrant vegetable colors and lustrous gold leaf.

- Gesso work, a distinctive feature of traditional Karnataka paintings, played a significant role in Mysore paintings.

- Gesso refers to a paste mixture of white lead powder, gambose, and glue used as an embossing material and covered with gold foil.

- In Mysore painting, Gesso was employed to depict intricate designs of clothing, jewelry, and architectural details on pillars and arches that typically framed the deities.

Modern Paintings

Company Paintings

- In the colonial era, a unique painting style emerged by blending elements from Rajput, Mughal, and various Indian styles with European influences. This artistic evolution occurred as British Company officers engaged artists trained in Indian traditions, resulting in a fusion of European aesthetics with Indian techniques, commonly known as ‘Company Paintings.’

- Distinguished by the use of water colour and the incorporation of linear perspective and shading techniques, this painting style had its roots in cities such as Kolkata, Chennai, Delhi, Patna, Varanasi, and Thanjavur. Supported by figures like Mary Impey and Marquess Wellesley, numerous artists focused on illustrating the ‘exotic’ flora and fauna of India.

- Notable artists from this school included Mazhar Ali Khan and Ghulam Ali Khan. The influence of this genre persisted until the 20th century.

Bazaar Paintings

- This artistic school was influenced by the European encounter in India, setting itself apart from Company paintings by refraining from the fusion of European techniques and themes with Indian ones. Instead, the Bazaar school drew inspiration from Roman and Greek influences, with painters tasked to replicate Greek and Roman statues.

- Thriving in the Bengal and Bihar regions, this school not only embraced Greco-Roman heritage but also depicted everyday bazaars set against European backdrops. Notably, a popular genre featured depictions of Indian courtesans dancing before British officials.

- While religious themes were part of their repertoire, the portrayal of Indian Gods and Goddesses with more than two axes and elephant faces, resembling Lord Ganesha, was prohibited. This restriction stemmed from the deviation from the European notion of a natural human figurine.

Raja Ravi Varma

|

The Bengal School of Art

- The Bengal School of Art is renowned for its reactionary approach to existing painting styles, employing simple colors as a distinctive feature. Abanindranath Tagore played a pivotal role in the emergence of the Bengal school in the early 20th century with his Arabian Night series, gaining global recognition for its groundbreaking departure from previous Indian painting schools. Abanindranath Tagore aimed to infuse Swadeshi values into Indian art, reducing the influence of Western materialistic styles among artists. Notable works by Abanindranath Tagore include “Bharat Mata” and various Mughal-themed paintings.

- Nandalal Bose, another prominent painter of the Bengal School associated with Santiniketan, made significant contributions to the development of Modern Indian Art. His iconic white-on-black sketch of Gandhi during the Dandi March in the 1930s became an emblematic representation. Bose was entrusted with illuminating the original document of the Constitution of India.

- Rabindranath Tagore, a renowned figure in this school, created unique paintings characterized by dominant black lines that emphasized the subjects. His preference for smaller-sized paintings has led some art historians to draw connections between his paintings and his writings.

- Other notable painters of the Bengal School include Asit Kumar Haldar, Manishi Dey, Mukul Dey, Sunayani Devi, and more.

Cubist Style of Painting

- Derived from the European Cubist movement, the Cubist style of painting involved the deconstruction, analysis, and reassembly of objects. Artists conveyed this process on the canvas through the use of abstract art forms, aiming to achieve a harmonious balance between line and color.

- Cubism, a genuinely revolutionary style of modern art, was developed by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braques. In India, one of the most notable Cubist artists was M.F. Hussain. In his paintings with abstract connotations, Hussain frequently employed the motif of a horse, finding it to be an effective means of depicting the fluidity of motion.

|

Tikuli Art, originating from Bihar, is a distinctive form of artistic expression named after the local term for the “Bindi” worn by women between their eyebrows. This unique tradition involves crafting paintings on hardboard, which is later cut into various shapes. The meticulous process includes applying four to five enamel coats, resulting in a polished surface that enhances the visual allure of the artwork. Beyond its aesthetic appeal, this technique highlights the cultural significance of the Bindi, transforming it into a captivating and symbolic form of art. The amalgamation of traditional symbolism with creative craftsmanship renders Tikuli Art a noteworthy and visually striking contribution to Bihar’s artistic heritage. |

|

Pattachitra Painting, originating from Odisha, derives its name from the Sanskrit words “patta,” meaning canvas or cloth, and “chitra,” signifying picture. This traditional art form intricately blends classical and folk elements, with a notable inclination toward the folk aesthetic. The term “Pattachitra” encapsulates the essence of this art, involving the creation of vibrant and detailed images on a canvas or cloth surface. These paintings not only showcase the artistic finesse of Odisha but also reflect a harmonious synthesis of classical and folk influences, making Pattachitra a culturally rich and visually captivating tradition. The foundation of Pattachitra paintings lies in treated cloth, and the colors are sourced from natural elements like burnt coconut shells, hingula, ramaraja, and lamp black. Instead of pencil or charcoal, a brush is used to outline figures in red or yellow before filling them with colors. The background is adorned with foliage and flowers, and the paintings boast intricately worked frames. Following the final drawing of lines, a coat of lacquer is applied to impart a glossy finish. The themes of Pattachitra paintings find inspiration in the Jagannath and Vaishnava cults, occasionally incorporating elements from Shakti and Shaiva cults. Raghurajpur in Odisha is celebrated for this art form, with Pattachitra paintings depicting images reminiscent of the old murals in the state, particularly those in Puri and Konark. When executed on palm leaves, this art form is referred to as talapattachitra. |

- Patua Art, originating from Bengal, has a rich history dating back around a thousand years. It began as a village tradition where painters narrated Mangal Kavyas or auspicious stories of Hindu Gods and Goddesses. These paintings, crafted on pats or scrolls, have been passed down through generations, with scroll painters or patuas traveling to various villages to sing their stories. Interestingly, many Patuas are Muslims.

-

- Traditionally executed on cloth, these paintings conveyed religious narratives. In contemporary times, poster paints are applied to sheets of paper sewn together, enabling commentary on political and social issues. The majority of Patuas predominantly come from regions such as Medinipur, Murshidabad, North and South 24 Parganas, and Birbhum districts.

Paitkar Painting

- An ancient art form practiced by the tribal people of Jharkhand, represents one of the oldest schools of painting in the country. This traditional style of painting holds cultural significance with Ma Mansa, a revered goddess in tribal households.

- Paitkar paintings are intricately connected to social and religious customs, including the practices of giving alms and holding yajnas. The predominant theme in Paitkar paintings revolves around the inquiry into ‘What happens to human life post death.’ Despite its historical roots, this art form is facing the threat of extinction, with a notable decline in its practice.

Kalamkari Paintings

- It derive their name from “kalam,” meaning a pen, which is the tool employed to create these exquisite artworks. The pen, typically made of sharp-pointed bamboo, serves to regulate the flow of colors. The canvas for these paintings is cotton fabric, and the colors utilized are derived from vegetable dyes. The process involves soaking the pen in a mixture of fermented jaggery and water, followed by the sequential application of colors onto the canvas.

- The central hubs for Kalamkari painting are Srikalahasti and Machilipatnam in the state of Andhra Pradesh. The artists create freehand images inspired by Hindu mythology. These regions are also recognized for producing textiles with intricate handwork. Notably, Kalamkari painting has a historical lineage dating back to the Vijayanagara empire and has been granted Geographical Indication (GI) status.

Warli Painting

- It takes its name from the Warlis, the indigenous people who have preserved this painting tradition dating back to 2500-3000 BC. The Warlis predominantly inhabit the Gujarat-Maharashtra border. These paintings exhibit a striking resemblance to the mural paintings of Bhimbetka in Madhya Pradesh.

- Characterized by ritualistic themes, Warli paintings typically feature a central motif of a “chaukat” or “chauk,” surrounded by scenes depicting fishing, hunting, farming, dances, animals, trees, and festivals. Among the depicted deities, Palaghata (goddess of fertility) is represented, and male spirits taking human form are also featured.

- Traditionally executed on walls, Warli paintings utilize a basic graphic vocabulary that includes triangles, circles, and squares. Human or animal figures are represented by joining two triangles at the tip, with circles serving as their heads. The base consists of a mixture of mud, branches, and cow dung, giving it a red ochre color. White pigment, made from a combination of gum and rice powder, is exclusively used for painting.

- Initially crafted on walls for auspicious occasions such as harvests and weddings, the popularity of Warli painting has led to adaptations on cloth, with a base of red or black background using white poster color.

Thangka Painting,

- It is originating from Sikkim, Himachal Pradesh, Ladakh region, and Arunachal Pradesh, was initially employed as a medium of reverence, embodying the highest ideals of Buddhism. Traditionally crafted by Buddhist monks and specific ethnic groups, the skill of creating Thangka paintings has been passed down from one generation to another.

- Thangkas are painted on a base of cotton canvas with a white background, utilizing paints made from natural vegetable dyes or mineral dyes. Each color used in the paintings carries its own significance. For instance, red symbolizes the intensity of passion, whether it be love or hatred; golden represents life or birth; white signifies serenity; black depicts anger; green represents consciousness, and yellow conveys compassion. Once the painting is completed, it is often framed in colorful silk brocade.

Manjusha Painting,

- It is originating from the Bhagalpur region of Bihar, is also known as Angika art, with ‘ang’ referring to one of the Mahajan Pada. Due to the prevalent use of snake motifs, it is commonly referred to as snake painting. These artworks are typically created on jute boxes and paper.

Phad Painting,

- It is a distinctive scroll-type art primarily found in Rajasthan with a religious theme, featuring drawings of local deities such as Pabuji and Devnarayan. These paintings, executed with vegetable colors on a lengthy piece of cloth known as “phad,” can range from 15 to 30 feet in length. The subjects are characterized by large eyes and round faces, depicting pompous and joyful narratives. Scenes of processions are commonly portrayed.

Cheriyal Scroll Paintings,

- It is indigenous to Telangana, belong to the Nakashi art tradition. These scrolls unfold as continuous stories, resembling comics or ballads, presented by the Balladeer community. The prevalent themes revolve around Hindu Epics and Puranic stories. These scroll paintings are often substantial in size, reaching up to 45 feet in height. Cheriyal Scroll Paintings were granted Geographical Indication status in 2007.

Pithora Paintings

- They are created by certain tribal communities in Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh, serving religious and spiritual purposes. Executed on the walls of houses, these paintings are believed to bring peace and prosperity. Ritualistically drawn on special family occasions, they commonly depict animals, especially horses.

Saura Paintings,

- It is from Odisha are created by the Saura Tribe and bear similarities to Warli paintings. Primarily wall mural paintings, they hold ritualistic significance and are dedicated to Idital, the main deity of the Sauras. These paintings predominantly use white colors, with a red or yellow backdrop. The colors are sourced from minerals and plants, and the depiction of human shapes follows a geometrical and stick-like style.

- Recently, Saura-style designs have gained popularity, being featured on various items like T-shirts and female clothing.

UPSC PREVIOUS YEAR QUESTIONS

1. The well-known painting “Bani Thani” belongs to the (2018)

(a) Bundi school

(b) Jaipur school

(c) Kangra school

(d) Kishangarh school

2. The painting of Bodhisattva Padmapani is one of the most famous for illustrated paintings at: (2017)

(a) Ajanta

(b) Badami

(c) Bagh

(d) Ellora

3. Kalamkari painting refers to: (2015)

(a) A hand-painted cotton textile in South India

(b) A handmade drawing on bamboo handicrafts in NorthEast India

(c) A block-painted woollen cloth in the Western Himalayan region of India

(d) A hand-painted decorative silk cloth in North-Western India

4. Consider the following historical places: (2013)

1. Ajanta Caves

2. Lepakshi Temple

3. Sanchi Stupa

5. Which of the above places is/are also known for mural paintings?

(a) 1 only

(b) 1 and 2 only

(c) 1, 2 and 3

(d) None

6. Highlight the Central Asian and Greco – Bactrian elements in Gandhara art. (2019)