I-T SEARCHES, A FORM OF EXTRA-CONSTITUTIONAL POWER

Syllabus

- GS2: Government Policies and Interventions for Development in various sectors and Issues arising out of their Design and Implementation.

Why in the News?

- Recently, the Gujarat High Court questioned income-tax authorities regarding a raid on a lawyer, highlighting the prolonged detention of individuals during searches.

- This raises concerns about the unchecked power granted by Section 132 of the Income-Tax Act, seemingly in breach of the proportionality principle established in the Puttaswamy case.

Source: rediff.com

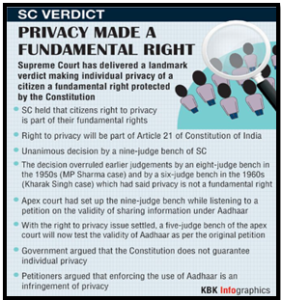

Landmark Verdict: Right to Privacy Affirmed

- In the historic case of Justice K.S. Puttaswamy vs Union of India (August 2017) the Supreme Court of India unequivocally declared the fundamental right to privacy under the Constitution.

- This landmark decision marked a significant shift, emphasizing individual rights as the cornerstone of constitutional discourse.

- The unanimous voice of the 9 judge Bench underscored the centrality of privacy, subjecting any government action infringing upon it to rigorous scrutiny.

- The verdict was anticipated to reshape civil rights jurisprudence, providing a robust shield against arbitrary state intrusions and safeguarding cherished liberties in the modern era.

Courts and Government Power

- Despite the celebrated verdict breathing life into our Constitution, the way laws are understood hasn’t changed much.

- The expected focus on fairness and proportionality is rare.

- Instead, there’s a habit of courts letting the government have a lot of power without much questioning.

- It’s like the courts often trust the government to do what it thinks is right, without demanding strong reasons or fairness.

Source: Business Standards

Taxman’s Extensive Powers

- Section 132 of the Income Tax Act, 1961, gives tax authorities robust authority to forcefully search individuals and properties, confiscating money, precious metals, and valuables.

- This authority depends on authorities having a “reason to believe” that someone has inaccurately reported their income.

- However, concerns arise as the legal foundation for such searches lacks substantial safeguards, potentially leaving individuals vulnerable to invasive actions with limited legal protection.

Tax Raid Controversy

- The Gujarat High Court recently questioned income-tax authorities about a lawyer’s extended raid, where he claims his family was virtually detained for days.

- Such prolonged actions under the Income-Tax Act are not rare.

- Even without a prior judicial warrant, when challenged in court, searches often get approval, showing the judiciary often defers to executive decisions.

- This raises concerns about the balance of power and the need for clearer safeguards to protect citizens during such tax-related operations.

Evolution of Tax Law

- Originally, India’s income-tax law, created in 1922 during colonial times, lacked the power to search and seize.

- It only granted authorities similar powers to civil courts.

- In 1947, the government tried to change this with the Taxation on Income (Investigation Commission) Act.

- However, the Supreme Court, in the case of Suraj Mall Mohta vs A.V. Visvanatha Sastri (1954), rejected

- The Court argued that the law treated certain taxpayers differently, violating the equal treatment guarantee in Article 14 of the Constitution.

Search and Seizure Powers

- In 1961, a new income-tax law introduced Section 132, giving authorities explicit search and seizure powers.

- Challenges arose in Pooran Mal vs Director of Inspection (1973).

- The Supreme Court, referring to its earlier decision in P. Sharma vs Satish Chandra, emphasized the overriding state power for social security.

- The Court argued that since the Constitution didn’t explicitly protect privacy in searches, it couldn’t be added through strained interpretation.

- Also, it rejected the idea that statutory provisions for searches could override constitutional safeguards under Article 20(3).

- This stance reflected the Court’s view on the broad powers granted for social security protection.

Evolution of Legal Interpretation

- In the passage, two key points emerge.

- First, in M.P. Sharma, the concern was criminal procedure searches under magistrate authority, unlike Income-Tax Act searches not needing judicial approval.

- Secondly, the legal landscape shifted. M.P. Sharma was overturned, recognizing evolving interpretive tools.

- Puttaswamy emphasized interconnected constitutional rights, rejecting isolated silos.

- Notably, evolving judicial perspectives acknowledged that the right to privacy is integral to personal liberty (Article 21).

- The court recognizes this shift, embracing tools to uphold broader rights.

- This evolution reflects a contemporary understanding that constitutional guarantees work together rather than in separate compartments.

Legal Safeguards in Searches

- According to the Puttaswamy judgment, state powers to search and seize are not just about social security but are governed by the proportionality doctrine.

- This means the use of these powers must have a valid purpose, be logically connected to that purpose, have no less intrusive alternatives, and strike a fair balance between the government’s goal and the individual’s rights.

- In simpler terms, searches must be justified, reasonable, and not overly invasive, respecting citizens’ rights.

Neglecting Privacy in Tax Searches

- Section 132 of the Income-Tax Act, as observed, seems to disregard the proportionality principle established by Puttaswamy.

- In a recent case, the Court, in Principal Director of Income Tax vs Laljibhai Mandalia, overlooked Puttaswamy’s guidance.

- It deemed the opinion formation for a search as administrative, not judicial, downplaying privacy concerns.

- This raises questions about the adequacy of legal safeguards in tax searches, potentially compromising individual rights in the process.

Wednesbury Principle in Tax Searches

- The Court, in Principal Director of Income Tax vs Laljibhai Mandalia, advocated the “Wednesbury” principle for tax searches.

- This principle assesses the honesty and bona fide nature of the belief behind a search, not its sufficiency.

- Originating from a 1948 UK case, it questions whether a decision is so outrageous that no reasonable person could arrive at it.

- While seemingly straightforward, its application could risk overlooking nuanced privacy concerns and the need for robust legal scrutiny in tax search operations.

Post-Puttaswamy: Challenging the Wednesbury Rule

- Following the Puttaswamy judgment, the Wednesbury rule finds no place, especially when fundamental rights are concerned.

- Our constitutional principles demand strict adherence to statutory law in executive actions.

- Warrants for income-tax searches must reflect careful consideration and withstand rigorous judicial scrutiny.

- Any other interpretation could grant the executive undue, extra-constitutional power, posing a risk of significant public harm.

| Wednesbury Principle in Tax Searches

· The Wednesbury Principle is a crucial tool in judicial review of tax searches under Section 132 of the Income-Tax Act, 1961. · It assesses the reasonableness of Income-Tax authorities’ actions based on three criteria Criteria · Irrationality: Judges scrutinize if the search decision has a logical basis and justification in the available information. · Perversity: The decision is evaluated for being so unreasonable that it appears arbitrary, deviating from established norms. · Extraneous Factors: Judges check if the decision was influenced by irrelevant considerations beyond the Income-Tax Act’s scope. |

Source

Mains Practice Question

Discuss the implications of Section 132 of the Income Tax Act in light of the fundamental right to privacy established by the Supreme Court in the Puttaswamy case. Examine how the provision grants unrestricted police power to tax authorities and the challenges it poses to individual liberties.

Source: rediff.com

Source: rediff.com Source: Business Standards

Source: Business Standards