Climate Finance- A Hard Fact Amidst Shifting Commitments.

Relevance

- GS Paper 3.

- Conservation, environmental pollution and degradation, environmental impact assessment.

- Tags: #climatefinance #climatechange #india #currentaffairs #upsc

Why in the News?

A new report by the New Delhi-based think tank Centre for Science and Environment says Climate finance is not going to the countries where it is needed the most.

The G20 Presidency and Climate Change Polarization

- As India assumes the G20 presidency, global consensus-building faces challenges, particularly in the realm of climate change. Among the contentious issues, climate finance stands out, with the present commitments by developed nations falling significantly short.

- The promise of $100 billion for projects in developing countries, formulated about a decade and a half ago, lacks a solid foundation and rational basis. While the figure was inadequate even when it was first estimated, the ongoing debate centers on the developed world’s failure to deliver this modest sum of $100 billion annually to support developing nations.

Discrepancies in Commitments: Fossil Fuel Subsidies vs. Climate Finance

- Ironically, a revealing contrast emerges when comparing climate finance commitments to fossil fuel subsidies. Over the years spanning from 2011 to 2020, fossil fuel subsidies in 51 countries outstripped climate finance expenditures by a staggering 40% (Climate Policy Initiative).

- While the developed world (OECD) contends that it provided nearly $80 billion for climate finance in 2020, skeptics assert that actual resource transfers would only amount to a range of $19-22 billion.

- The developed world’s claims often include commercial debt for climate-related ventures in their calculations, illustrating a strategic ambiguity. This tactic overlooks the primary intention of the promised $100 billion, meant to be concessional finance or grants.

The Imposing Need and the Current Reality: Climate Finance Discrepancy

- Considering that the need for climate finance is estimated at around $4.35 trillion to meet Paris Agreement targets, the reality starkly contrasts with actual expenditures, which represent only a seventh of this amount.

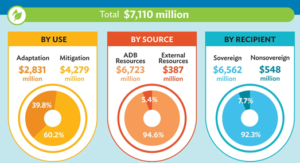

- Climate finance is typically divided into two categories: mitigation and adaptation. While mitigation involves establishing renewable generation projects, adaptation encompasses initiatives like constructing sea walls to prevent flooding.

- A significant majority of climate finance currently flows towards mitigation efforts (93%), emphasizing their commercial viability. This underlines the pressing need for alternative approaches.

Necessity for New Approaches: Mobilizing Resources for Climate Finance

- Given the inadequate commitments and the dire need for climate finance, countries, India included, must turn inward to mobilize resources. Collaborative efforts among various institutions are essential, combining their strengths to address the challenge.

- Financial institutions play a key role in supporting commercially mature technologies such as wind, solar, and electric mobility. However, the high costs associated with adaptation projects with extended timelines deter conventional financial support.

Challenges in Adaptation: Government Involvement and Private Sector

- Adaptation projects present unique challenges. They demand substantial upfront costs, possess extended gestation periods, and lack defined income streams. Consequently, they are perceived as high-risk investments by financial institutions.

- Private sector involvement is crucial for adaptation initiatives, necessitating government intervention.

- Yet, private sector participation in adaptation projects remains meager, accounting for less than 2%.

- The hesitancy stems from the risk perception and uncertainties surrounding adaptation’s scope.

Stagnation in Commitments: The Unresolved $100 Billion Debate

- The prolonged debate over the $100 billion commitment underscores a fundamental truth: this promised amount is unlikely to materialize.

- The establishment of a loss and damage fund, discussed at CoP27, may address immediate concerns like rising sea levels and desertification, but details remain elusive.

- The proposed fund’s quantum and implementation timeline remain undecided, further delaying tangible actions.

Future Prospects: Redefining Strategies for Climate Finance

- For nations like India, self-reliance and innovation are the paths forward. A $100 billion annual commitment pales in comparison to the actual financial requirements.

- Countries must embrace alternative methods to bolster climate finance, including imposing carbon taxes, issuing green bonds, and exploring catastrophe bonds.

- While the $100 billion goal seems distant, countries can no longer wait; they must take proactive steps to secure their environmental future.

With climate finance commitments falling short, countries, especially India, must recognize the inadequacy of the $100 billion promise. Turning inwards and pooling resources across institutions are crucial steps. As the global climate crisis deepens, nations can’t rely solely on pledges but must embark on innovative paths to secure the financial backing required to tackle climate change.

Climate Finance: Key Points

- Definition Dilemma: Climate finance lacks a global definition but broadly refers to funding at various levels to combat climate change, focusing on emissions mitigation, greenhouse gas sinks, and vulnerability reduction.

- $100 Billion Goal: Originating in 2009 and reinforced by the Paris Agreement, developed nations pledged $100 billion annually by 2020 to aid developing countries in climate challenges.

- Paris Agreement Article 9: Developed countries are obligated under Article 9 to offer financial support to help developing nations tackle climate change issues.

- Inadequate Commitment: The $100 billion commitment, although not negotiated, falls short of the actual climate-related requirements of developing nations.

- Projected Finance Needs: Reports suggest the need for external climate finance ranges from $1 trillion to $11.5 trillion annually by 2030.

- Current Funding Status: In 2020, only $83.3 billion of the promised $100 billion was allocated to developing economies, primarily in loans rather than grants.

- Global Environment Facility (GEF): Established in 1992, GEF offers grants for projects related to biodiversity, climate change, and more, supported by 18 agencies.

- Green Climate Fund (GCF): Created in 2010, GCF aims to promote collective action against climate change and operates as part of the financial mechanism, guided by COP.

- Other Special Funds Special Climate Change Fund (SCCF) and Least Developed Countries Fund (LDCF) managed by GEF, along with the Adaptation Fund (AF) established in 2001.

- Collective Action Needed: Climate finance remains essential in tackling climate change. While $100 billion is a step forward, the situation requires broader and more ambitious efforts. Funds like GEF and GCF play a critical role in directing financial resources where needed.

- Urgency in Action: As the climate crisis escalates, collective action and increased financial support are crucial for a sustainable future.

https://www.adb.org/news/infographics/climate-finance-2022

https://epaper.indianexpress.com/3755390/Delhi/August-30-2023#page/1/1

Mains Question

Analyzing the inadequacy of climate finance commitments, the challenges of adaptation, and the discrepancies in global efforts, discuss the potential strategies that countries like India could adopt. 250words