The anatomy of the Yamuna floodplains

Current Context:

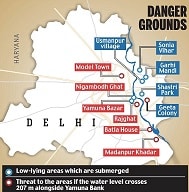

- The water level of the Yamuna in Delhi breached the danger mark again on Sunday following a surge in discharge from the Hathnikund Barrage into the river after heavy rain in parts of Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh.

- Further increase in the water level of the river is expected to impact relief and rehabilitation work in the flood-affected low-lying areas of the capital, officials said.

- Battered by heavy rains, the Yamuna looks slow, sluggish and swollen. Last week, the water levels hit a 60-year-high, gushing through elite neighborhoods built close to the floodplains. Waters advanced towards the Taj Mahal for the first time in half a century.

Why is the Yamuna important?

- The late environmentalist Anupam Mishra once called Yamuna, Delhi’s “real town planner”: it meandered through Delhi ensuring the city was never short of water and never ravaged by famine or flood.

- Delhi was “well-planned along the course of the river Yamuna, but it isn’t so anymore. Causes, can be traced to haphazard construction activities, rapid urbanization, lack of proper housing and lax regulations — all of which have besieged the floodplains.

- We talk about rivers in isolation, but floodplains are inseparable from the river channel. The river system includes both water and land. Yamuna is a lifeline to five States, and its floodplains are a charging point.

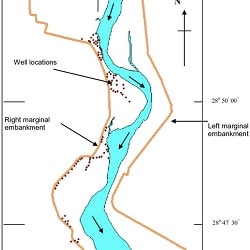

- Yamuna courses east of Delhi, entering the city from Palla village and exiting at the Okhla barrage.

- The floodplains are two km wide on each side. The floodplain along Yamuna’s 22 km run in Delhi, designated as the O zone by the Delhi Development Authority, has an area of approximately 9,700 hectares — the size of 1,500 new Parliament buildings.

- Between Palla and Okhla, the composition of the floodplains changes from farmlands to slums, colonies, flyovers and bridges. It is also dotted with permanent structures like Ring Road, Akshardham Temple complex, Commonwealth Games Village, Player’s Building (housing the Delhi Secretariat) and the Indira Gandhi Indoor Stadium.

- A river has the “right to expand” and needs to breathe through its flood plains. Any attempt to concretize constricts its air supply. “This is happening not only in Delhi, but all major cities including Pune, Lucknow, Mumbai,”.

- As part of river systems, floodplains slow water runoff during floods, recharge groundwater and store excess water, replenishing the city’s water supply. When you have sluggish flow, the surplus water stored in the floodplain is released back during the non-monsoon season.

- If you lose the floodplain, you also lose the storage of water.” Delhi recorded similarly devastating floods in 1978, 1988 and 1995 which inundated floodplains, adversely impacting their health.

Who lives on these floodplains?

- A 2022 report found there are 56 bastis (one basti has 15 or more houses), with 9,350 households and 46,750 people. Almost half of the households (4,835) practice farming as a livelihood; others rely on daily wage work, fishing, nurseries, and animal herding.

- Most residents migrated from Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Haryana, Jharkhand, West Bengal and Rajasthan; some bastis have existed for eight decades and others were built more recently.

- Farmers near Palla and Hiranki villages traditionally grow rice, wheat, and flowers on the rich silt deposited by the river.

- “Zone O supports a large variety of nature-based livelihoods with a low ecological footprint.

- Yet, these are being forcibly evicted in the name of ecological rejuvenation of the region,” the report noted. The farmland size has reduced from 4,850 hectares in 2000 to 3,330 hectares in 2020, as people were evicted, and livelihood shifted to daily wage work.

- The National Green Tribunal (NGT) in 2016 imposed a blanket ban on agriculture-related activities till the “Yamuna is restored and made pollution free”.

- On the NGT’s orders, the DDA in 2021 evicted 800 families in the Muslim-dominated Batla House area, a part of the floodplains that falls under no-construction zones. Private contractors built flats and sold to people, mostly daily wage and domestic workers, who cannot afford housing in other areas.

How did settlements emerge?

- The first major non-agriculture settlements appeared after Independence when refugees from Western Punjab fled to Delhi.

- They built kuccha houses on the floodplains along the Yamuna Pushta (from the ITO bridge and up to Salimgarh Fort).

- The planning era propelled urbanization in the 1950s and ‘60s, witnessing the construction of the first thermal power plant (employing people as laborers to unload coal from trains and clear fly ash), the Ring Road and Rajghat Samadhi.

- Over 180,000 jhuggis on the Yamuna Pushta were demolished during the 1975 Emergency, and people were resettled in the peripheries.

- The 1982 Asian Games brought more than one million migrant laborers from neighboring States, tasked with building flyovers, sports facilities and luxury apartments. Little to no formal housing was provided; workers eventually settled on the open plain along the western embankment after the Games.

- By 2004, almost 3,50,000 people lived along the Yamuna, according to estimates.

- They earned livelihoods as domestic help, rickshaw pullers, porters, mechanics, small vendors, factory workers in nearby trade markets such as Chandni Chowk and Sadar Bazaar.

- The population boom outpaced Delhi’s ability to build a proper sewage network and spiked Yamuna’s pollution, Manu Bhatnagar of the Natural Heritage Division of Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage told The Hindu in an earlier interview.

Delhi HC Verdict: The Delhi High Court in 2004 ordered eviction of “unauthorized” settlements on the floodplains, demolishing shanties and evicting more than two lakh people.

What does Delhi’s Master Plan outline?

- The Yamuna floodplain was designated as a protected area free from construction in the Delhi Masterplan of 1962. The Central Ground Water Authority in 2000 also notified the floodplains as ‘protected’ for groundwater management.

- The draft Master Plan For Delhi 2041 divides Delhi into 18 zonal areas, designating Yamuna’s floodplains as ‘Zone O’, delineated in two parts: river zone (active floodplain) and riverfront (regulated construction is allowed). The latter is where structures such as Akshardham Temple and Commonwealth Village have been built.

- The South Asia Network on Dams, Rivers and People (SANDRP) in 2020 found large parts of the Yamuna floodplains and riverbed were “grossly abused” due to lax implementation: 23 bridges including rail, road, metro and barrages have been built; there was a bridge at every 800m.

- “The creation of new embankments, guide bunds are fragmenting the floodplain, promoting encroachments, and also leaving a trail of construction and demolition debris into riverbed and floodplains,” the group wrote.

- An Expert Committee in 2012 formed to examine DDA’s Riverfront Development Scheme warned against any construction on floodplains. The areas proposed under the Yamuna Riverfront Development (YRDF) plan — which proposes biodiversity parks and ‘recreational’ activities — were within the active floodplain, which could affect the topography, increase pollution and affect flood-carrying capacity, the Committee warned.

- If you build on areas reserved for recharge, you lose groundwater. The layers of sediments of floodplains create aquifers contributing to the river channel, which in turn rejuvenates the groundwater. But encroachments stop this two-way exchange.

- The river is unable to transport flood waters downstream during monsoons, wet the lands or deposit soil along its banks to preserve the riverine ecosystem.

What do encroachments do?

- Floodplains also protect against devastating flash floods by allowing excess water to spread out and storing that surplus.

- However, encroachments restrict the river to a small channel. Any intense rainfall activity (India received 26% more rainfall in July than expected) swells the river, expanding in height not in width, eventually spilling over with devastating intensity.

- Climate change has intensified rains in frequency and severity, and seen in the Yamuna floods, runoff water comes as a huge gushing flow in a small span of time.

- Floods are inseparable from the hydrological cycle and are required for sediment transport, cleaning the riverbed, rejuvenating the river itself.

- “The concept of floodplain zoning is not mainstreamed in the Master Plan,” he adds, and authorities haven’t yet “taken cognizance of the river’s right to expand.”

- This gap, along with poorly implemented policies, frees up river land for private and public real estate. “The common property land — the river’s land — is open to auction and revenue generation. It’s a tragedy of commons because the river’s land has not been properly defined.”

- A model draft Bill for defining floodplains and zoning was circulated in 1975. Only four States have drafted a National Floodplains Zoning Policy so far.

- It is “reductive” to locate floodplains as a site of conflict between development and nature. Instead, action can be focused on creating climate-resilient infrastructures, de-silting drains, creating green areas and improving drainage systems. “You cannot police a river,” he says.