El Niño in the Pacific ocean is of concern to India

Context: Seven years after 2016, El Niño is back in the Pacific Ocean, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) of the United States federal administration, announced.

What is El Niño?

- El Niño, which in Spanish means “little boy”, is a climate pattern that develops along the equatorial Pacific Ocean after intervals of a few years ranging between 2 and 7 years.

- Essentially, water on the surface of the ocean sees an unusual warming in a band straddling the equator in the central and east-central pacific — broadly extending from the International Date line and 120°W longitude, i.e., off the Pacific coast of South America, west of the Galapagos islands.

How and why does El Niño happen?

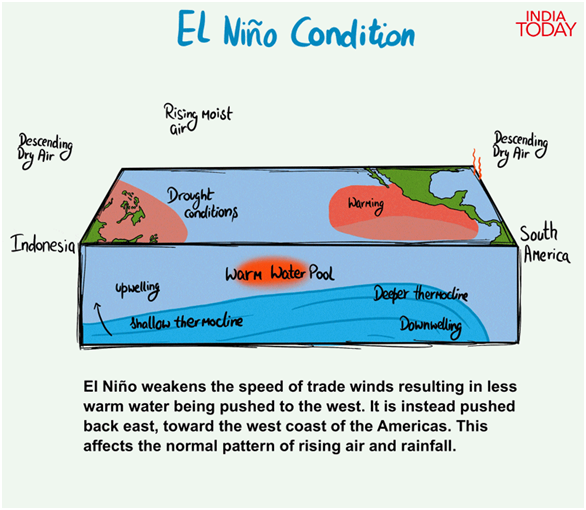

- When the so-called El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is in its neutral phase, the trade winds blow west along the equator and take the warm water from South America towards Asia. However, during an event of El Niño, these trade winds weaken (or may even reverse) — and instead of blowing from the east (South America) to the west (Indonesia), they could turn into westerlies

- In this situation, as the winds blow from the west to east, they cause masses of warm water to move into the central and eastern equatorial Pacific Ocean, and reach the coast of western America.

- During such years, there prevails warmer-than-average sea surface temperatures along the equatorial Pacific Ocean.

What is the impact of El Niño conditions?

- Globally, El Niño has been associated with severe heatwaves, floods, and droughts in the past.

- “Depending on its strength, El Niño can cause a range of impacts such as increasing the risk of heavy rainfall and droughts in certain locations around the world.

How severe are this year’s El Niño conditions?

- The 2023 event is the fifth since 2000 — which means they develop every 4-5 years on average. At the start of this year, an El Niño was predicted to emerge by August, which would have meant it would coincide with the second half of the June-September southwest monsoon season in India.

- This, however, did not happen as predicted. Sea surface temperatures along the equatorial Pacific Ocean, especially along the various Niño regions, have been showing signs of much more rapid warming than had been predicted by the weather models.

- The Niño 3.4 index value — the vital indicator confirming an event of El Niño — jumped from minus 0.2 degrees Celsius to 0.8 degrees Celsius between March and June this year. Whereas, the threshold value of this index is 0.5 degrees Celsius.

- Meteorologists have noted that such accelerated rates of warming, following three years of La Niña (the opposite phase of ENSO) that ended in February this year, was unusual.

How worried should India be about this development?

- In the Indian context, over the last hundred years, there have been 18 drought years. Of these, 13 years were associated with El Niño. Thus, there seems to be a correlation between an El Niño event and a year of poor rainfall in India.

- Also, between 1900 and 1950, there were 7 El Niño years but during the 1951-2021 period, there were 15 El Niño years ( 2015, 2009, 2004, 2002, 1997, 1991, 1987, 1982, 1972, 1969, 1965, 1963, 1957, 1953 and 1951). This suggests that the frequency of El Niño events has been increasing over time.

- Of the 15 El Niño years in the 1951-2021 period, nine summer monsoon seasons over the country recorded deficient rain by more than 90 per cent of the Long Period Average (LPA).

- “Climate change can exacerbate or mitigate certain impacts related to El Niño. It could lead to new records for temperatures, particularly in areas that already experience above-average temperatures.

| Practice Question

1. Explain the impact of El-Nino on the social and economic context of India? |