HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Introduction

The British initially arrived in India as traders in 1600 through the East India Company. By 1765, the Company had acquired revenue and civil justice rights in parts of India, transforming it into a territorial power. In 1858, after the “sepoy mutiny,” British Crown rule replaced Company rule in India. India gained independence on August 15.

1947, leading to the formation of a Constituent Assembly that drafted the Indian Constitution, which came into effect on January 26, 1950. The British colonial period greatly influenced India’s political and constitutional systems, with many features of the Indian Constitution and governance structure having their origins in this historical period.

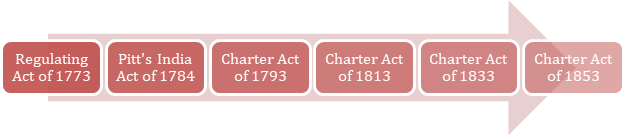

The Company Rule (1773–1858)

Regulating Act of 1773

- The Regulating Act of 1773 was a significant piece of legislation passed by the Parliament of Great Britain to regulate and reform the administration of British territories in India, particularly those under the control of the East India Company. Here are some key points about the Regulating Act of 1773:

- Background: Prior to the Regulating Act, the East India Company had established itself as a dominant power in India, with its own military and administrative apparatus. However, there were growing concerns about the mismanagement of Company affairs and the need for oversight.

- Key Provisions:

- Governor of Bengal: The Act created the position of Governor-General of Bengal, who was to be the highest-ranking official in British India. The first person to hold this position was Warren Hastings.

- Supervision: The Governor-General was given powers to supervise and control the other Presidencies of Madras and Bombay. This centralized authority aimed to bring better coordination and oversight.

- Council: A council of four members was established to assist the Governor-General. This council was to advise and participate in decision-making.

- War and Peace: The Governor-General had the authority to declare war or make peace with Indian states. This was a significant departure from previous practices.

- Financial Control: The Act attempted to bring some financial control by requiring the Governor-General and his council to send detailed reports and budgets to London. This aimed to prevent financial abuses.

- Judicial Reforms: The Act also made provisions for some judicial reforms, including the establishment of a Supreme Court in Calcutta (now Kolkata).

- Impact: While the Regulating Act of 1773 was an early attempt to bring regulation and oversight to British India, it had several limitations and was later amended and replaced by subsequent acts. Nevertheless, it marked the beginning of formal British colonial administration in India and laid the groundwork for future legislative acts that further defined the governance structure.

- The Regulating Act of 1773 was a crucial step in the British colonial rule of India and set the stage for further developments in the administration and governance of the Indian subcontinent under British control.

Pitt’s India Act of 1784

- Pitt’s India Act of 1784, formally known as the East India Company Act 1784, was a significant piece of legislation passed by the British Parliament during the tenure of Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger. This act was part of the ongoing efforts by the British government to regulate and reform the administration of the British East India Company, which had established its dominance in India and raised concerns about mismanagement and abuse of power. The key points related to Pitt’s India Act of 1784 are as follows:

- Background: Prior to the passage of this act, the British East India Company exercised significant power in India but had faced criticism and accusations of corruption and misrule. The British government sought to address these issues and bring about better control and oversight.

- Governor-General: The act established the office of the Governor-General of India and defined the Governor-General’s role as the head of British India. The first Governor-General appointed under this act was Warren Hastings.

- Governor-General in Council: The Governor-General was to be assisted by a council, which consisted of three members appointed by the British Crown. This council played a crucial role in decision-making and advising the Governor-General.

- War and Peace: The Governor-General in Council was given the authority to declare war and make peace with Indian states. This centralized authority aimed to provide more consistency in British policy and actions in India.

- Financial Control: The act established a system of double government, meaning that both the British government and the East India Company had financial control. The British government could now regulate and oversee the Company’s financial affairs more closely.

- Oversight: The act empowered the British government to closely monitor and regulate the actions and policies of the East India Company in India. It aimed to bring transparency and accountability to the Company’s operations.

- Judicial Reforms: The act continued the efforts to reform the judicial system in India by establishing new courts and procedures, including the Supreme Court in Calcutta.

- Pitt’s India Act of 1784 marked a significant shift in the governance and oversight of British India. It aimed to address some of the issues and abuses associated with the East India Company’s rule and introduced a system of dual control, with the British government playing a more active role in the governance of India. This act laid the groundwork for future reforms and changes in the administration of British India.

Charter Act of 1793

- The Charter Act of 1793 was an important piece of legislation passed by the British Parliament that had a significant impact on the governance of British India during the colonial period. Some of the key provisions and aspects of the Charter Act of 1793:

- Governance of India: The act continued and extended the provisions of the previous Charter Act of 1784, which established the Governor-General of India and his council as the highest authority in British India.

- Governor-General’s Council: The Governor-General’s Council was expanded to include a fourth member, making it a council of four members. This council was responsible for advising and assisting the Governor-General in making important decisions.

- Commercial Regulations: The Charter Act of 1793 continued to regulate the activities of the British East India Company in India, especially in matters related to trade and commerce.

- Land Revenue: The act provided for the appointment of a Board of Revenue to oversee land revenue collection and administration in the provinces. This was aimed at improving revenue collection and management.

- Governor-General’s Power: The Governor-General was given the authority to act without the concurrence of his council in certain situations, primarily related to external affairs and defense.

- Freedom of the Press: The act introduced a provision that required the Governor-General and his council to allow for the publication and circulation of books and papers without any prior censorship, with the exception of matters related to the British government and its relations with foreign states.

- Amendments and Repeals: The Charter Act of 1793 made several amendments and repeals to earlier acts and regulations, including provisions related to judicial matters and the administration of justice.

- Duration: The act was initially intended to be in force for 20 years, but it could be extended or modified by subsequent acts of Parliament.

- The Charter Act of 1793 represented a continuation of the British government’s efforts to regulate and reform the governance of India under British East India Company rule. It addressed various aspects of administration, including the role and powers of the Governor-General, commercial regulations, revenue collection, and freedom of the press. This act, like its predecessors, played a significant role in shaping the legal and administrative framework of British India during the colonial period.

Charter Act of 1813

- The Charter Act of 1813, officially known as the “Charter Act for the Renewal of the East India Company’s Charter,” was a significant piece of legislation passed by the British Parliament regarding the governance and administration of British India under the control of the East India Company. The major key provisions and aspects of the Charter Act of 1813:

- Renewal of Charter: The act renewed the charter of the British East India Company for a period of 20 years. This charter was periodically renewed by the British government and granted the Company the authority to continue its operations in India.

- Christianity and Education: One of the most notable features of the Charter Act of 1813 was its provisions related to Christianity and education. It allocated a substantial sum of money for the promotion of education and the translation of Christian religious texts into native languages in India.

- Provision for Charity and Public Instruction: The act earmarked a sum of one lakh (100,000) rupees annually for promoting the education of Indians and the spread of European literature and science.

- Regulation of Company’s Trade: The act further regulated the trading activities of the East India Company by restricting its commercial monopoly, particularly in trade with China. It allowed for the participation of private traders in certain areas of commerce.

- Governance and Financial Control: The act maintained the Governor-General of Bengal as the highest authority in India but provided for the appointment of a second member to the Governor-General’s council to assist in financial matters.

- Prohibition of Slavery: The Charter Act of 1813 declared the trafficking of slaves to be illegal within the territories of the East India Company.

- Duration: Similar to earlier charter acts, the Charter Act of 1813 had a 20-year duration but could be extended or modified by subsequent acts of Parliament.

- The Charter Act of 1813 had a significant impact on British India, particularly in the areas of education and the promotion of Christian missionary activities. It marked a shift toward greater British involvement in Indian education and culture. Additionally, it began to loosen the trading monopoly of the East India Company by allowing for some private trade. The act reflected the evolving priorities of the British government in India during the early 19th century and laid the groundwork for further changes in the governance and administration of India under British rule.

Charter Act of 1833

- The Charter Act of 1833, also known as the Saint Helena Act 1833, was a significant piece of legislation passed by the British Parliament regarding the governance and administration of British India under the control of the East India Company. It introduced several important reforms and changes in the way India was governed. Here are the key provisions of the Charter Act of 1833:

- Governance Reforms: The act continued the governance structure established by previous charter acts, with the Governor-General of Bengal being the highest authority in India. However, it allowed for the appointment of a Law Member to the Governor-General’s Council to focus on legal and judicial matters.

- Company’s Trade Monopoly: The East India Company’s trade monopoly was significantly reduced. It allowed private traders to enter into trade with India, except for trade in tea and trade with China.

- Appointment of Indian Civil Servants: The act allowed Indians to be eligible for certain positions in the civil services of the Company. However, it maintained that the highest ranks of the civil service would be reserved for Europeans.

- Power of Legislative Councils: The act granted legislative powers to the Governor-General’s Council and the councils of Madras and Bombay. This marked a significant step toward representative government, although it was limited in scope.

- Publication of Laws: All laws, rules, and regulations passed in India were required to be published, making them more accessible to the public.

- Religious and Social Reform: The act aimed to promote social and religious reforms by providing funds for the promotion of education and the translation of works into native languages.

- End of Company’s Trading Activities: The Charter Act of 1833 ended the East India Company’s commercial activities altogether, except for the trade in tea with China.

- Duration: Similar to earlier charter acts, the Charter Act of 1833 had a 20-year duration but could be extended or modified by subsequent acts of Parliament.

- The Charter Act of 1833 had a profound impact on the governance and administration of India. It marked a significant shift in British policy by reducing the East India Company’s commercial role and introducing important reforms in governance, trade, and representation. It laid the foundation for further changes in the governance structure of British India and played a crucial role in shaping the trajectory of British colonial rule in India.

Charter Act of 1853

- The Charter Act of 1853, officially known as the India Act 1853, was a significant piece of legislation passed by the British Parliament that introduced several important reforms in the governance and administration of British India. The key provisions and aspects of the Charter Act of 1853 are as follows:

- Governance Reforms: The act maintained the existing governance structure, with the Governor-General of India being the highest authority. It continued the practice of appointing a Governor-General, but now this individual could also hold the title of Viceroy of India, signifying the paramount authority in India.

- Legislative Powers: The act expanded the legislative powers of the Governor-General’s Council to allow for the creation of laws and regulations for the whole of India. This represented a significant shift of power from the British Parliament to India.

- Local Representation: The act provided for the nomination of non-official members to the Governor-General’s Council, allowing for a degree of Indian representation. However, the majority of the council remained British officials.

- Local Legislation: The act allowed the provincial legislative councils in Madras and Bombay to make laws and regulations for their respective territories, subject to the approval of the Governor-General’s Council.

- Revenue and Finance: It introduced reforms in revenue and financial administration, including a system for financial reporting and budgeting.

- Indian Civil Service: The act continued to allow Indians to be eligible for certain positions in the civil services of the East India Company, but Europeans were still given preference for the highest ranks.

- Judicial Reforms: The Charter Act of 1853 addressed issues related to the administration of justice, including the appointment of Indian judges in lower courts.

- Freedom of Religion: It reaffirmed the commitment to religious freedom in India and prohibited discrimination based on religious grounds.

- Duration: Like earlier charter acts, the Charter Act of 1853 had a 20-year duration but could be extended or modified by subsequent acts of Parliament.

- The Charter Act of 1853 represented a significant step toward increased governance autonomy for India and introduced some measures aimed at including Indian representation in legislative bodies. While it fell short of providing full self-governance, it marked a move away from direct rule from Britain and set the stage for further constitutional reforms in India during the later 19th and early 20th centuries.

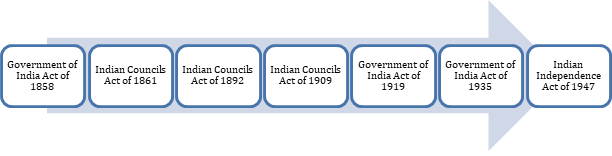

THE CROWN RULE: 1858-1947

Government of India Act of 1858

- The Government of India Act of 1858, also known as the Act for the Better Government of India, was a significant piece of legislation passed by the British Parliament in the aftermath of the Indian Rebellion of 1857 (often referred to as the Sepoy Mutiny or the Indian Uprising). This act brought about major changes in the governance and administration of India, effectively ending the rule of the British East India Company and transferring control of India to the British Crown. The key provisions and aspects of the Government of India Act of 1858:

- End of Company Rule: The act ended the rule of the British East India Company in India. The Company’s powers and privileges were revoked, and its territories were transferred to the British Crown.

- Authority of the British Crown: The act established that India was to be governed directly by the British Crown, and the Queen’s government (the British government) would have direct control over Indian affairs.

- Secretary of State for India: The act created the position of Secretary of State for India within the British Cabinet. This Secretary of State was responsible for overseeing India’s governance and administration and was accountable to the British Parliament.

- Governor-General and Viceroy: The Governor-General of India was now designated as the Viceroy of India, signifying the highest authority in India under the British Crown.

- Indian Councils: The act expanded the Governor-General’s Executive Council to include more members, both British and Indian. However, the majority of members remained British officials.

- Legislative Councils: Legislative councils were established in India, allowing for the creation of laws and regulations for India by elected and appointed members. This marked a significant move toward representative government.

- Local Governance: The act introduced provisions for local governance through municipalities and local boards.

- Judicial Reforms: Judicial reforms included the establishment of high courts and the appointment of Indian judges to these courts.

- Indian Civil Service: The act continued to allow Indians to be eligible for certain positions in the civil services of the British Crown, but Europeans were still given preference for the highest ranks.

- Religious Freedom: The act reaffirmed the commitment to religious freedom in India and prohibited discrimination based on religious grounds.

- Financial Control: Financial control was vested in the Secretary of State for India, and the act introduced financial reporting and budgeting systems.

- Duration: The Government of India Act of 1858 did not have a fixed duration and remained in force until it was significantly amended by subsequent legislation.

- The Government of India Act of 1858 marked a pivotal moment in Indian history as it ended the rule of the British East India Company and transferred control of India to the British Crown. It initiated a new era in Indian governance under direct British control, introduced some representative elements, and laid the groundwork for future constitutional reforms in India during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Indian Councils Act of 1861

- The Indian Councils Act of 1861, was an important piece of legislation passed by the British Parliament that introduced significant changes to the legislative and administrative structure of British India. The key provisions and aspects of the Indian Councils Act of 1861:

- Beginning of Representative Institutions: The Act marked the beginning of representative institutions in British India by involving Indians in the legislative process. It allowed the Viceroy to nominate some Indians as non-official members of his expanded council. For example, in 1862, under this provision, Lord Canning, the Viceroy at the time, nominated three Indians to his legislative council, including the Raja of Benaras, the Maharaja of Patiala, and Sir Dinkar Rao.

- Decentralization of Legislative Powers: The Act initiated the process of decentralization by restoring legislative powers to the Bombay and Madras Presidencies. This reversal of the centralizing tendency that had started with the Regulating Act of 1773 reached its peak under the Charter Act of 1833. This policy of legislative devolution ultimately led to the grant of almost complete internal autonomy to the provinces in 1937.

- Establishment of New Legislative Councils: The Act provided for the establishment of new legislative councils for specific regions, including Bengal, the North-Western Provinces, and Punjab. These councils were set up in 1862, 1886, and 1897, respectively.

- Portfolio System: The Act recognized and formalized the ‘portfolio’ system, which was introduced by Lord Canning in 1859. Under this system, a member of the Viceroy’s council was made in charge of one or more government departments and was authorized to issue final orders on behalf of the council for matters within their department(s).

- Emergency Ordinances: The Act empowered the Viceroy to issue ordinances during emergencies without the concurrence of the legislative council. These ordinances had a limited life of six months.

- Overall, the Indian Councils Act of 1892 represented a significant step toward greater Indian participation in the legislative process, the decentralization of legislative powers, and the establishment of representative institutions at the regional level. These reforms played a role in shaping the evolution of governance in British India in the years to come.

Indian Councils Act of 1892

- Increase in Non-Official Members: The Act increased the number of non-official members in both the Central and provincial legislative councils. However, it maintained the official majority in these councils. In other words, while there was an expansion in non-official representation, the government officials still held the majority of seats.

- Enhanced Functions of Legislative Councils: The Act granted additional powers and functions to the legislative councils. It allowed them to discuss the budget and address questions to the executive, giving them a more significant role in the governance process.

- Nomination of Non-Official Members: The Act provided for the nomination of some non-official members in both the Central Legislative Council and provincial legislative councils. These nominations were made on the recommendation of various bodies, including provincial legislative councils, the Bengal Chamber of Commerce, district boards, municipalities, universities, trade associations, zamin-dars (landowners), and chambers.

- Introduction of Limited Election Process: The Act introduced a limited and indirect provision for filling some non-official seats in both the Central and provincial legislative councils. While the term “election” was not used in the Act, the process was described as nominations made on the recommendation of specific bodies.

- These provisions of the Indian Councils Act of 1892 aimed to increase Indian representation in legislative councils and enhance their functions. However, it’s important to note that the government officials still held a majority in these councils, and the reforms did not grant full legislative powers to these bodies. The Act marked a step towards greater Indian participation in the legislative process but fell short of achieving full representative government.

Indian Councils Act of 1909

- The Indian Councils Act of 1909, also known as the Morley-Minto Reforms of 1909, was an important piece of legislation passed by the British Parliament that introduced significant changes to the legislative and administrative structure of British India. It was named after the Secretary of State for India, John Morley, and the Viceroy of India, Lord Minto, who were involved in its formulation. Major provisions and aspects of the Indian Councils Act of 1909:

- Expansion of Legislative Councils: The Act significantly increased the size of both the Central and provincial legislative councils. The number of members in the Central legislative council was raised from 16 to 60, while the number of members in provincial legislative councils varied.

- Official Majority in Central Council: While it retained an official majority in the Central legislative council, the Act allowed provincial legislative councils to have a non-official majority. This was a notable departure from previous legislative councils where officials held the majority of seats.

- Enhanced Deliberative Functions: The Act expanded the deliberative functions of legislative councils at both the Central and provincial levels. Members were permitted to ask supplementary questions and move resolutions on budget matters, among other functions.

- Association of Indians with Executive Councils: For the first time, the Act provided for the association of Indians with the executive councils of the Viceroy and Governors. Satyendra Prasad Sinha became the first Indian to join the Viceroy’s executive council, serving as the Law Member.

- Communal Representation for Muslims: The Act introduced a system of communal representation for Muslims by accepting the concept of a ‘separate electorate.’ Under this system, Muslim members were to be elected exclusively by Muslim voters. This provision marked the formalization of communal representation and is associated with Lord Minto, who became known as the Father of Communal Electorate.

- Separate Representation for Other Groups: In addition to Muslim representation, the Act also provided for the separate representation of other groups, including presidency corporations, chambers of commerce, universities, and zamindars (landowners). This allowed these various segments of society to have a voice in legislative councils.

- The Indian Councils Act of 1909 introduced significant reforms aimed at increasing Indian participation in the legislative process and associating Indians with the executive councils. While these reforms represented a significant step forward in Indian political representation, they still fell short of providing full self-governance. The Act also formalized the concept of communal representation, which had lasting implications for Indian politics.

Government of India Act of 1919

- The Government of India Act of 1919, also known as the Montagu-Chelmsford Reforms, was a landmark piece of legislation passed by the British Parliament that introduced significant constitutional reforms in British India. It was named after Edwin Montagu, the Secretary of State for India, and Lord Chelmsford, the Viceroy of India. The key provisions and aspects of the Government of India Act of 1919:

- Demarcation of Central and Provincial Subjects: The Act relaxed central control over the provinces by separating central and provincial subjects. Central and provincial legislatures were authorized to make laws on their respective lists of subjects. However, the overall structure of government remained centralized and unitary.

- Introduction of Dyarchy: The provincial subjects were further divided into two categories: transferred and reserved. Transferred subjects were to be administered by the Governor with the aid of Ministers responsible to the legislative council. Reserved subjects were to be administered by the Governor and his executive council without being responsible to the legislative council. This system of governance was known as “dyarchy,” which means double rule. However, this experiment was largely considered unsuccessful.

|

- Bicameral Legislature: The Act introduced bicameralism in India for the first time. It replaced the Indian legislative council with a bicameral legislature consisting of an Upper House (Council of State) and a Lower House (Legislative Assembly). A majority of members in both houses were chosen by direct election.

- Representation in Viceroy’s Executive Council: The Act required that three of the six members of the Viceroy’s executive council (excluding the Commander-in-Chief) were to be Indian.

- Extension of Communal Representation: The Act extended the principle of communal representation by providing separate electorates for Sikhs, Indian Christians, Anglo-Indians, and Europeans. This allowed these communities to elect their own representatives.

- Limited Franchise: The Act granted voting rights to a limited number of people based on property ownership, tax payment, or educational qualifications.

- Establishment of High Commissioner for India: It created the office of the High Commissioner for India in London and transferred some functions that were previously performed by the Secretary of State for India to this new office.

- Central Public Service Commission: The Act provided for the establishment of a Central Public Service Commission in 1926. This commission was responsible for recruiting civil servants.

- Separation of Provincial Budgets: For the first time, the Act separated provincial budgets from the Central budget and authorized provincial legislatures to enact their own budgets.

- Statutory Commission: The Act included provisions for the appointment of a statutory commission to inquire into and report on its working after ten years of coming into force.

- The Government of India Act of 1919 introduced a range of reforms that aimed to increase Indian participation in governance, establish dyarchy in the provinces, and create a bicameral legislative system. While it represented a significant development in the constitutional evolution of India, it was still far from full self-governance, and its impact on Indian politics was complex.

Simon Commission

- Appointment of the Simon Commission: In November 1927, two years before the scheduled constitutional review, the British government announced the appointment of a seven-member statutory commission under the chairmanship of Sir John Simon. The commission’s purpose was to assess the situation in India under its new constitution. All members of the commission were British, which led to widespread dissatisfaction and boycott by Indian political parties because of the absence of Indian representation.

- Simon Commission’s Recommendations: The Simon Commission submitted its report in 1930. Among its key recommendations were:

- The abolition of dyarchy, which was the dual system of governance in the provinces.

- The extension of responsible government in the provinces, implying a greater degree of self-governance.

- The establishment of a federation of British India and princely states.

- The continuation of communal electorates, a practice that reserved seats for various religious communities.

- Round Table Conferences: To consider the Simon Commission’s proposals and other related issues, the British government convened three Round Table Conferences. These conferences brought together representatives from the British government, British India, and Indian princely states for discussions on constitutional reforms.

- White Paper on Constitutional Reforms: Based on the discussions at the Round Table Conferences, a “White Paper on Constitutional Reforms” was prepared. This document outlined the proposed constitutional changes for India.

- Joint Select Committee: The recommendations from the White Paper were submitted to the Joint Select Committee of the British Parliament for further consideration. This committee reviewed the proposals and made some modifications.

- Government of India Act of 1935: The final outcome of this process was the Government of India Act of 1935. This act implemented significant constitutional reforms, including the abolition of dyarchy, the introduction of provincial autonomy, and the establishment of a federal structure. However, communal representation and other aspects of the act remained contentious issues in Indian politics.

- The Simon Commission and the subsequent discussions and reforms marked an important phase in India’s journey towards self-governance. While it represented progress in some areas, it also highlighted the complexities and divisions within Indian society and politics, particularly regarding communal representation and minority rights.

Communal Award

- Communal Award (August 1932): Ramsay MacDonald, the British Prime Minister, announced the Communal Award in August 1932. This award was a scheme for the representation of various minorities in British India. It continued the practice of separate electorates for several communities, including Muslims, Sikhs, Indian Christians, Anglo-Indians, and Europeans.

- Extension to Depressed Classes: One significant aspect of the Communal Award was its extension of separate electorates to the “depressed classes,” which later came to be known as the Scheduled Castes. This move aimed to provide representation to the historically marginalized and disadvantaged communities within the Hindu fold.

- Gandhiji’s Opposition: Mahatma Gandhi was deeply troubled by the extension of the principle of communal representation to the depressed classes. He believed that it would further divide Indian society along communal lines and hinder the process of national unity. In protest, Gandhi undertook a fast unto death in Yerawada Jail in Poona.

- The Poona Pact: In response to Gandhi’s fast and the widespread concerns it generated, negotiations took place between leaders of the Indian National Congress and leaders representing the depressed classes, particularly Dr. B.R. Ambedkar. These negotiations resulted in an agreement known as the Poona Pact.

- Key Provisions of the Poona Pact: The Poona Pact retained the concept of a joint Hindu electorate, which was preferred by Gandhi and the Congress. However, it also addressed the concerns of the depressed classes by providing reserved seats for them within the general Hindu electorate. This arrangement aimed to ensure that the interests of the depressed classes were represented without creating a separate electorate for them.

- The Poona Pact represented a compromise between Gandhi and Ambedkar and prevented the further extension of separate electorates. It retained the unity of the Hindu community in electoral terms while providing for reserved seats to enhance the political representation of the depressed classes. This agreement helped maintain a more cohesive approach to political representation within the framework of communal politics in British India.

Government of India Act of 1935

- All-India Federation: The Act proposed the establishment of an All-India Federation, comprising both provinces and princely states as units. It divided powers between the central government and units through three lists: Federal List (for the Centre), Provincial List (for provinces), and Concurrent List (for both). Residuary powers were vested with the Viceroy. However, the federation never materialized due to princely states’ non-participation.

- Abolition of Dyarchy and Provincial Autonomy: Dyarchy in provinces was abolished, and “provincial autonomy” was introduced. Provinces were allowed to function autonomously within their defined spheres. Responsible government was established in provinces, where governors had to act on the advice of ministers accountable to the provincial legislature. This system was in effect from 1937 to 1939.

- Dyarchy at the Centre: The Act allowed for the adoption of dyarchy at the central level, dividing federal subjects into reserved and transferred subjects. However, this provision was not implemented.

- Bicameralism in Provinces: Six out of eleven provinces (Bengal, Bombay, Madras, Bihar, Assam, and the United Provinces) were made bicameral, with both a legislative council (upper house) and a legislative assembly (lower house). However, several restrictions were placed on these bodies.

- Extension of Communal Representation: The Act further extended the principle of communal representation by providing separate electorates for depressed classes (Scheduled Castes), women, and laborers.

- Abolition of the Council of India: The Act abolished the Council of India, established by the Government of India Act of 1858, and instead provided the Secretary of State for India with a team of advisors.

- Franchise Extension: The Act expanded the franchise, granting voting rights to about 10% of the total population.

- Establishment of the Reserve Bank of India: The Act paved the way for the creation of the Reserve Bank of India, responsible for controlling the country’s currency and credit.

- Public Service Commissions: It provided for the establishment of not only a Federal Public Service Commission but also Provincial Public Service Commissions and Joint Public Service Commissions for two or more provinces.

- Federal Court: The Act provided for the establishment of a Federal Court, which was established in 1937.

- The Government of India Act of 1935 introduced significant changes to the governance structure of British India, focusing on provincial autonomy and the potential for a federal system, although the latter did not fully materialize. It played a role in shaping the political landscape of India during the lead-up to independence.

Indian Independence Act of 1947

- British Prime Minister Clement Atlee announced that British rule in India would end by June 30, 1948, and power would be transferred to responsible Indian hands. This announcement set the stage for India’s independence. Following Atlee’s announcement, the Muslim League, led by Muhammad Ali Jinnah, intensified its demand for the partition of India to create a separate Muslim-majority state, Pakistan. On June 3, 1947, Lord Louis Mountbatten, the Viceroy of India, presented the Mountbatten Plan. This plan proposed the partition of India into two independent dominions, India and Pakistan, with the right to secede from the British Commonwealth. Both the Indian National Congress and the Muslim League accepted this plan.

- The Indian Independence Act of 1947 was enacted to implement the Mountbatten Plan. Its key features were as follows:

- It declared India as an independent and sovereign state from August 15, 1947.

- It provided for the partition of India into two independent dominions, India and Pakistan.

- It abolished the office of Viceroy and established the position of Governor-General for each dominion, to be appointed by the British King on the advice of the dominion’s cabinet.

- It empowered the Constituent Assemblies of both dominions to draft and adopt their respective constitutions and repeal any British Parliament acts, including the Independence Act.

- It allowed both dominions to legislate for their territories until new constitutions were enacted, and no British Parliament acts passed after August 15, 1947, were to extend to either dominion unless adopted by their legislatures.

- It proclaimed the end of British paramountcy over Indian princely states and treaty relations with tribal areas.

- It granted princely states the choice to join India, Pakistan, or remain independent.

- It provided for the governance of each dominion and province by the Government of India Act of 1935 until new constitutions were adopted, with the authority to make modifications.

- It eliminated the British Monarch’s right to veto bills or request bill reservations but retained this right for the Governor-General.

- It designated the Governor-General and provincial governors as constitutional (nominal) heads, acting on the advice of their respective councils of ministers.

- It removed the title of Emperor of India from the King of England’s royal titles.

- It discontinued the appointment and reservation of posts by the Secretary of State for India.

- Midnight of August 14-15, 1947: At midnight on August 14-15, 1947, British rule officially ended, and India and Pakistan became independent dominions. Lord Mountbatten became the first Governor-General of India, and Jawaharlal Nehru was sworn in as the first Prime Minister of independent India. The Constituent Assembly of India, formed in 1946, became the new nation’s Parliament.

- These historic events marked the culmination of India’s struggle for independence from British colonial rule and the beginning of a new era as independent nations.

Interim Government (1946)

- The Interim Government was formed on September 2, 1946, and it lasted until August 15, 1947, when India gained independence from British rule. The Interim Government was a coalition government that included members of the Indian National Congress (INC) and the Muslim League. The INC was the largest political party in India, and it was led by Jawaharlal Nehru and Vallabhbhai Patel. The Muslim League was the second largest political party in India, and it was led by Muhammad Ali Jinnah.

- The Interim Government was responsible for overseeing the transition of India to independence. It also played a role in negotiating the terms of the partition of India into two separate countries: India and Pakistan.

| Member | Portfolio |

| Jawaharlal Nehru | Vice President, External Affairs and Commonwealth Relations |

| Vallabhbhai Patel | Home, Information and Broadcasting |

| Rajendra Prasad | Food and Agriculture |

| C. Rajagopalachari | Education and Arts |

| C.H. Bhabha | Works, Mines and Power |

| Asaf Ali | Railways and Transport |

| Jagjivan Ram | Labour |

| Baldev Singh | Defence |

| Liaquat Ali Khan | Finance |

| Ibrahim Ismail Chundrigar | Commerce |

| Abdur Rab Nishtar | Communications and Posts |

| Ghazanfar Ali Khan | Health |

| Jogendra Nath Mandal | Law |

First Cabinet of Free India (1947)

| Members | Portfolios Held |

| Jawaharlal Nehru | Prime Minister; External Affairs & Commonwealth Relations; Scientific Research |

| Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel | Home, Information & Broadcasting; States |

| Dr. Rajendra Prasad | Food & Agriculture |

| Maulana Abul Kalam Azad | Education |

| Dr. John Mathai | Railways & Transport |

| R.K. Shanmugham Chetty | Finance |

| Dr. B.R. Ambedkar | Law |

| Jagjivan Ram | Labour |

| Sardar Baldev Singh | Defence |

| Raj Kumari Amrit Kaur | Health |

| C.H. Bhabha | Commerce |

| Rafi Ahmed Kidwai | Communication |

| Dr. Shayama Prasad Mukherji | Industries & Supplies |

| V.N. Gadgil | Works, Mines & Power |

UPSC PREVIOUS YEAR QUESTIONS

1. In the Government of India Act 1919, the functions of Provincial Government were divided into “Reserved” and “Transferred” subjects. Which of the following were treated as “Reserved” subjects? (2022)

1. Administration of Justice

2. Local Self-Government

3. Land Revenue

4. Police

Select the correct answer using the code given below:

(a) 1, 2 and 3

(b) 2, 3 and 4

(c) 1, 3 and 4

(d) 1, 2 and 4

2. The distribution of powers between the Centre and the States in the Indian Constitution is based on the scheme provided in the: (2012)

(a) Morley-Minto Reforms, 1909

(b) Montagu-Chelmsford Act, 1919

(c) Government of India Act, 1935

(d) Indian Independence Act, 1947